Tbilisi, Bolnisi, Washington, Kobuleti – how coronavirus has changed daily life

Georgian citizens living around the world tell JAMnews about their experiences of the pandemic

Mariko Tsikoridze, Bolnisi (Georgia), journalist

“When the Georgian prime minister announced late at night on March 22 that Bolnisi — the city where I live — was a “red zone,” I was in complete shock.

I stepped outside and saw all the other perplexed faces. Somehow, people had already got outside to start queuing. The bakeries quickly ran out of bread, and in the grocery stores, people bought pasta and sugar by the sack. The pharmacies had no masks, gloves or antiseptics.

Everything changed. We stopped talking to one another — we even stopped going to friends’ houses for a cup of coffee.

By the evening, the city was a ghost town.

The worst part about it is the realization that this is just the beginning, and no one knows when it will end.”

- Georgia: Marneuli and Bolnisi brace for epidemic – what’s happening in the city on lockdown. PHOTOS

- “We’re afraid of losing our jobs” – Georgian city Akhalkalaki hunkers down for COVID-19

Jemal Khutsishvili, 79, Tbilisi, taxi driver

“I see the signs of panic. Especially among people my age, because the virus is particularly unforgiving to the elderly population.

I’m keeping safe by practicing good hygiene – my hands already hurt from how much I wash them. And I’ll have a little vodka after work, for good measure.

I live with my daughter. She works in a store, and the retailers are frightened, with talks of impending shortages. So we’ve stocked up and have a reserve at home.

There have been a lot of changes, and at least one of them is good — there are no lines to get retirement checks.”

Nana Sajaia, Washington, journalist

“I’m a producer for Fox News, and I have journalists reporting from Rome, New York, Seattle—even from their own kitchens.

Fox News has not fully switched over to working remotely. The essential employees we can’t live without still go into the office.

Yesterday it was my turn. Everyone in the office observed strict social distancing rules all day.

My experience living in Tbilisi in the 90s taught me well, so I stocked up on groceries and medicine. I try not to touch anything directly, even elevator buttons.

But my discomfort is just a drop in the ocean. There are issues that people aren’t talking about. For instance, in the USA, there are 20 million children on the free school lunch program. Now the schools are closed. How are they getting fed?

27 million Americans don’t have health insurance. 82 million are paid by the hour, and now they have been left without work. How are they going to survive?

Kravai Tkemaladze, 26, Tbilisi, bartender

“I had just picked myself up again when the coronavirus kicked me back down. Now there’s no work, and no one knows when there will be again.

The uncertainty of it all keeps me up at night.

There’s a “social virus” that’s even more infectious than the coronavirus, which can be avoided with proper hygiene. And all this right when you start to become interested in life and learning…but instead, there is only chaos.”

Nora, 93, Kobuleti, village of Mukhaestate (Georgia), retiree

“I have a hazelnut and citrus grove, and I also grow flowers, kiwis and bananas.

Usually, I spend the winter in Tbilisi with my relatives, and then return around Easter. But as soon as I heard about the virus, I came back home.

They say the virus does not spare the elderly. I take Vitamin C for protection and recommend everyone else do so, too.”

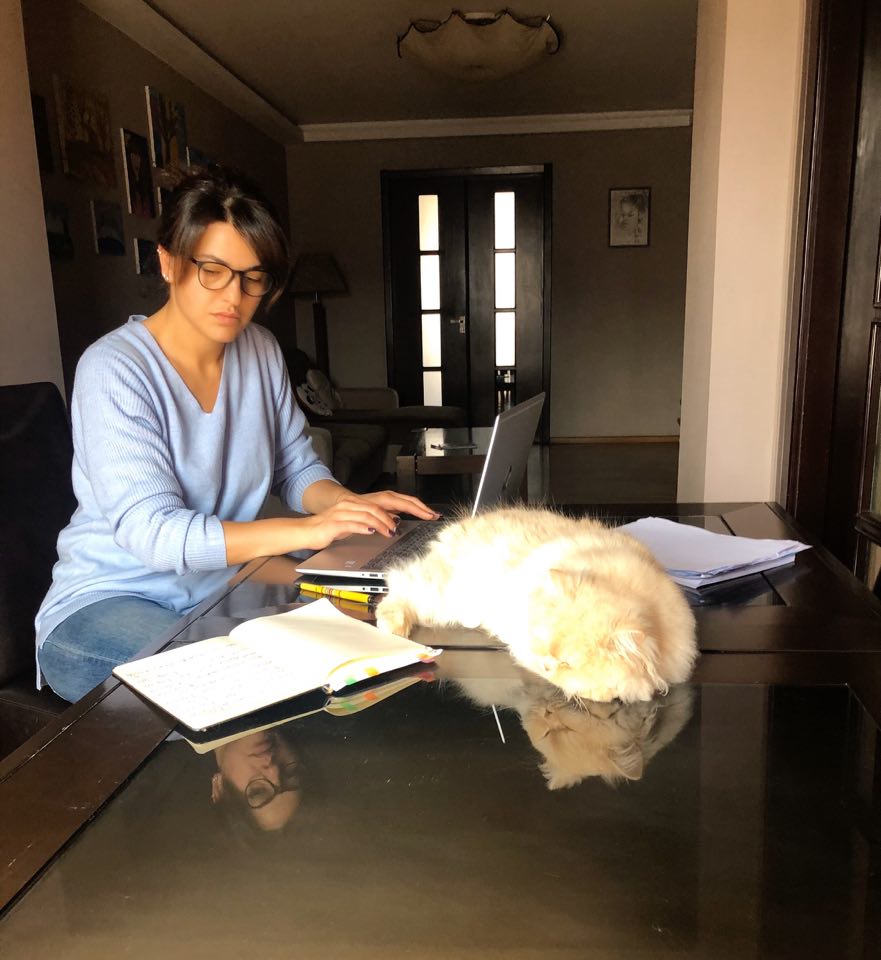

Shorena Onashvili, Tbilisi, HR manager

“I was delighted to hear we were going to start working remotely: I wouldn’t have to rush to work in the morning and crawl back, half dead from exhaustion, at night.

I started my first day of working from home in good spirits. All I had to do was turn on my computer, and we were off and running! And when my daughter woke up, I dressed and fed her.

But then, I had to run around, making dolma and writing business emails at the same time.

Now I only want one thing — for things to go back to normal.”