‘Hostages’ - when the end is already known

The world premiere of ‘Hostages’ was held as part of the 67th Berlin International Film Festival. On 20 April, the film, which was directed by Rezo Gigineishvili, will be screened in Georgian movie theaters. The film is based on a tragic story about a plane hijacking attempt that took place in soviet Georgia in the 1980s.

‘Hostages’ is based on a real-life even that happened on 18 November 1983. 7 Georgian youngsters hijacked a TU-134 passenger plane heading to Batumi from Tbilisi Airport.

The plan was as follows: the hijackers were going to land in Turkey and afterward flee to the west, where they thought a good life would await them – in the land of freedom, America.

However, everything turned out differently. The hijackers’ plans where foiled after they discovered that, instead of heading to Turkey, the plane had flown for a couple of hours and landed at Tbilisi airport again.

The plane was stormed by a special squad. There were 57 passengers and 7 crew members on board. 7 people, including 2 hijackers, were killed in a shootout. As is indicated in the case materials, 108 bullets were fired at the plane from the outside.

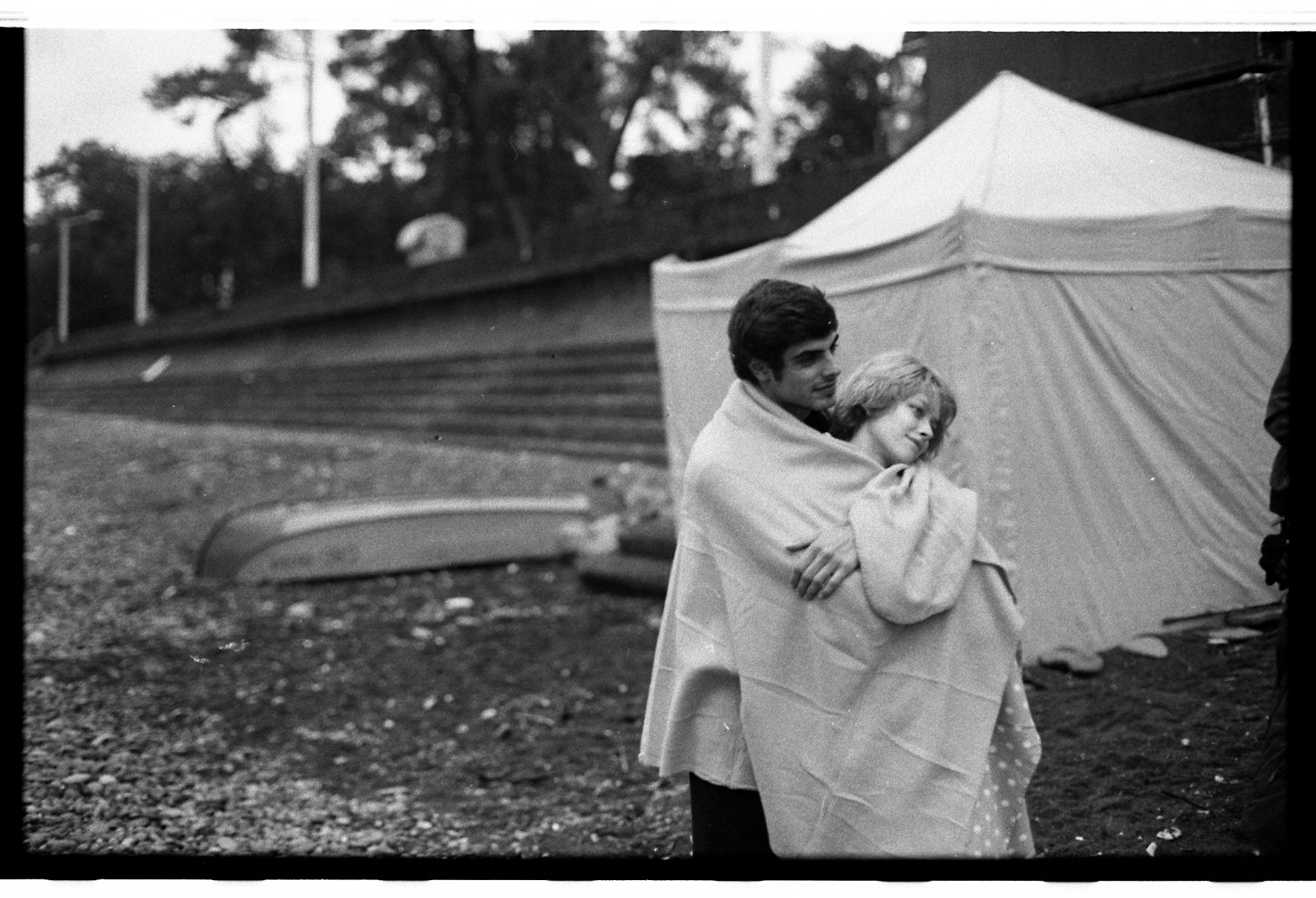

Among the hijackers were Gega Kobakhidze, 22, an actor, and his wife, Tina Petviashvili, a student. The couple got married the day before the incident.

Two hijackers were killed in the plane shooting, whereas the rest were put on trial and sentenced to death. Tina Petviashvili, the only female hijacker, was the only one who had escaped capital punishment. She was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

Rezo Gigineishvili, the film director, was researching the theme for 8 years, collecting materials, getting familiar with the archives preserved at the MI (Ministry of Information) and the victims’ families, studying old interviews and interrogation records jointly with Lasha Bughadze, a scriptwriter and playwright.

Although the director’s task was not to create a documentary (even the movie characters’ names were changed), he found it impossible to avoid an endless circle – ‘the hijackers’ were, are, and always will be the main theme and will be subject to continuous political speculations. It gave grounds to many questions that are still unanswered and is still a subject of fierce debates, equally as it was then, 34 years ago.

The few days prior to the wedding, the wedding party itself and the plane hijacking are the three major episodes around which everything in the film develops.

It doesn’t matter whether you are watching the final scene where the law-enforcers are escorting rioters – all covered in blood and white-faced with fear; or the bride and groom – dancing happily amidst the wedding party noise and whooper-dooper; throughout the film you feel as if locked in a gloomy, portentously sweltering environment.

Whether it be stylistically and/or emotionally, the film strongly conveys the message that you memorize those infantile, confident faces with courage and fear flashing across them from time to time. But without realizing its context, it will just remain a story of guys who tried to hijack the plane. They just tried and that’s it.

It feels like there is something missing and that’s probably due to the fact that trimming those vast, multi-layer materials down to a single fragment, hijacking, makes it almost impossible to analyze it as a whole, to see the broader picture.

Who is actually the hostage there? The one who is trying, through violence, to free themselves of clutches of life, or the civilian who finds himself in captivity on board a plane? Although this question remains ambiguous in the movie title, either the accelerated infantilism, the characters’ panic-driven fear or the conversation between Tina and Nika’s mother at the end of the film, make you realize that the authors couldn’t completely distance themselves from the characters. Despite their attempts to gently walk along the sharp edge of history, a mythical tint could still be felt in the film.

Recalling one moment where the plane is forced to land in Tbilisi. The hijackers refuse to release the hostages. Two hostages are dripping with blood and there are some other wounded people as well. Then they choose one of the hostages and send him outside to report the situation. Some monotonous sounds could be heard in the plane. Suddenly, you see the small hands of a hostage boy on an airline seat who is playing ‘Nu, pogodi’ (‘I’ll get you!’, a soviet-time portable game), collecting eggs in a basket. There are tears running down his face, gushing from his eyes.

But the most memorable moment is the scene of the next day at the wedding. It’s Nika’s house. It’s getting dark. The guests are in the room, celebrating the young couple’s wedding and seeing them off to the airport. Nika and Tina are setting out for their honeymoon, leaving for Batumi. When Nika leaves the house, you could see his face, as if he is pondering over something and then…he turns around and returns home. He goes from one person to another, kissing, pinching, tickling or telling them something – he is kidding around and even clambers under the table. The camera is following him, focused on each emotion. There is background music or, to be more precise, some cacophony which resembles the sounds coming from a rehearsal room, something chaotic and unsmooth. As you watch that episode and hear that noise, you are gripped by an unspeakable feeling of anxiety.

I have not seen such an ideally created claustrophobic environment and the Soviet Union so close up for a quite long time. The credits for this certainly goes to Kote Japaridze, a production designer, and Vladislav Opeliants, a cameraman. The film cast is also good, especially Darejan Kharshiladze starring as Nika’s mother. Also, the ambiance; a feeling that doesn’t let you relax even for a second throughout the entire 103 minutes.

‘Hostages’ is a drama. A drama without catharsis.