Hepatitis C in Georgia: Can the “silent killer” be beaten?

Thousands of people have made a complete recovery from hepatitis C. However, whether this unprecedented programme for the eradication of hepatitis C will reach its successful conclusion remains to be seen. Little more than a year remains until its completion, and there is still no answer to the central question: whether Georgia will become the first country to completely defeat the “silent killer”.

Several years ago hepatitis C was considered an incurable disease. The existing drugs didn’t work for everyone, and treating hepatitis C is very costly (as much as 80,000 dollars). People sold their homes and apartments and went to get treatment abroad. Many quit in the middle of treatment because of the awful side effects.

For Georgia, hepatitis C is a serious problem. According to research from 2015, within the country there are as many as 150,000 carriers of the virus, equal to 5.4% of the adult population. In European countries, the number of people suffering from chronic hepatitis C is no more than 0.5-1%, or in the event of widespread transmission, 1.5-2.3%.

• How HIV-positive people live in Georgia

• Marijuana use in Georgia – what does the new law say?

• Measles in Georgia: an outbreak of ignorance?

• Drug policy in Georgia – giving up on reprisals?

It is because of these alarming numbers that this project, the first of its kind in the entire world, began in Georgia of all places. The programme for eliminating hepatitis C began in April 2015. The Georgian government is carrying it out in partnership with the World Health Organization and the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

From the beginning, aid was provided to patients in the most severe condition. They were given medications, the cost of which often exceeded the value of all their belongings.

The ambitious programme’s goal was declared to be the complete eradication of the disease within five years’ time, and the prevention of its further spread.

From April 2015 to April 2020 it was necessary to provide examinations and treatment for 135,000 people (90 per cent of all those afflicted with the disease). Nearly 116 million lari (around 43 million dollars) was allocated for the programme. This does not include the cost of the new Sofosbuvir and Harvoni medications, which exceeds a billion dollars each year. They are provided to Georgia free of charge by the American pharmaceutical company Gilead.

Over the past three and a half years, 51 thousand people have undergone treatment, and 98.2% of them have been fully cured. Another 1.5 years remain until the end of the programme.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=90&v=_jyH5VLXvuA&fbclid=IwAR0g_GRF7GL4AoqoSPWbA0uPcwH1ojbmXY86g3rKXNyRoP1bXa7f471w_s0

“I was pregnant when I learned that I had the virus”

Ia underwent regular examinations ten years ago, when she was expecting a child. The hepatitis C that was discovered in her blood was a shock for her. She couldn’t understand how she had managed to get infected. She took her own appliances with her when she went to the beauty salon, and she hadn’t had any operations or blood transfusions.

After Ia, her husband Dato also got tested. He was also found to have the virus. The examination revealed that his liver was in an even worse condition.

“It was clear that I had infected my wife. How I got infected, I don’t know for sure, but in my youth I took drugs several times, got a tattoo, and went to the dentist,” says Dato.

After the husband and wife learned of the price of treatment, they didn’t dare even dream of being cured. They lived together with two young children in a rented apartment. Where would they get hundreds of thousands of dollars?

Years passed, and Dato’s condition got progressively worse – his liver swelled, the skin on his face began to yellow.

The programme saved them, and essentially gifted the family a second life. After the three-month course of treatment, the virus no longer remains in the blood of 43 year-old Dato and 37 year-old Ia.

“The silent killer”

There are no precise statistics regarding the global incidence of hepatitis C. You can be infected with it at the dentist’s office and at the barber’s shop. The virus can be carried for 20-30 years and go unnoticed. Then one fine day you find out that you have cirrhosis of the liver. Because of this it’s called the “silent killer”.

The World Health Organization estimates the global number of those suffering from hepatitis C at 71 million, though this is the minimum. Each year as many as 400,000 people die from related complications.

This disease is curable in 98% of cases. In contrast to interferon, which was used to treat the disease a few years ago, Harvoni has almost no side effects. But it is expensive: a three-month course costs 80,000 dollars. Due the high cost, treatment is often inaccessible even for denizens of wealthy, developed countries.

Sell the medicine and die

Forty-seven-year-old Tsitsino (name changed) lives together with her paralyzed mother in Zugdidi, in a housing project for refugees. She makes money selling spices in the market. Sometimes she can’t manage to sell anything during the day, and can’t bring food home.

Over the span of three months, she traveled to the city hospital once every two weeks to receive the next dose of the expensive medicine for treating her hepatitis. She found out by accident that she was infected: refugees were provided with free screening as part of the programme.

“I didn’t get a blood transfusion, I don’t go for manicures and I have any money to go to the dentist. I have no idea where I got hepatitis from,” she says. She’s disappointed they don’t just hand over the medicine, since she could sell it instead of taking it.

“They’re being clever. They know that many people are so poor that they would prefer to die and give this money to their children. Many people think the same way as I do. This is why they make us take the medicine in front of a camera,” says Tsitsino.

How the program works

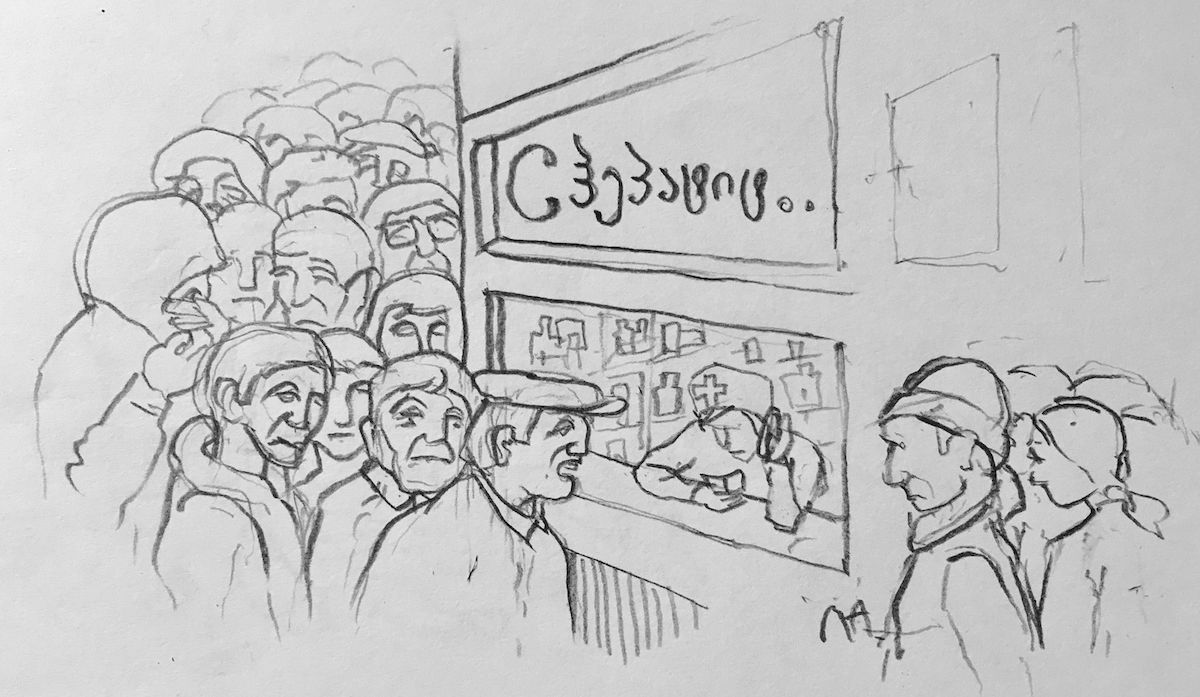

For each patient the programme begins with an analysis. If the screening uncovers hepatitis, the patient is put on a register and waits to be called up. The wait can be up to two months. Then, the patient is assigned to one of the medical centres taking part in the programme.

The medicine is administered every two weeks. Documents must be signed, and the pill must be taken in the clinic, under video surveillance, so that they can document that it is being taken by an actual, specific patient.

Screening centres are operating in twelve cities around Georgia. Special departmens have been opened at public service halls (institutions where citizens submit all sorts of documents) which provide hepatitis C analysis. The screening takes 20 minutes, and the result can be received via telephone. Since 10 October, 6,500 people have undergone screening at the public service halls, and the virus has been discovered in 180 of them.

25,000 people with the virus are refusing treatment. Why?

In order for the programme for the elimination of hepatitis C to reach a successful conclusion, another 84,000 people will have to receive treatment in the remaining time. But as the programme includes ever fewer people, it becomes unclear whether this plan can be successfully carried out. In 2006, 24,000 people received treatment, while in 2017 this number was 17,000. In the past ten months of 2018, only 10,000 have been treated. The strangest thing is that there are 25,000 people who are well aware of their diagnosis, but in no rush to receive treatment.

Experts say there are several reasons for this.

The first is money: to be included in the programme one must first pay to have several analyses performed. At first the cost ranged from 400 to 700 lari (150-260 dollars), but now the cost has been reduced to 110 lari, but for many this is still an obstacle.

Secondly there is geography: the clinics are located in cities, and one must travel there once every two weeks. For example, residents of Samtskhe-Javakheti must travel 200 kilometres to Tbilisi. The government is currently considering how to decentralize the programme.

Another reason is the country’s drug policy. According to recent data, there are 55,000 users of intravenous narcotics in Georgia, and seventy per cent of them, as a rule, are infected with hepatitis C.

“When a person is imprisoned for using a needle, or taken to get tested by force, it’s impossible to bring that individual out of the shadows and draw them to the programme. So long as the country’s drug policy is not liberalized, we shouldn’t hope that hepatitis C will be defeated,” says Koka Labartkava, a representative for the Georgian Drug-Users’ Network.

Russian propaganda and love of wine

There’s one more important reason why people don’t go for treatment, which is disinformation: Russian propaganda has gone after Georgia’s hepatitis C elimination programme.

Representatives from the ministry of defence and foreign affairs of Russia, and media organizations controlled by the government, recently unanimously asserted that in Georgia, under the guise of treating hepatitis C, experiments are being performed on people, as a result of which there have supposedly been “dozens of fatalities”. And this cruel experiment is supposedly being carried out by the Lugara American biological laboratory in Tbilisi. Despite the obvious absurdity of this story, the campaign was taken up by anti-Western websites in Georgia.

“After each wave of disinformation, the number of those wanting to be included in the programme falls catastrophically,” says physician for infectious diseases Maia Butsashvili.

She mentions one more, astonishing reason why people refuse treatment.

“A person might say, for example, that they have three tons of homemade wine at home, and can’t start treatment until they’ve drunk it all.”

Who can be infected?

In short – anybody. Hepatitis C, for which there is, as yet, not vaccination, is a blood-borne illness. The virus must enter the bloodstream of a healthy individual. It enters hepatocytes – cells in the liver – multiplies, and damages the lining of the liver. The illness often goes without any symptoms whatsoever, until it is too late.

How can one be infected? By:

— coming into contact with unsterilized medical instruments;

— using intravenous drugs;

— coming into contact with things like a toothbrush, scissors, or razor of an infected individual;

— having unprotected sex with an infected individual. However, such cases are so rare that the World Health Organization doesn’t include hepatitis C among sexually transmitted infections.

With access to medication and treatment it’s not difficult to be cured. However, a person who’s been cured will nevertheless have to change their lifestyle, refraining from alcohol and heavy, greasy foods.

Why Georgia?

Specialists speak of two, primary reasons for the spread of hepatitis C in Georgia: non-sterile instruments, and intravenous drug use.

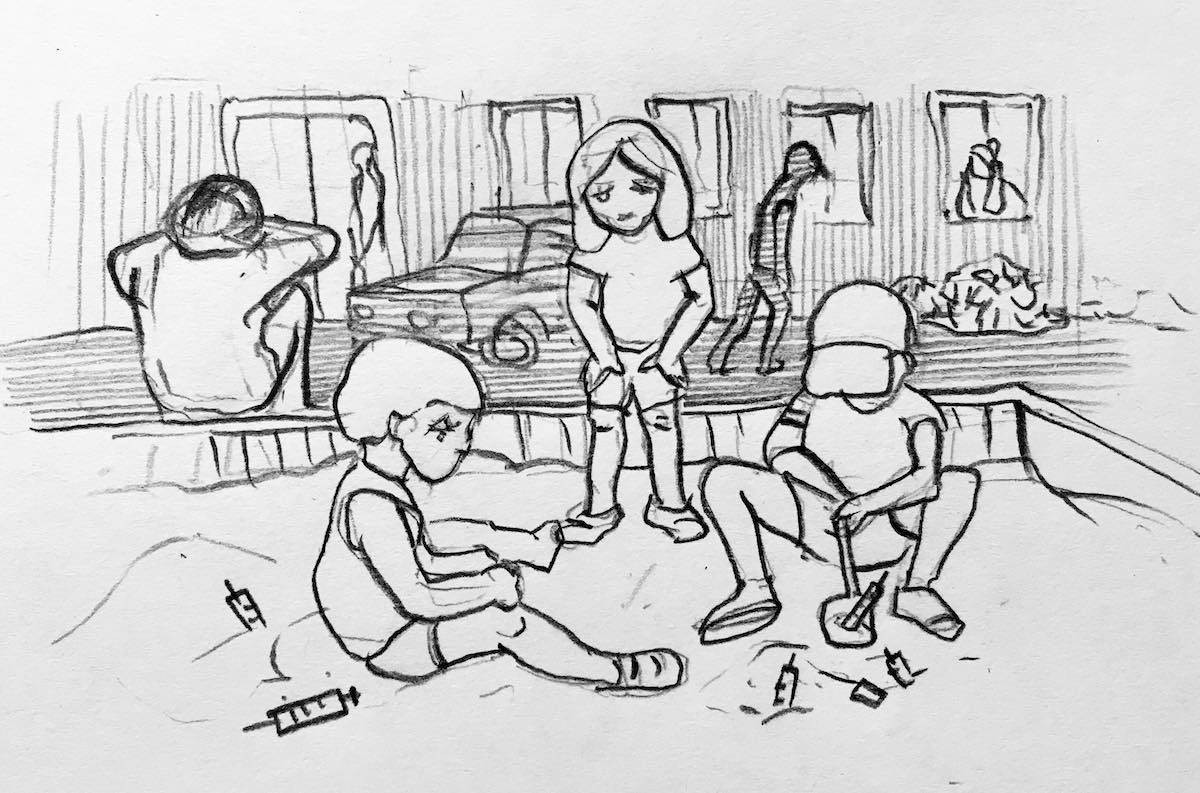

The 1990s was a time of chaos and destruction, and precise statistical records of drug addiction were not kept in Georgia, though its epidemic levels were noted. Squares and courtyards were littered with used needles which children played with.

There was also no monitoring system for medical institutions. And medical instruments were sterilized using primitive methods. When there was no electricity, they were “boiled” on wood-fire stoves. Nobody trusted donor blood.

Georgia was chosen for this experiment because in this small country where hepatitis is so widespread, it’s easier to administer such a programme, and there is a developed medical infrastructure in the country. “High-level lobbying” abroad also played a role.

What’s next?

Egypt is one of the leaders in the fight against hepatitis. From 2008 to 2011 a special programme was carried out there in which 90% of 190,000 patients were cured. But hepatitis C spread once more afterwards. Within a year after the programme’s completion, 100,000 new cases of the infection were discovered.

The primary reason is that nothing was done to prevent the spread of the illness: intravenous drug use, medical institutions, and barber shops remained the primary vectors for the virus, as before.

In 2015, more than 2,000 barber shops and beauty salons in Georgia were inspected. It was discovered that the majority of them were violating norms for sterilizing instruments.

According to the manager of a prestigious dental clinic, Nana Murusidze, until 2015, the Ministry of Health didn’t even keep a register of dental clinics.

“They didn’t even know how many clinics there were. One time I even saw a dentist’s office in a market in Batumi.”

Then the regulations were tightened, but there is still no mechanism for monitoring whether or not they are being observed.

Irina Onashvili, owner of a beauty salon, says that the salon has been operating since 2012, and that in this time nobody has inspected the sanitary conditions in the salon.

“We recently purchased a new, sterilizing appliance for 1,200 dollars. We are constantly renewing our equipment and instruments. But this is our choice. We are under no obligation to do so. Our clients trust us, and nobody has been infected with anything for all this time.”