Repatriation in Abkhazia: myths, expectations and reality

Mukhajirs in Abkhazia and repatriation

The programme for the repatriation of the descendants of the Muhajirs – thousands of families of Abkhazians, Circassians expelled from their homeland in the 19th century when the Russian Empire conquered the Caucasus – faces a number of problems in Abkhazia.

It is estimated that 80 percent of all ethnic Abkhaz in the world live outside their historic homeland.

How many there are exactly nobody can say – the numbers range from 500,000 to a million people.

A few years ago, the proposition of organizing a global census of Abkhaz was floated.

The representative of Abkhazia in Germany, Hibla Amichba, made such a project in 2015, and the republic’s leadership supported this idea. But it never came to implementation.

The largest Abkhaz diasporas are in Turkey, Syria and Jordan. In the days of Tsarist and then Soviet Russia, they were forbidden from entering their homeland.

But in the past 25 years, Abkhazia has officially announced repatriation a ‘cherished dream of the people’ and ‘national idea’.

Who is returning home to Abkhazia after a century and a half and why? How are they met, and what awaits this new diaspora in the future?

How Russia conquered the Caucasus

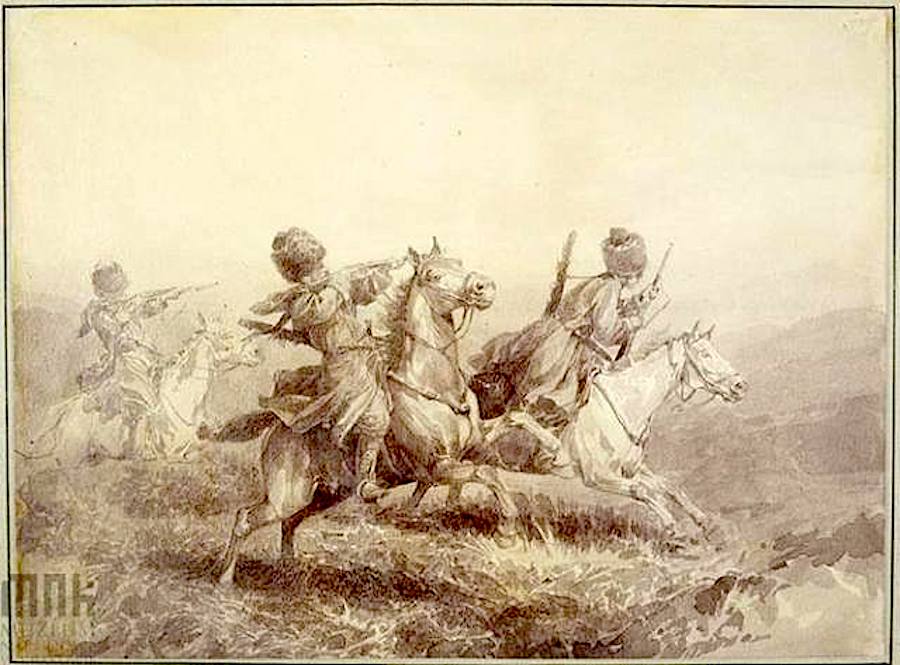

The Abkhaz diaspora in the Middle East was formed in the 19th century, when as a result of the Russian-Caucasian Wars, a number of Abkhaz, Circassians and other local peoples became muhajirs and were forced to leave the area.

The long and bloody conquest of the North Caucasus by the Russian Empire was long and bloody, lasting from 1817 to 1864.

Alexander Fonville, a French military observer in the Caucasus Army, says (from the book “The Last Year of the Circassian War of Independence, 1863-1864”):

From all the places successively occupied by Russians, the inhabitants of the auls [villages] fled, and their hungry parties crossed the country in different directions, scattering the sick and dying in their paths; sometimes whole crowds of immigrants froze or drifted with snowstorms, and we often noticed, passing, their bloody tracks. Wolves and bears raked at the snow and dug out human corpses from under it.”

Another historian of the Caucasian wars, Adolf Berger, writes in his book “Eviction of Highlanders from the Caucasus”:

“We could not retreat from the business we had begun just because the Circassians did not want to submit. It was necessary to exterminate the Circassians in half to force the other half to lay down their arms. The plan proposed by Count Evdokimov for the irrevocable end of the Caucasian Wars by the destruction of the enemy is remarkable for its deep political thought and practical fidelity.”

The process of expelling the local population to Turkey and the countries of the Middle East was called the Mahajirstvo. As a result of forced resettlement, including 3/4 of the territory of Abkhazia.

Today’s international Abkhaz diaspora are the descendants of those muhajirs.

Far fewer repatriates than expected

The repatriation committee, called to establish relations with foreign Abkhaz diasporas, was created in Abkhazia in March 1993, at the height of the Georgian-Abkhaz war. Abkhazia needed the support of the diaspora.

Five years later, in 1998, an extra-budgetary fund was created in Abkhazia to finance the repatriation programme.

Its budget is formed at the expense of two percent of the salaries of all living in Abkhazia. It is expected that in 2020 it amounted to 156,246,000 rubles [approximately $2.5 million].

In the reunification of Abkhaz separated from the republic, the committee sees not only an issue of addressing historical injustice, but also the solution of the demographic problems of the small nation.

This subsequently affected the name of the structure. At first, the committee was transformed into a ministry, and in November 2019 it was renamed the Ministry of Demography and Repatriation.

At the same time, there are quite a few questions for this ministry.

•The main one: why has a state programme for repatriation not been adopted and presented to the public?

•Another important question: why in 25 years have only about 10,000 people received the status of a repatriate? Moreover, only half of them permanently reside in Abkhazia.

Reasons for moving: homeland, apartment, avoiding prison

“You should not compare Abkhaz repatriation with Israeli or Greek,” says Omer Agrba.

Omer first came to Abkhazia in 1992 during the Georgian-Abkhaz war, he fought on the Abkhaz side among the volunteers from Turkey.

After the war, he stayed to live in Sukhum.

“The Greeks, of whom there were once were many in Abkhazia, almost all left for their homeland. Greece and Israel itself are more prosperous countries with good medicine and, probably, a social welfare programme. Therefore, their repatriation is successful.

Abkhazia can hardly be called prosperous. There is still devastation here, people dream of normal sidewalks and an uninterrupted supply of light and water. People come here not for a better life, but rather out of patriotic feelings,” he said.

Active campaigning is going on among the Abkhaz in Turkey – to return to their homeland, Omer says.

The status of repatriate for Abkhaz and Abazins who have come for permanent residence is valid for five years. All this time they are given financial assistance, provided with land and housing.

For many, this is what becomes a decisive factor.

“Each repatriate has a story. Some really have nothing to lose in Turkey – they cannot find a paid job, pay high taxes. And here they are promised to be give an apartment or land. So they decide to move. If it doesn’t work out – you can always go back.

“But there are those who sell all their property in Turkey to move here with the whole family and open their own small business. This needs guarantees, security, they want to be sure that no one will come to squeeze their business and leave them with nothing.

And in Abkhazia no one can give such guarantees,” Omer says.

Among the repatriates in Abkhazia there is a small group of people who are hiding from justice. Among them are criminals convicted of murder and escaped from prisons in Turkey. According to unofficial information, there are about fifteen such people in Abkhazia.

What happened to the families that got to Turkey and the Balkan countries?

The great-great-grandfather of Omera left for Turkey in 1864, in the year of the end of the Russian-Caucasian war, which ended in a victory for Russia.

At first, like some of the other immigrants from Abkhazia, the maternal ancestors of Omer settled in the Balkans, on the territory of modern Bulgaria, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Later, with the beginning of the Balkan wars, when the peninsula separated from Turkey, the settlers were forced to flee fighting for a second time.

“War, poverty, hunger are not the only troubles that fell on my family’s head at the beginning of the 20th century. Immigrants were plagued by epidemics. In one year, my grandfather and grandmother lost four sons. Then a few years later, when they settled in the north-east of Anatolia, four more children were born to them. Among them is my mother,” said Omer.

[su_pullquote]From 1993 to 2018, more than 10,000 repatriates arrived in Abkhazia, about half of them remained there to live[/su_pullquote]

Omer says his parents always talked about Abkhazia as a kind of promised land and dreamed of seeing it someday. But their son’s decision to go to Abkhazia to the war in the 1990s was met without enthusiasm.

“They didn’t just dissuade me – they stole and hid my passport. My parents returned the documents when they realized that I was adamant. But the fact that I would stay in Abkhazia after the war, they immediately understood and accepted.

“Now there is the Internet, we are always in touch with relatives. And before, to call from Sukhum to Adapazar (a city in the north-east of Turkey) it was necessary first to get a connection with Sochi, then with Moscow, Moscow with Istanbul, and from there with Adapazar. And at the same time, someone must have been at home to pick up the phone,” says Omer.

At the same time, he says, traveling from Turkey to Abkhazia and vice versa in the 1990s was much easier than now. Then it was possible to reach by sea. Now this is no longer possible. Flying from Sochi is expensive and inconvenient due to the need to apply for a Russian visa for Turkish citizens.

The cheapest option, according to Omer, is to arrive by car through Batumi, through Georgia. But then every time you need to get permission from the Abkhaz Foreign Ministry to enter Abkhazia.

An apartment in Abkhazia – not for sale, exchange or event rent

The main share of the repatriation fund budget is spent every year on the construction and purchase of housing for repatriates.

The keys to new apartments in 2019 were received by 48 families of returnees. Housing is under construction for another 96 families of returnees.

[su_pullquote]2018 was a record year in repatriation statistics: 543 Abkhaz resettled from Syria, Turkey, Jordan, Russia, Egypt, the USA, the Netherlands, Lebanon, one each from Estonia, Georgia and Israel

[/su_pullquote]For those who are still waiting for an apartment, the ministry pays rent.

These privileges regularly provoke disagreements between repatriates and local residents, as the housing issue is very acute in Abkhazia.

Many are outraged that such support is not being provided to young and large families, which would also help the demographic issue in the republic.

At the same time, apartments provided to repatriates do not actually belong to them.

These apartments cannot be sold, exchanged or even rented out. Repatriates live there on the basis of an agreement in which all these conditions are prescribed. A house or apartment can be redeemed only after the family has lived there for ten or more years.

Most of the repatriates live in Gulrypsh district, in the village of Bzyb of the Gagra region, in Ochamchyr and Sukhum.

However, there are many who even leave Abkhazia after being provided with housing.

Work, language, salary – why immigrants have a hard time in Abkhazia

Immigrants have a rough time in Abkhazia, first of all, to unjustified hopes and excessive idealization of the historical homeland, repatriate Mert Kujba believes.

Mert, 34, moved to Turkey from Abkhazia three years ago. He was not able to find a permanent job during this time, and he is therefore still deciding whether to bring his wife and daughter to Abkhazia.

“My wife works as a teacher in elementary school. Here she will not find work in her specialty, because she does not know either Abkhaz or Russian”, he said.

By profession, he is a plumber, and lives off orders from residents, occasionally moonlighting at construction sites.

This is what happens most often: repatriates in Abkhazia work at construction sites, factories, or in the field of trade.

“Even Koreans are building houses for repatriates in Abkhazia. I don’t understand why – even among the repatriates themselves there are a lot of builders, electricians and plumbers. I and a group of guys who came from Turkey to Abkhazia even thought of leaving to work in Russia. So far this thought has been abandoned. And then I don’t know, I will either change the scope of work, or I will return to Turkey,” he says.

Mert admits that returning to his historical homeland, of which he had practically no idea about before moving, was a pure adventure.

“The first thing you come across is language. In Abkhazia, it is not enough to know Abkhaz. Without the Russian language, you can’t do anything here. I’m still learning, don’t understand everything, and people don’t always understand me,” Mert says.

At the same time, he is sure that for those who want to stay, there will always be a reason and an opportunity.

“I grew up in a Turkic-speaking environment, but I never felt a part of Turkish culture. We studied Abkhaz dances, learned the history of a kind, of our country. We had our Abkhaz community in Turkey, we had a close relationship with each other. I was finally happy to be at home, among my own people. There are difficulties, but a solution can also be found,” Mert is sure.

Mert’s family lives in the Turkish province of Sakarya, where there is a large Abkhaz diaspora. Many Abkhaz families in Turkey managed to preserve the language and traditions, despite the fact that, per Turkish law, they had to change their original Abkhaz surnames to Turkish.

Mert says that in his family they always talked about Abkhazia as the promised land, which they dreamed of seeing again.

“We know that our great-great-grandfather went to Turkey by ship from the port of Sukhumi. About where exactly he lived in the Caucasus, we have no information. There are none of his personal items preserved either. Although my grandfather said that there was a lash in the house for the horse, which the great-grandfather allegedly brought with him. But it was probably lost before I was born,” says Mert.