How HIV-positive people live in Georgia

The first case of HIV/AIDS contracted in Georgia was recorded in 1989. Since then much has changed. New methods of treatment and medications have emerged through which HIV has become a chronic, manageable disease instead of a death sentence. In regard to Georgian society, however, little has changed for HIV-positive people. Stigma and discrimination are still an insurmountable problem today.

HIV is still associated with death. Many people still don’t know how the infection is transmitted, and avoid contact with infected people.

JAMnews spoke with a few people who have been living with HIV for years, as well as those who communicate directly with infected people.

Tamuna, 34:

Tamuna, who now helps other infected people, contracted HIV nine years ago in prison. To this day, she doesn’t know how she was infected. She thinks it happened either during an operation she had to remove her cecum, or from a dentist. Since then, her life has changed.

“After that, when I openly said that I was HIV-positive, only a few prisoners out of 1,800 in the female colony would communicate with me. I saw how close friends distanced themselves from me, how I became a stranger to them. I felt unwanted because I saw that people avoided relationships with me,” Tamuna said.

She said that even her relatives barely accepted her diagnosis: “You know, in Georgia there’s a stereotype that a person with AIDS is a drug addict or sex worker.”

• New drug policies: what can we learn from Portugal’s example?

• Measles in Georgia: an outbreak of ignorance?

• “I am so angry I can’t breathe” – Georgia: stories of people injured at work

She said she not only faced discrimination from prisoners but also from doctors. After her release she wasn’t able to find a job. She said that, because she didn’t hide anything about her health, doctors refused to see her.

An art therapy course has been helping Tamuna in overcoming her challenges. “I embroider, draw, and make decorative pillows, and it helps me a lot. I’m being treated, I take medicine, and I know that I must take it for the rest of my life. If the virus isn’t active in my blood, I live just like everyone else. I’m just constantly monitoring my health and frequently doing tests.

“I don’t hide my status. I want to be an example to all, and tell women who are HIV-positive that they can give birth to healthy children and shouldn’t give up that joy. I have three children, two of them who I birthed after I contracted HIV, and both of those children are healthy. I am HIV-positive, but I’m not a danger to society,” says Tamuna.

Art therapy helps Tamuna and other infected people cope. Photo: Nino Memanishvili, JAMnews

Tariel, 39:

“I learned that I’m infected at the end of 2015. Before that I had been sick for several months, and the day before the new year I learned the results of my HIV test. It’s hard to describe what happened to me. I was really frightened, even cried. I went through hell. It took me two months to come to terms with the diagnosis.

There was no one nearby that could give me advice or share information. In the end, I found a Russian-speaking group of HIV-positive people on the internet. They shared their experiences, gave advice, and calmed me down. I’m being treated now and have to take medicine for the rest of my life. I’ve had to change my way of life of course.

I was a good toastmaster and loved to drink. Now I don’t drink. As far as the rest goes, I live like normal and don’t limit myself in anything. I don’t hide that I’m HIV-positive. The only person who doesn’t know is my mom. She is so sick, I don’t want her to worry. Now I warn everyone to take care of their health. I contracted HIV as a result of unsafe sex, and I want others to take this mistake into account.

To anyone who has just learned that they are HIV-positive and cannot get out of shock, I want to tell them to not be afraid, HIV is not a death sentence!”

Zaza, 32:

“I discovered I had HIV 7 years ago. I don’t know how I got infected; apart from having unsafe sex I also went to the dentist. I was discriminated against even by family members: They began to avoid physical contact with me, and gave me a separate cup and plate. For a long time I couldn’t convince them that HIV isn’t transmitted through hugs and kisses.

I had a girlfriend and I felt it was necessary to tell her about my diagnosis. After that she broke up with me.

I’m being treated and feel well, but I don’t talk openly about my diagnosis. I probably won’t talk about it while the level of social consciousness is so low.”

Infectious Disease Specialist Maya Butzashvili

Maya is one of the first doctors to treat HIV-positive people in Georgia. She says that infected people still suffer discrimination.

“I remember that in 1996, an HIV-positive person died and no one came to his funeral service. There was a case of one patients’ home being burnt down. Doctors refuse to treat them. In Tbilisi, there was only one gynecologist who accepted HIV-positive women 15 years ago. I can’t say that the stigma towards HIV-positive people has lessened much.

Despite the fact that they are not particularly persecuted or oppressed, society nevertheless is intolerant towards HIV-positive people.”

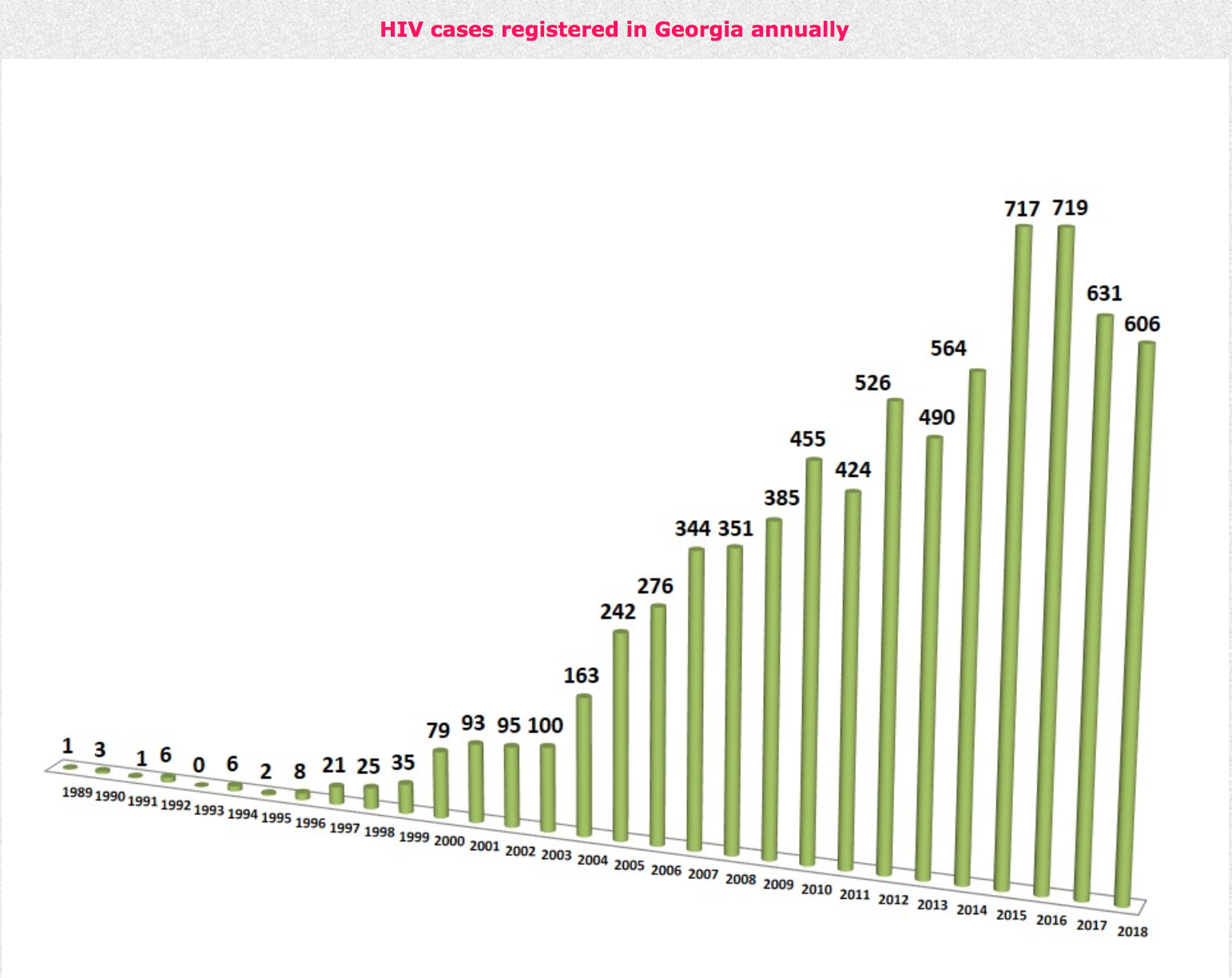

Statistics: 606 new cases in 2018

The estimated number of HIV-positive people in Georgia is about 7,000. According to worldwide statistics, Georgia belongs to the group of countries with low HIV/AIDS prevalence, taking the last place among them. However, 7,000 cases is still a solid figure for such a small country.

The latest statistics are as follows:

As of 27 November 2018, 7,368 HIV infections were registered with the Centre of Infectious Diseases, AIDS and Clinical Immunology in Georgia – 5,517 infected men and 1,851 women. Most patients are between 29 and 40 years of age.

Since 1989, 3,816 were diagnosed with AIDS in Georgia, of which 1,500 have died. In 2018, 606 new cases were registered. In total 4,524 people are undergoing anti-retroviral treatment (526 of them are from Abkhazia).

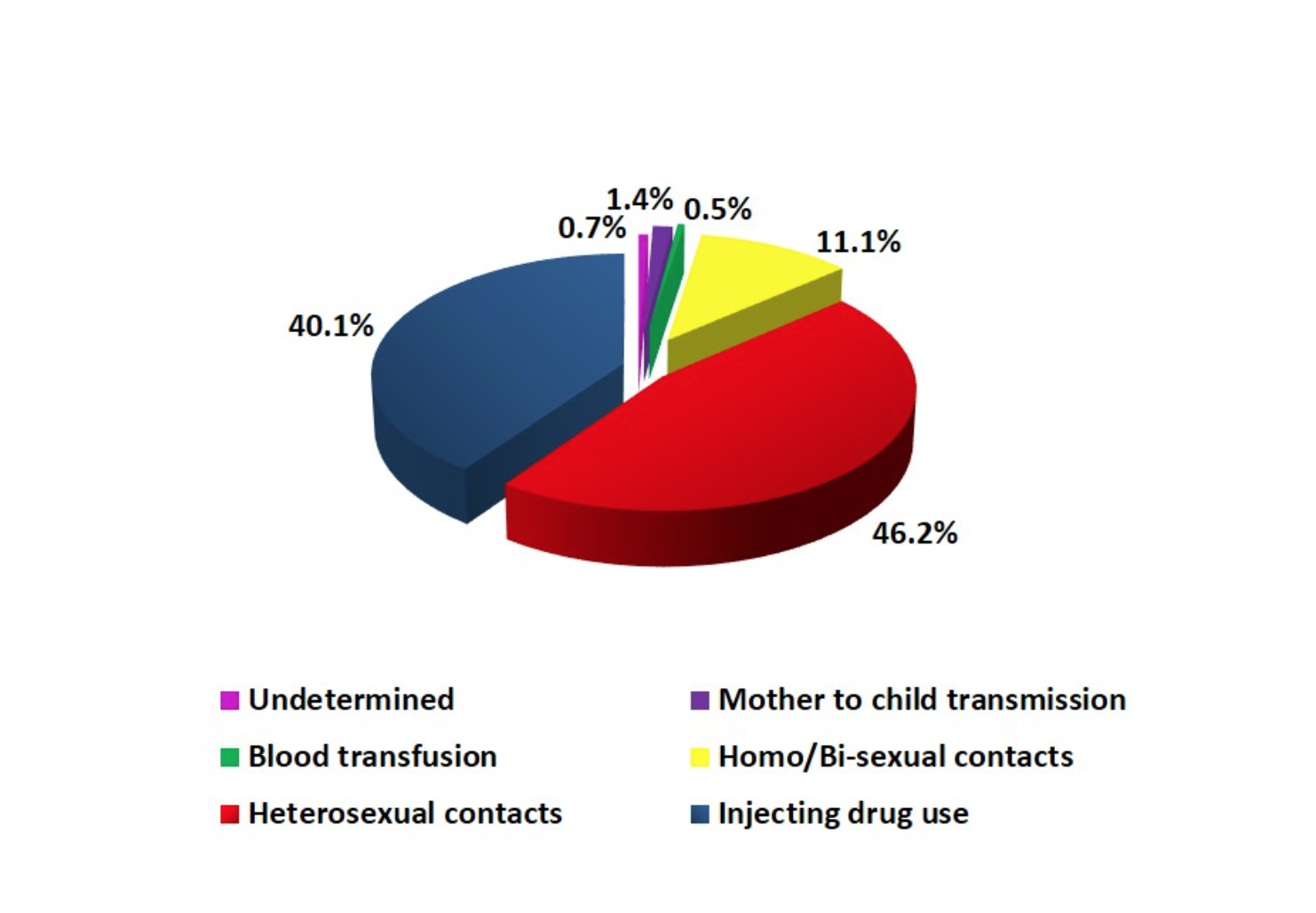

According to the AIDS Centre, 40.1% of those infected were drug users, 46.2% were infected through unsafe heterosexual activities, 11% through unsafe homosexual and bi-sexual activities, about 1.5% contracted it ‘vertically’ from their mothers during pregnancy (there are 103 HIV-positive children in Georgia), and about 0.5% contracted HIV from blood transfusions.

What is HIV?

Even now, many people associate Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) with death, and people infected with it to being drug users, homosexuals and prostitutes. It is still difficult for people to believe that other categories of people can contract HIV. Many still don’t know how HIV is transmitted and avoid basic contact with carriers of the virus.

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) was discovered at the end of the last century. An epidemic began in 1981 in the United States which later spread worldwide. The virus is presumed to have entered the US from Africa.

The body’s immune system is weakened by the infection. The virus can go unnoticed for several years before it develops into AIDS – Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. Having HIV does not mean that a person has AIDS. An infected person will develop AIDS only if they are not treated. Their immune system weakens to the point that it cannot handle any illness.

Today, HIV is no longer a death sentence. While there is no way to get rid of the virus completely, it is possible to stop it from reproducing and weakening the immune system.

Thanks to modern methods of treatment, HIV has become more of a chronic disease. The virus remains in the body but doesn’t harm it. With the help of treatments, patients can live a full life.

Treatment is more effective if the virus is detected early on. People who are infected take one or two pills a day, and the drugs have almost no side effects. The most important thing is that a person following the course of treatment no longer distributes the virus.

Early detection is incredibly important for pregnant women: if an infected mother takes the right drugs during the first trimester, the child will not become infected.

Modern treatment is also important because it helps to prevent the spread of HIV. As a result of treatment, the virus’ presence in the body is reduced, minimizing the patient’s ability to spread the infection.

The diagnosis and treatment of HIV/AIDS is free of charge in Georgia. The programme is co-financed by the Georgian government and the Global Fund.

The Global Fund also finances harm reduction programmes. As part of the Harm Reduction Network which operate in 11 Georgian cities, there are 14 centres that offer various services to injecting drug users. They are provided with single use syringes and offered various kinds of medical assistance. One of these centres is called NERA+. The centre’s director, Professor Manana Sologashvili, told us about some of the problems that HIV-positive visitors to the centre face because of their diagnosis.

Three methods of HIV/AIDS transmission:

- Unprotected sex.

- Through blood (unsterile medical instruments, syringes, transfusions of infected blood).

- Vertically, from mother to child.

HIV/AIDS is not transmitted by airborne droplets, through handshakes, kissing, hugging, using a shared bathroom/toilet or through safe sex.

Recent trends identified in Georgia

- Recent research indicates that the spread of HIV through the use of drug injection is not increasing. According to Mac Gogia, manager of the Harm Reduction Network programme, this is due to the free distribution of single-use syringes.

- The number of cases of HIV transmission from a man to a woman through heterosexual intercourse has grown.

- The number of people infected in hard-to-reach groups such as men who have sexual contact with other men has increased.

Main challenges

- Late diagnoses. Marie Chokheli, coordinator of the Open Society – Georgia public health programme fund, said that some 103 children would not have been born with HIV if their mothers had been screened.

- An uninformed population which causes continued spread of the virus on one hand, and stigma and discrimination of those infected on the other.

- The Global Fund, which finances treatment programs for AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, will phase out its activities in Georgia by 2020. Financing for these programmes will need to be provided entirely by the government. Currently, the state partially funds the purchase of medicine, but it is not yet clear whether it will finance harm reduction programmes.

- Georgia’s drug policy, which calls for criminal prosecution of drug users. Experts say that it will be difficult for the state to finance a harm reduction programme since recipients don’t trust the government. “The Global Fund currently distributes syringes anonymously, but how can the state spend money on anonymous users? Drug addicts won’t come for syringes if the program isn’t anonymous,” says Maka Gogia.