How Abkhazia is trying to restore its historic archive which burned down 27 years ago during the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict

The process of restoring files of the national archive of Abkhazia, which burned to the ground on the night of October 22, 1992 during the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, has picked up speed.

On both sides of the conflict, many believe that the building was then deliberately set on fire by the Georgian military. Although on the Georgian side, there are many who refute this. One way or another, this tragedy affected the whole of Abkhaz society, and to this day, many there speak of a keen sense of loss.

What happened then, what has been preserved or can be restored, and how international experts, as well as Georgian scientists, are helping in the process: below, a report from the archive storage in Sukhum.

Archives in the South Caucasus existed and worked as important scientific institutions both before and during the Soviet era. But the end of the Soviet Union gave societies new goals, and archives became an important tool for them in substantiating their history and prospects of statehood.

This was no less true for the archive in Abkhazia as well.

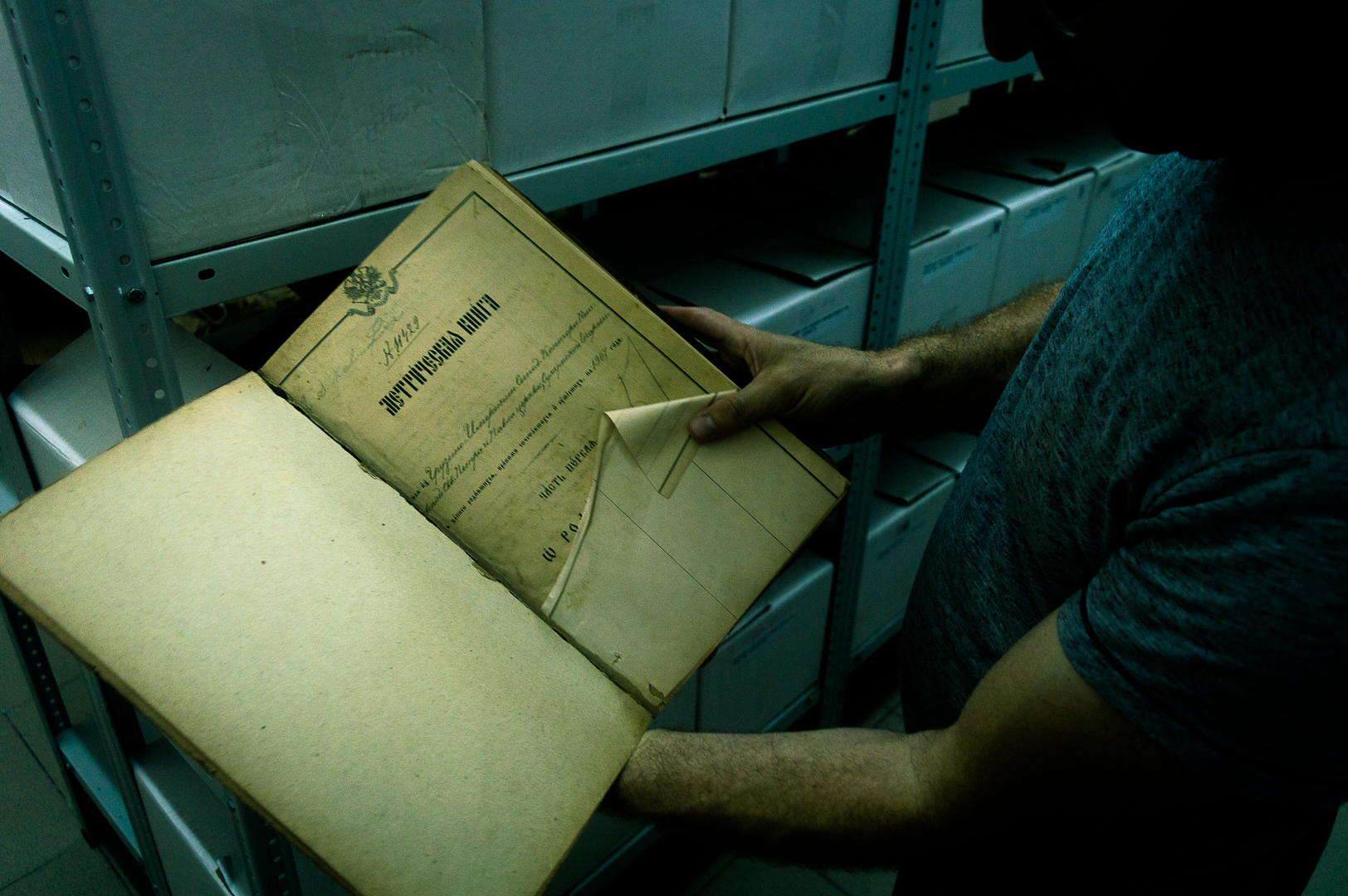

“Once the archive in Sukhum contained more than 176,000 artifacts sorted by 693 funds. These were thousands of heavy books, folklore records, photographs. The oldest copy dates back to 1810. The collection of documents of the 19th century was completely unique,” says archivist Dmitry Enik.

But on August 14, 1992, the armed conflict began in Abkhazia.

It lasted 13 months and ended on September 27, 1993 with the defeat of the Georgian armed forces. According to unverified data, more than 13,000 people lost their lives on both sides, more than a thousand went missing, according to various sources, and about 300,000 people became internally displaced persons, the vast majority of them were Georgians.

And another victim was the National Archives of Abkhazia.

•Everything on the Georgian-Abkhaz Conflict

How the Abkhaz archive was destroyed

The Georgian military entered Sukhumi, the capital of Abkhazia, five days after the outbreak of hostilities. The city then remained under the control of the Georgian side for more than a year. After the fighting on September 27, 1993, the Abkhaz military, supported by forces from the republics of the North Caucasus, took the city.

The archive building was burned in October 1992. The Abkhaz public today is unanimous in the assertion that the Georgian military intentionally set fire to the archive in order to destroy evidence of the history of the Abkhaz people.

•Photo archive: Georgian families leaving Abkhazia during the 92-93 Georgian-Abkhaz war

•Zakareishvili: “Sooner or later the authorities will have to consider my ideas”

•Op-ed: the Georgian-Abkhaz dead-end

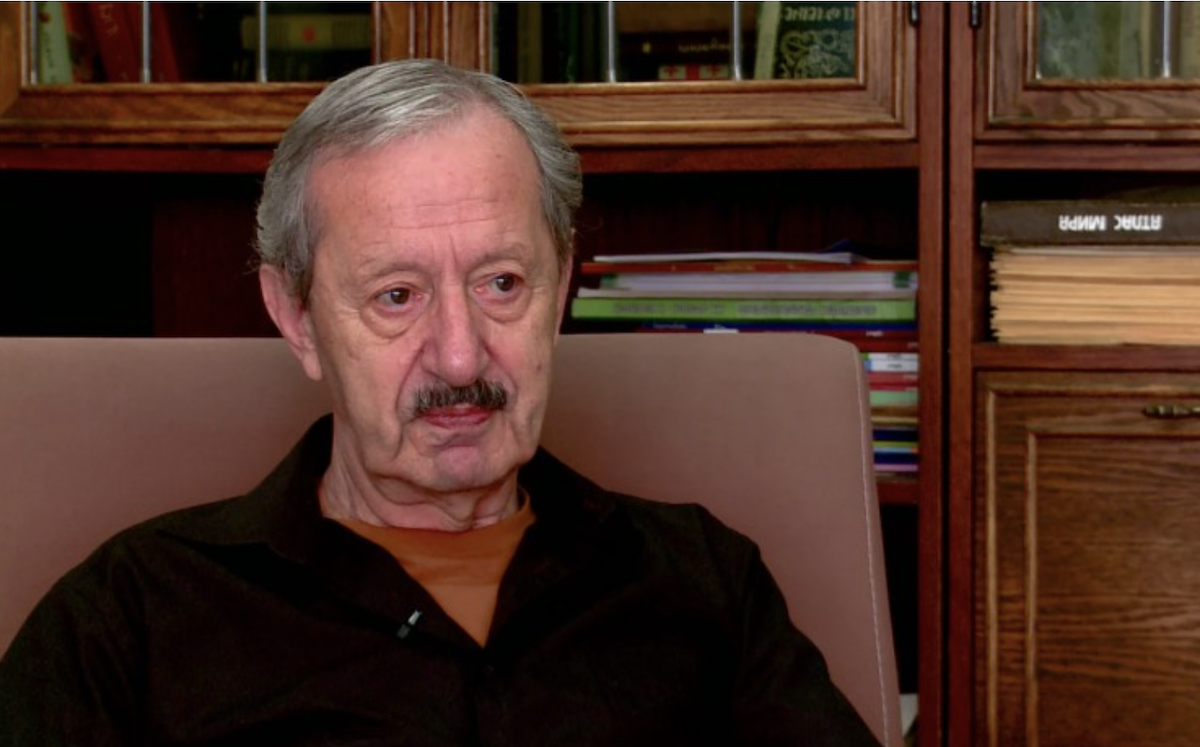

“There is reason to blame the Georgian military for destroying the Abkhaz archive. However, this story has grown into so many diverse, unverified stories that it has become a kind of historical legend in Abkhazia,” said Paata Zakareishvili, a political scientist and former Minister for Reconciliation and Civil Equality.

Today at the site of the archive

Today, on the site of the archive in Sukhum/i, there are no reminders about its existence. There is a small field, green in summer, gray-yellow in winter. The coast is very close, so when you stand on the spot it smells of the sea.

“Recently, we created a historical exhibition on Lake Ritsa. I really wanted to tell the story of these places, based on documents. But there are no documents.

“All we can do is rely on oral stories that have been passed down from generation to generation, and old photographs that have been preserved in some families,” says Taisiya Alania, who works at the Abkhaz State Museum in Sukhum/i.

The other side of the problem is the thousands of burnt personal documents: birth, death, pension certificates and so on.

“Theoretically, there is a way out for them,” says Taisiya Alania. “Many documents from the Abkhaz archive were copied into the republican archive in Tbilisi. As well as many historical documents of Georgia were copied to the archives in Moscow or St. Petersburg.”

But this is only a theoretical possibility; the Abkhaz have no practical access to these documents since the conflict of the 1990s.

Cooperation with Georgian specialists

To restore their documents, a resident of Abkhazia must go to Tbilisi. Theoretically, there are no barriers to this. The Georgian side in every possible way welcomes the arrival of residents of Abkhazia in Tbilisi and other cities of Georgia, and it is very simple and easy to cross the Inguri bridge and find yourself on the Georgian side.

However, in the conditions of the unresolved conflict, this opportunity seems very difficult to fulfill for most residents of Abkhazia.

A lot of people come from Abkhazia to Tbilisi for treatment. Georgia has a high level of medicine, and there is also a special preferential program for residents of Abkhazia – almost all medical procedures and hospital stays are free for them.

But those who come hide that they do so. Attitudes towards visits to Georgia in Abkhazia are extremely negative.

•VIDEO: Abandoned Georgian villages in Abkhazia

“I have repeatedly helped people from Abkhazia get their documents from the Tbilisi archive,” says Georgian historian Gia Anchabadze. “Although it’s often difficult to find them.”

Gia Anchabadze is respected both in Georgian society and in Abkhazia, and gives lectures in Tbilisi and Sukhumi.

He was one of the first who began to help with the restoration of the burned Abkhaz archive and the transfer from the Georgian archives of copies of documents of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Then other Georgian specialists joined this project.

“I have repeatedly helped people from Abkhazia get their documents from the Tbilisi archive,” says Georgian historian Gia Anchabadze. “Although it’s often difficult to find them.”

Gia Anchabadze is respected both in Georgian society and in Abkhazia, and gives lectures in Tbilisi and Sukhumi.

He was one of the first who began to help with the restoration of the burned Abkhaz archive and the transfer from the Georgian archives of copies of documents of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Then other Georgian specialists joined this project.

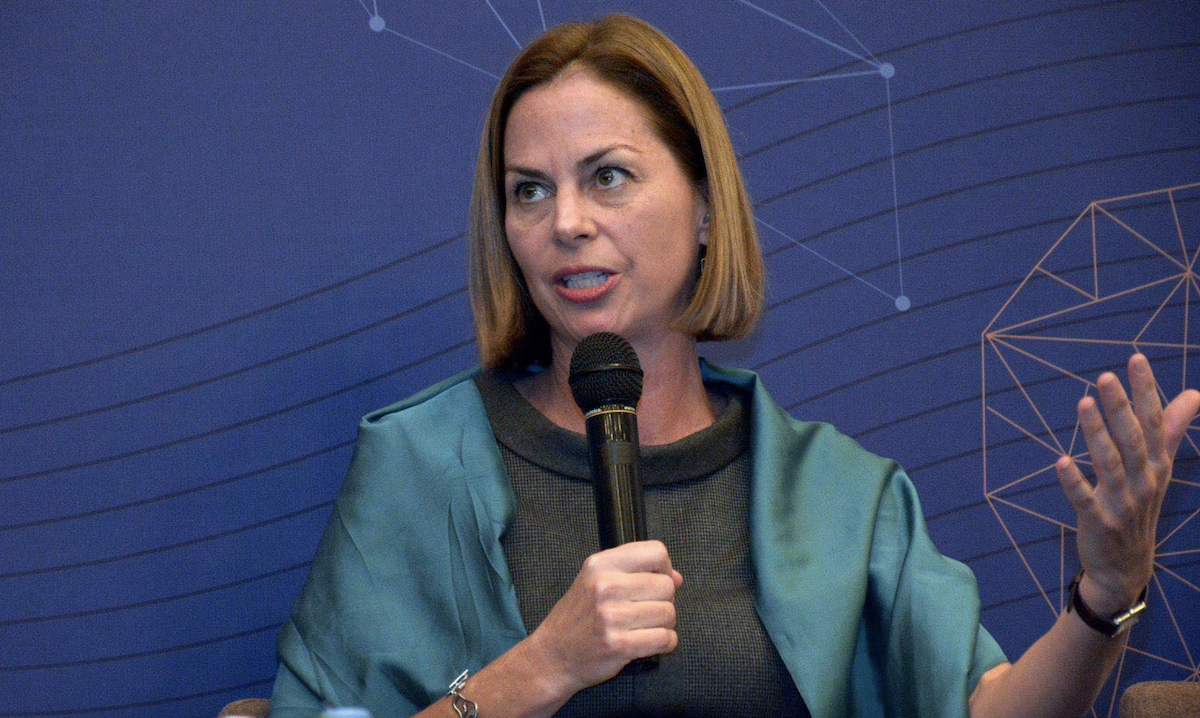

“This is not very widely known in Abkhazia, but as part of the Georgian-Abkhaz civil dialogue, we handed over to the Abkhaz side many archaeological documents, as well as ancient maps of Sukhumi. Although it can be difficult to agree even on non-political issues on which there are documents in the Georgian archives,” says Marina Elbakidze, project manager at the Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development (Tbilisi).

Irakli Khvadagiani, an employee of the Tbilisi Laboratory for the Study of the Soviet Past, has extensive experience in collecting historical documents. He considers the main problem the high cost and complexity of access to the Georgian archives.

“We use mainly family archives. Access to the state archives requires a lot of money; copying documents is incredibly expensive there. And to some documents we do not have access at all.”

Help from Western organizations

During the fire that destroyed the Abkhaz archive in 1992, those who ran first were able to save two boxes of copies of documents from the fire.

They were later re-photographed, but they were not able to investigate them for a long time.

“These negatives are very old, it’s very difficult and expensive to get information from them,” say Czech archivists who participated in the project for the restoration of photographic materials.

International specialists have helped out with restoring the documents and obtaining them from Tbilisi under a EU-supported project launched in 2018.

The Czech Development Agency was actively engaged in the effort.

Archive Deputy Director Dmitry Enik showed how the restoration process went. Careful cleaning, formatting, computer processing, printing – and the documents are sent for storage.

About five thousand pages have been restored. This allowed archivists in Abkhazia to create as many as two new storage sections.

But there is still a lot of work ahead, since thousands of pages of documents continue to remain in the form of negatives and await thorough processing and study.