My Karabakh - Part V: War

This is the fifth installment in a series of essays written exclusively for JAMnews by Armenian journalist and writer Mark Grigoryan.

The first four installments can be found below.

My Karabakh – Part I: Hadrut, a donkey, water and a brawl

My Karabakh – Part II: 1988 – The Karabakh protests begin

My Karabakh – Part III: Summer of 1988 – Yerevan demands that Karabakh be returned

My Karabakh – Part IV: The Sumgait Chronicles

My Karabakh – Part VI: Baku and the hands of Heydar Aliyev

My Karabakh – Part VII: conclusion – Baku vs. the BBC, epilogue

year 1988 was crashing to an end.

In November, a Moscow court had begun a pitiful excuse for a trial for the Sumgait pogroms. It was just one of many trials. They distilled a criminal case down to a number of less severe offenses in an attempt to avoid having to call it for what it was – violence on ethnic grounds. The offenders were tried in Volgograd, Voronezh and other places as well.

A number of cases were sent to Baku and Sumgait. As a result, the feeling that the thugs responsible for the massacre had remained unpunished only grew.

This only worsened the situation and pushed the conflict further.

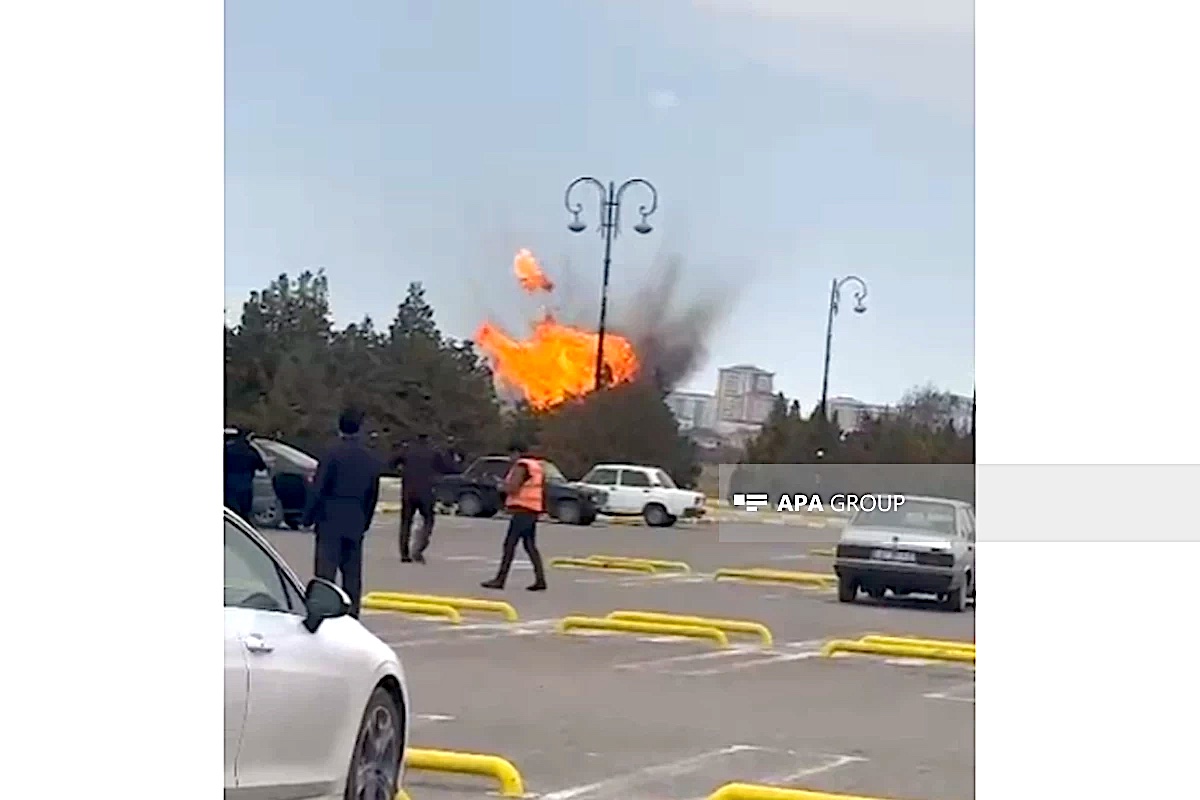

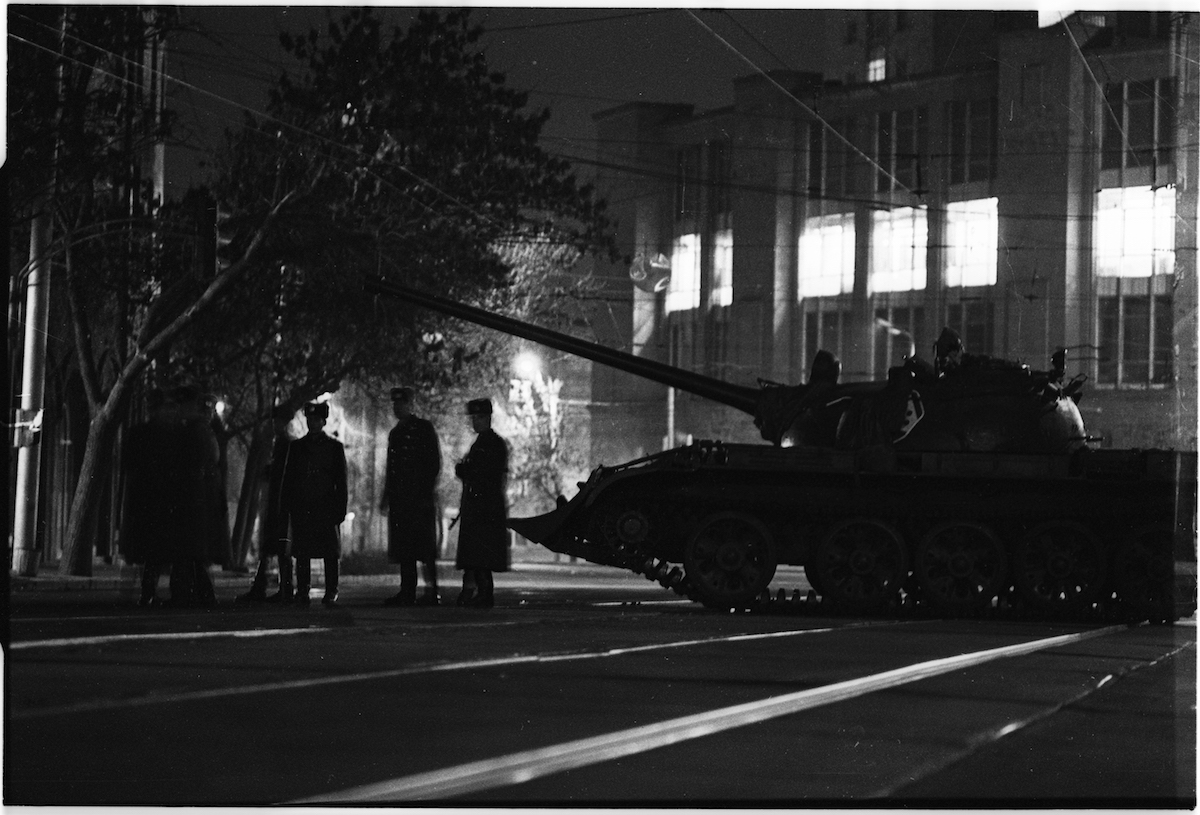

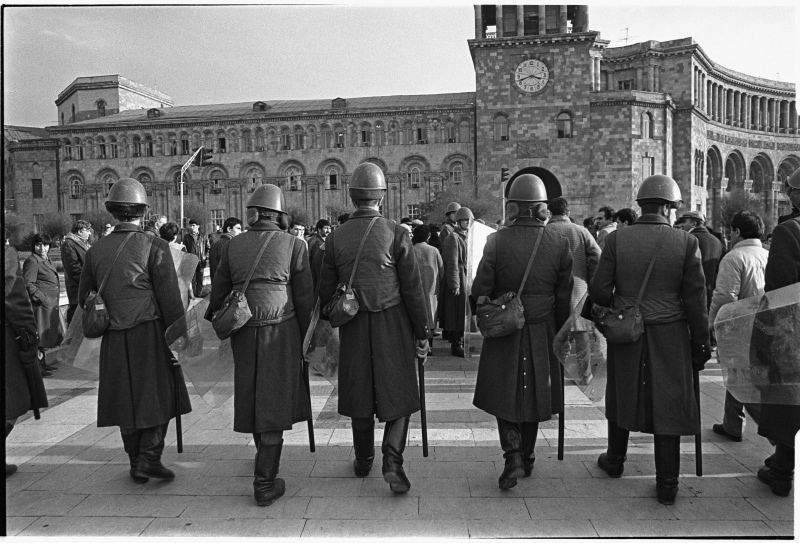

On 23 November, when a huge crowd had gathered by the opera where an emergency session of the Supreme Council was taking place, the authorities imposed a curfew. Tanks and armored vehicles moved laboriously through the streets that night.

We couldn’t leave the house after 10 o’clock. They’d snatch up anyone who did – even those who had gone out in their slippers just to throw out the trash. The standard punishment was 30 days imprisonment, and people were taken away without discussion.

Things ‘normalised’ a few days later. Soldiers who had earlier menacingly sat on their tanks began walking into apartments and begging. The people of Yerevan fed them, and gave them cigarettes and vodka.

At 11:41 in the morning on 7 December, I was holding a class for eighth-graders when a sudden rumble shook the ground. The girls screamed. I looked out the window and saw how two ten-story buildings across the street leaned towards one another, and then sharply swung the other way. The school building itself was shaking.

It was the Spitak earthquake.

Thenext few days disappeared into an unending nightmare. Time lost its fluidity, and broke apart into individual, unconnected images.

That’s how I remember them – as images, the unidentified bodies of the deceased, laid aside in several rows near the foundation of the monument to Lenin in Leninakan (now Gyumri).

Dozens of coffins – stacks of them – dumped into the stadium in Spitak.

People reading lists of the wounded posted at the doors of the Yerevan hospital.

A moaning woman, crawling on the outside of a tilted building towards where the rest of her family was trapped under the debris.

For many, the earthquake and the Karabakh movement became inseparable. It’s exactly for this reason that there are a number of people in Armenia who swear by the conspiracy theory that the earthquake was brought about artificially.

Now, thirty years later, I look back and think that 1988 began for me on 21 February and ended on 7 December. During these months there were so many experiences, so many events, emotional peaks and plunges, that the year felt as heavy as several years.

War

“M

ark Vladimirovich,” said a boy approaching me. “Don’t tell our parents, but we’ve decided to run off to the war.”

There were three boys. They were 14 years old, and I was the teacher of their class. The conversation took place in class. By that time, the war still hadn’t started, but things were clear enough: it was unavoidable.

It was fall of 1991. The August Coup in Moscow had failed, and all the Soviet republics and autonomous regions who was able to declared their independence. Azerbaijan had exited the Soviet Union, Armenia held a referendum and became an independent state, and Karabakh announced its separation from Azerbaijan.

But things were not calm in Karabakh. One of the three teenagers standing in front of me was from Getashen, a village in the north of Karabakh, which in the spring of 1991 became the epicentre of the Koltso [Rus. ring] operation, conducted by Soviet forces and Azerbaijani special purpose units.

They entered the village having suppressed the resistance of its residents who were supported by volunteers from Armenia.

The special purpose units robbed homes, beat local residents and killed several people. The rest of the population was deported. Azerbaijanis were brought into Getashen and Martunashen to settle the emptied Armenian homes.

My student Avetik* was getting ready with his two best friends to make his way to the village where his family had lived in order to take revenge.

The boys said they were telling me this because they felt an adult should still know about their plans.

And that created a difficult situation for me: as their teacher, I had to tell their parents. But if I did so, I’d lose their trust forever. I should have taken the responsibility on myself and dissuade them from this crazy and perhaps suicidal trip.

But how?

I couldn’t forbid them – it would only further embolden them to run off to war. I told them that they could do so, but that they had to prepare themselves and pay particular attention to physical fitness, because there’s no place for weaklings at war.

The three friends began exercising every morning, running, stretching. They learnt to orient themselves directionally and use a compass. They started saving money.

A few months went by in this fashion. Winter started, and the escape had to be put off until spring. And when spring came, they were distracted by something else, and they placed their plans on the back-burner.

here was no use for me at the front – people like me were not supposed to be put forward to face cannon fire, the government felt, and no attempt was made to enlist me into the army.

But many did fight. Including my friends, acquaintances, neighbours and colleagues from the Yerevan city council, of which I was a member in the beginning of the 1990s.

People served in the war in different ways. Some went to Karabakh for a few weeks and then came home and proudly strut about in their freshly-pressed camouflage uniforms. They wouldn’t part ways with their automatic weapons. They stepped in a particular way, and with their glances demonstrated to all around them their seriousness and significance.

But there weren’t many of them. My friends who had left for Karabakh, most of them didn’t return home for months. And once back, they immediately began preparations for returning to Karabakh.

War is tragic. My friend and university classmate, journalist, publicist and political figure Samvel Shakhmuradyan was killed. Simon Achikgezyan, a colleague at the city council was also killed. We had been close, despite the fact that Simon, who for his grey hair and beard had been called ‘Ded’ – Grandpa’ – was an entire generation older than me.

And there were many funerals. Young boys, killed on the fronts of Karabakh.

War is a series of retreats and offensives. Taken and surrendered hills and villages: mud, sweat, blood, rot and nightmarish, inhuman fatigue which invades not only the body but, it would seem, the soul as well. And the stench of excretion, rotting flesh…

In this way, the Karabakh war wasn’t different from the dozens of other wars of the 20th century. It was just as wicked, irreconcilable, aggressive and inevitable.

People fought desperately. In Armenia, everyone understood: the surrender of Karabakh would mean the surrender of Armenia. For that reason, every populated area, every hill and mountain, every woodland was fought for.

Azerbaijan, at different periods, was aided by Ukrainian pilots, Chechen detachments, mercenaries from Afghanistan… however, the Armenian side was able to organise itself quicker, to create something like an army out of separate guerilla units and eventually, to turn them into real soldiers.

The situation was complicated by the fact that when the USSR fell apart, there were many more weapons on the territory of Azerbaijan than in Armenia, which gave the Azerbaijani soldiers a significant advantage in equipment and weapons.

People said that Monte Melkonyan, who was one of the organisers of the Armenian army and the commander of the Martuni district, did not praise his soldiers for retrieving damaged tanks. He punished them:

“You have to shoot at tanks in such a way as to overtake and then use them,” he’d say.

Over time, the Armenian Karabakh army was able to withstand serious offensive attacks, and soon was able to begin enacting their own, as a result of which a number of regions were conquered which were already outside the boundaries of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast [region] of Soviet times.

And that’s when the cease-fire agreement was signed. It would seem that this is the only agreement in Europe of its kind, the implementation of which is not provided for by peace-keepers, but by the conflicting sides themselves.

They’ve been at it for twenty years, and what’s more there’s no ‘green’ or demilitarised zone.

But the war was still on when I understood that it contradicted my attitudes towards life: we were organically incompatible – the war and I. It wasn’t easy to understand this, but it was even more difficult to understand how to live when the Karabakh war was taking place not so far from where I was, and where my friends were dying.

My father and I published an open letter to the intelligentsia of Armenia and Azerbaijan in the Voice of Armenia newspaper. The intention behind the letter was to encourage the two sides to influence their states in order to finally put an end to this war and to begin peace negotiations.

This, of course, was rather naive. Our faith in the intelligentsia was childishly naive: in Soviet times, it had become used to obeying the authorities and was incapable of independent action. However, what was the Soviet intelligentsia? And what is the intelligentsia anyway?

I no longer have answers to these questions.

Despite our naivité, the letter was heard by both Armenians and Azerbaijanis. We received the most positive of responses, but that was about as far as it got.

“War’s never a winning thing, Charlie. You just lose all the time, and the one who loses last asks for terms. All I remember is a lot of losing and sadness and nothing good but the end of it. The end of it, Charles, that was a winning all to itself, having nothing to do with guns.”

Sometimes I argue with Bradbury, but more often I agree. Guns have nothing to do with winning a war.