Who do Baku's lions safeguard?

An old bath-house in Baku

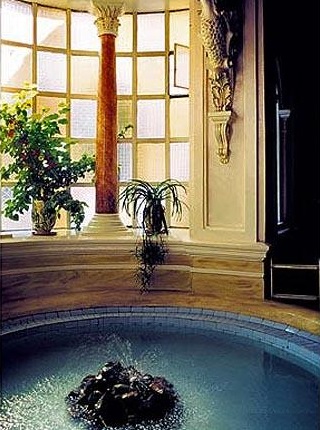

The famous Baku-based “Fantasy” bath-house, which is located at the intersection of Vidadi and Safarli streets, slightly above Fountains Square, was opened on 13 January 1897. The ‘Caspian’ newspaper issued a rather pompous article regarding this. The author questioned the investors’ chances to see returns on the invested funds, as “Fantasy” was too well-wrought and luxurious.

Nowadays, a man would get up in the morning, take a shower, have a cup of coffee and rush to work, whereas in the bad old times, when there was no running water or sanitation, the washing process was ‘no bed of roses’. Once you had lived up to 40 and didn’t have too bad an odor, you could consider your life as successful.

The stone head of a time-blackened lion is hovering above a stone washstand, which isn’t filled with water, but rather with plastic bottles, napkins and rotten leaves that have remained there since autumn. Earlier, an elderly woman with a small broomstick would come here and clean it. She hasn’t showed up here for quite long.

How it all began

The bath-house owner isn’t known. The bath-house was designed by Nikolaus August von der Nonne, a member of the municipal administration and later the head of City Administration, a compiler of the city’s master plan. If that’s true, then the building could possibly be on the city balance and the absence of a private customer could be attributed to it. Indeed, why would the city head, who was all wrapped up in work, construct a privately ordered building?

‘Fantasy’ was the first commercial facility with a power supply (and a phone number). Spiral electric light bulbs were a marvel of the modern engineering thought. Before that, only public institutions (including the railway station) and the houses of well-off people were supplied with electric power. Multi-color lamps illuminated the hall fountain,” the Caspian’ newspaper explained.

The entire lighting system, both indoors and outdoors, was electrified. There were lanterns hanging in the corners, illuminating the above-mentioned lions, and an electric headlight was sticking out of the roof like an ostentatious extravagance.

There was a special hall for a tea party after the procedure, and there were tea tables in the ‘Fantasy’ courtyard.

The bath-house had a marble-faced interior and the floor was also made of marble, but it was different from the one on which our contemporaries slide in slushy weather in the rapidly developing, modern Baku. It was made from specially processed one.

The bath-house featured ‘suites’, that is, 20 solitary bathing-places were arranged there. But it was not for the purpose you’ve just thought about. One would come here, take a bath, discussed a deal with a colleague, talk about life, and there was no fornication.

Each ‘suite’ had a dressing-room, where one could get undressed and leave his belongings, and certainly, there was a bathing-place with luxury single-piece bath-tubs.

There were also stucco moldings, plenty of exquisite stucco – angels, Greek gods, as well as Oriental and Roman-styles ceiling frescos, and there were always fresh flowers in the expensive vases.

20 Servants and waiters, and the same number of maids, were employed at the bath. The service offered newspapers – Russian, French, Persian, as well as magazines. Also, live music was played there, which was replaced in 1900 with a new-fangled phonograph.

There was no water pipeline in Baku up until 1914. The bath-house consumed an unthinkable amount of specially brought fresh water. So, ‘Fantasy’ was sometimes closed for a couple of days, until the stocks were replenished.

Interestingly, the prices in ‘Fantasy’ were low – a minimal service cost just 50 kopecks. That is, even an ordinary worker with an average salary of 20 rubles could come here at least once a month.

Soviet times

In 1920, the bath-house was closed and whatever could be taken away and sold – was taken out and sold. Part of the bath-house was pulled to pieces. The marble was removed and handed over first to the military hospital, and later to school.

However, “Fantasy” was restored in the late 1920s. The carpets were laid and everything was restored and renovated there. But the luxurious restaurant was removed as it was excessive. Now it was just an ordinary bath-house, though still the best one in the city.

“Personally for me, ‘Fantasy’ is associated primarily with my grandmother, who used to sell soda outside the ‘Fantasy’ bath-house. And we lived in the vicinity, in Vidadi street,” says Lyafita, an old-timer Bakuvian. “In fact, there were several bath-houses in this area, among them Bath-house #1 and the Soldiers’ bath-house, where military servicemen used to have a bath. But ‘Fantasy’ was regarded as the best one. I was a child, but I still remember how beautiful it was then. It was in the 50s. We went there quite often, because we usually had water supply problems at home.”

There was a tram that ran from Shemakhinka, passing by the ‘Fantasy’ bath-house in the section facing Gorkov Street. There was a tram stop right in front of the bath-house, which was an advantageous commercial spot in times of famine: there were passengers getting off the tram on one side, and, there were people coming from the ‘Fantasy’ bath-house on the other side.

Soda machines and a confectionary canteen appeared there in the late Soviet period. Having bought a subscription in advance (an hour cost 1 ruble per person), people would go there with children and line up in a long, traditional Soviet queue. The fountain in the courtyard oftentimes didn’t function and natural flowers were replaced with artificial ones.

“We lived in the vicinity, in Vidadi street. My mother would take me and my brother there. I was 6 and my brother was 10. He would lift me up and I would put a coin into the soda machine. Ordinary lemonade, soda and cream soda were available there,” recalls Ismail.

Throughout that period the bath-house remained ‘a hangout’ place, where people would come with big families or companies not only to take a bath, but rather to relax and communicate with others.

There were women and men’s days, but that applied only to the common hall. As for the ‘suites’, married couples were let in after a passport check. The adulterers, however, managed to bypass that system: one could bring in a lover using the wife’s passport. Passports did not have photographs at that time.

Present day

‘Fantasy’ was still operating in 2000 to early 2010, but its luxury had slightly frayed. People mostly went there just to have a bath if the shower at home was broken.

“It had an old repair style. There were stained-glass windows and decadent furnishings in the central hall. One could ask for a cup of tea with jam to be served in the room and it was brought on some cool trolley trays. One could just come and sit in the central hall. There was also a small orangerie and a fountain.”

There were only old, Soviet-time, trolley tables there. On a side note, one could be refused to be served meals allegedly because there were no free tables available and the meals couldn’t be served,” said Farid. “I’ve always liked this bath-house more than others. This building preserves some secrets and you can tell it just by looking at its walls.

A sequel to the renowned Soviet film ‘Don’t be afraid, for I’m with you!’, entitled ‘Don’t be afraid, for I’m with you! 1919’, was filmed in the ‘Fantasy’ bath-house in 2012. This video features the ‘suites’ with crumbling tiles and the central hall of the bath-house, with stucco mouldings and a fountain.

“I think it was in 2010 or 2011, that I went there to find out about the bath-house prices and condition for my foreign friends,” said Nailya. “There were shabby Soviet-time tiles around and battered tile flooring. Stucco remains on the walls were covered with a thick layer of emulsion. As far as I remember from my childhood, the bath-house was closed for repairs in the 1980s and it was then that all frescos and stuccos there were tiled.”

Having recently confused ‘Fantasy’ bath-house with another bath in the same area, Baku social media users started loudly mourning it. Even after it became clear that ‘Fantasy’ was in its place, people kept worrying over its possible demolition, especially as it was closed at the end of 2016. Now, there is an ‘eloquent’ lock and a plaque that reads as follows: the bath-house is an architectural monument and it is protected by state.

Elbar Kasimzade, the Azerbaijani Architects’ Union Board Chairman, commented to the 1News media outlet in almost the same spirit, alleging that it was ‘protected by state’: “An appeal, signed by the chairmen of the artists, architects, composers and writers’ unions, was sent to the President in connection with destruction of architectural monuments in Baku a year ago. Since that time, the demolition of such buildings has stopped and I think no one is going to touch ‘Fantasy’ building.”

Neither the Executive Government, nor the Culture Ministry officials could respond to our inquiry concerning the future fate of ‘Fantasy’ bath-house.

However, an anonymous source in the state agency dealing with urban planning confirmed that a private developer, who had bought this area, was going to demolish the building.

Today, ‘Fantasy’ is a tightly boarded-up, blackened building with smashed windows, which looks as mangy as an old cat. And only 3 gloomy lions, set in the corners, are safeguarding it, collecting plastic bottles and shwarma napkins in their stone trays.