Top 10 JAMnews articles from Azerbaijan in 2023

Best articles of 2023

We have collected the “top ten” of the best, in our opinion, materials of JAMnews Azerbaijani editorial staff published in 2023.

We offer them to your attention.

The main religious administration of Azerbaijani Muslims (according to some) is the Caucasian Muslim Board. For many years all mosques in the country were under the control of this body.

“Azerbaijan was influenced by long years of living under the Soviet regime with its atheistic thinking. And religion here does not particularly affect society, although in recent decades this has been changing,” theologian Elshad Miri says.

“Religion has a much greater influence in the south of the country, which is associated with the close proximity of this region to Iran. The same situation develops in separate quarters or settlements where believers live in density. Among the suburban settlements of Baku, Nardaran stands out in this respect.”

But in general, Miri says, one can hardly talk about the great role of religion in the politics and social life of Azerbaijan.

The village of Balik in the Ismayilli region is located 50 kilometers from the regional center. According to the latest census, the population of the village is 400 people.

According to dictionaries, the name of the village means “favorite place”. But for local residents, it is “a village erased from the map”, “a nowhere village of the district”, or simply a “swamp”.

Walking around the village you see fallen power lines. According to residents, they have repeatedly contacted the chief engineer of the district to help get them back up, but so far there’s been no activity.

“The poles have all fallen. We complain, no one bothers. Like you’re talking to a rock,” says Sahib Kamalov, a resident.

He was born in Balik. He says nobody is interested in them, so the village is basically ruined. The young are almost all gone – no education, no jobs around.

Two wars for one life

Khalisa Mammadova lived through both Karabakh wars. In the first war she was forced to leave her native village as a child, and in the second she lost her husband three months after their wedding.

“Although we were close, I never saw him. But he remembered me. In 2009, a close relative of ours came to ask after me for Amil. Without even thinking, without any reason, I refused. But apparently fate wanted it another way, and we met eleven years later, in 2020, when one day I was returning home from work.

To be honest, I don’t remember that moment. But Amil said: “You didn’t even raise your head to look in my direction.” He said that at that moment he decided that I would become the love of his life. He said that he was afraid that I would not like it. “I thought that I was an ordinary soldier, and you are a girl with a higher education, a little smug, maybe you won’t even say hello to me,” Amil said.

He confessed to me, so I decided to give him a chance. He said: “When you said that you agreed to get to know me better, the whole world became mine. And when I see you next to me now, I can’t believe my eyes.”

“After we got married, we started buying new things for our house. Amil really liked the carpet for the living room. He said, let’s put the table so that the light falls on the carpet and its color can be seen better. But in the end his body was wrapped, according to custom, in the same carpet. All the villagers, everyone who was at the funeral, saw the carpet that he loved so much.”

Dilber Ahadzade sent her two sons to the second Karabakh war in 2020. One of them did not return. Having moved to Baku from the country and not having her own housing, for many years Dilber lived in an abandoned dormitory —- two rooms in substandard condition, and there she raised her sons.

After the death of her eldest, the state allocated her a bright, new, two-room apartment. Every corner of this apartment, from the very doorway, she decorated with photographs and other reminders of Elsever. Her only consolation now is her son Farid, who was wounded in the war and her husband, who suffered a stroke long before the war, and whom she hopes will one day recover.

On the morning of September 21 the military commissariat called”, Dilber says. “Elsever was at work, they called his father. I took the phone. They told Elsever to report immediately to the Commissariat. That evening, Elsever waited a little for his brother to say goodbye to him. He loved him very much. But Farid was late from work, Elsever was already late, couldn’t wait any longer and left.”

Dilber sobs and immediately asks her younger son to come out.

She rubs palms together, wipes away tears, straightens up.

“I can’t cry in front of him. And he doesn’t cry with me. Two years have passed, but it seems to me that everything just happened yesterday. Elsever was taken away on the pretext of military training. Elsever spent a week in Baku, then he was sent to the front. Farid was taken away the same week, on the 29th. I saw Farid off myself.”

In one Baku district, known as “Kubinka”, there is a “tinkerers’ quarter”. The first tinsmiths appeared here in the ’60s and now you can find several tin workshops there.

The roots of tinsmithing go back to the village of Lagich, Ismayilli region. Those who moved from there to Baku continued their craft in the capital.

Due to the lack of customers during the day, one of the masters spends time waiting reading books, another solves crossword puzzles, and they talk with friends.

Compared to the past, tinsmiths have fewer customers. They say the reason for this is that younger people prefer modern, lighter objects. Zahid Eyvazov says that earlier, in the dowry of girls getting married, there was always copper utensils. Now there is no such need, which affects the earnings of copper workers.

Finally, we get to Griz, but Farhad had to tell me this. I’m not used to seeing such a village. There are only steep rocks around, old tombstones that have sunk into the ground. No people, trees or plants around; there is nothing for the latter to grow on.

According to local residents, graves are dug where it is still possible to dig somehow. Digging a grave in Griz is the hard work that all the men of the village do for many hours. It is said that once they had to dig a grave for three days.

This story is about the volunteer teaching activities of journalist Joshgun Eldaroglu in a remote village in Azerbaijan.

For about two years now, he has been traveling to the village of Gazbabaly in the Shabran region, where he teaches the Azerbaijani language, mathematics, and English.

I come from the Shabran region. I used to go there occasionally. One day I went to visit relatives. There I was introduced to a little girl named Nazrin. I was surprised by her story. She said that she would not go to school this year. After asking the reason, I found out that in their village, the school provides education only up to the fourth grade. I also learned that there are other children in this village, like Nazrin, who will not be able to continue their education. Although these children want to learn, they do not have the opportunity.

Teresa Hamlin is an English teacher who came to Azerbaijan eighteen years ago. In the early years she taught English, but later her interest in the Azerbaijani people, traditions and culture led her in a different direction. Unemployment among Azerbaijani women gave Teresa an idea for social entrepreneurship.

The goal of the project is to bring together unemployed women living in the regions of Azerbaijan who have knitting skills to produce and sell woolen products.

Teresa buys various types of thread and leather fabric for the soles of woolen socks, then distributes them to women in the districts, who in turn knit different products.

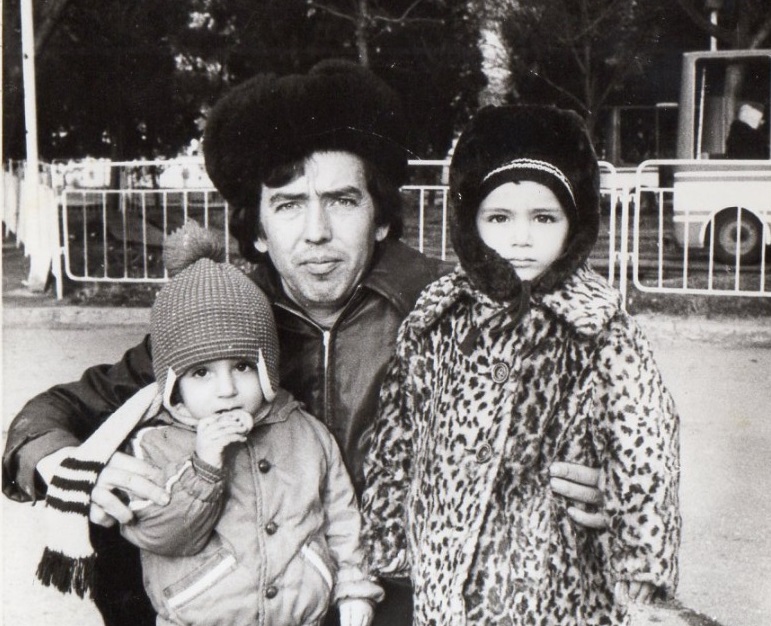

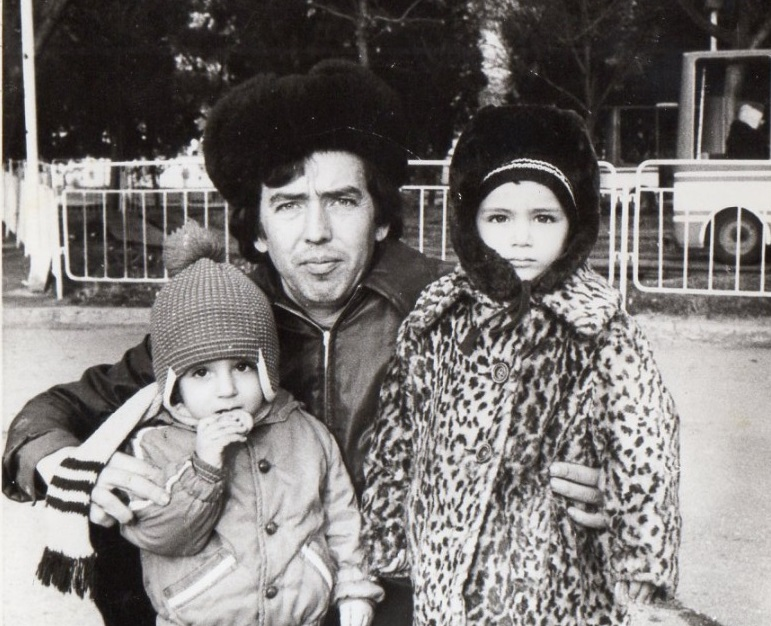

“There are no photos where dad and mom are together. They collected photos in one album. When we moved, our things were moved to my grandmother’s house, and then there was a fire and the album was destroyed.

“Pictures” of Emil’s mother and father together remained only in his memory. Emil Rahimov, 42, was born in Baku. His father is Armenian, his mother Azerbaijani. They fell in love as students and got married, then had two boys. This was in the ’80s, when the two peoples lived in peace.

“I’ve been hit by a car three times. Yesterday it hit me and drove off. It was four o’clock in the morning. Accidents are more common at that time. When it’s dark, the street lights are off. The car hit me and drove on. I couldn’t even see what kind of car it was. I was lucky I wasn’t seriously injured. My back was a little sore, but today it’s better, so I went to work.”

Nabat Maharramova is 63 years old. For the last 21 years she has been working as a cleaner on the central streets of Baku. Nabat goes out every morning at four o’clock at dawn to sweep the roads where cars drive. She says it is dangerous to work on the highway, but she has no other means. Although it is dangerous, she is glad that she has at least some work.

Nabat says that after the first two accidents she went to the police, but the drivers who hit her were not found. The last time she did not even complain. Although all three accidents occurred during work, the employer was not held responsible. She paid for her own medical treatment each time.