Baku and Absheron water supply: 30 reservoirs, 95% promises and old risks

Water supply in Baku

The new State Programme covering 2026–2035 aims to modernise drinking water supply, sewage and stormwater drainage systems in Baku and on the Absheron Peninsula.

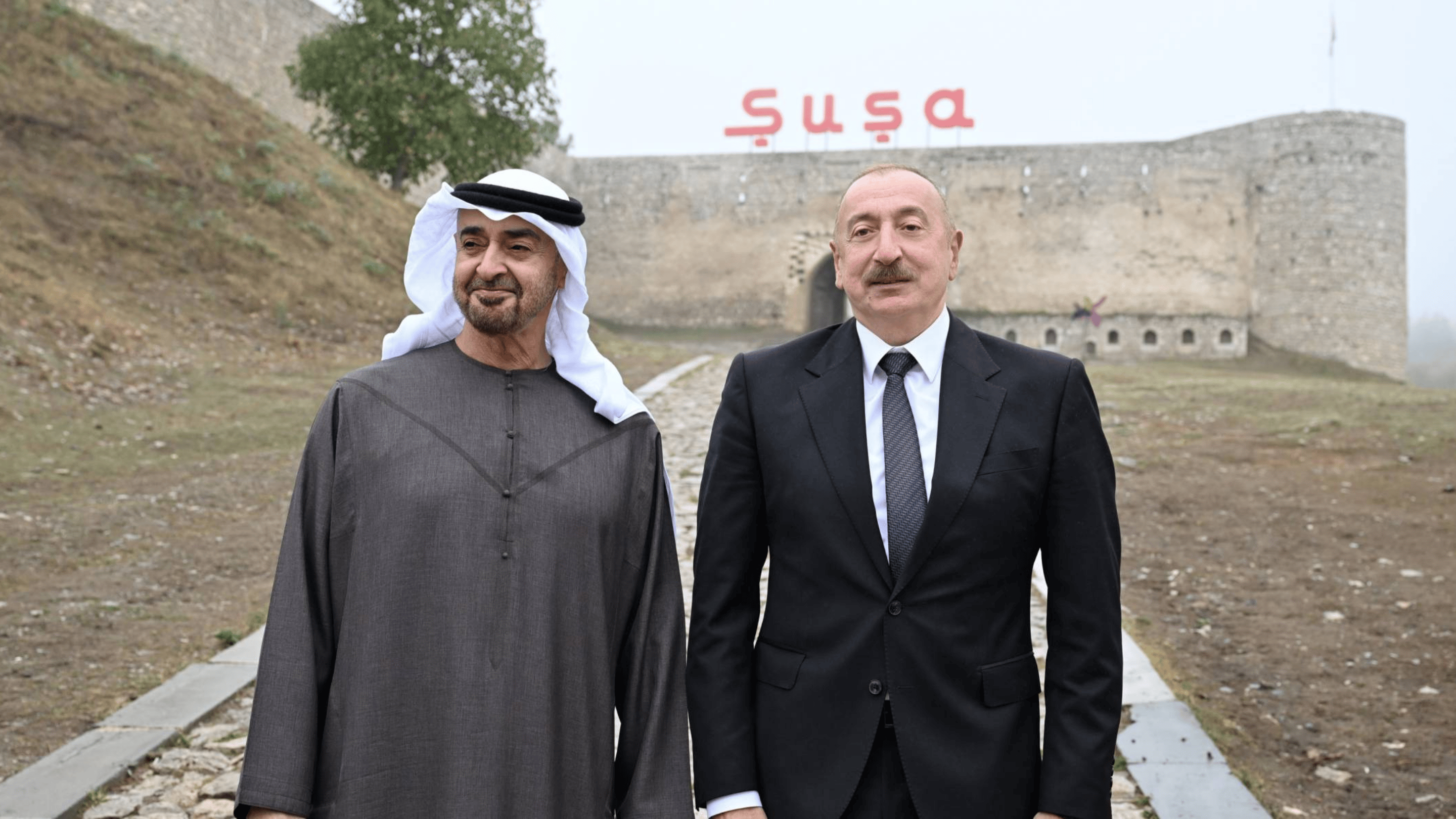

The programme was announced by President Ilham Aliyev on 12 January and covers Baku, its surrounding settlements, the country’s second-largest city Sumgayit, as well as the Absheron Peninsula as a whole, encompassing a total of 64 населённых пунктов.

The programme’s core objective is to ensure the region has a stable and uninterrupted supply of drinking water. To achieve this, authorities plan to build around 30 new reservoirs and refurbish more than 200 km of existing trunk pipelines and distribution networks.

As a result, the share of residents in Baku and the Absheron Peninsula with round-the-clock water supply is expected to rise from the current level of about 70% to 95%, while access to sewerage services is set to increase from 50% to 95%. The programme also aims to significantly reduce water losses from the current 40–45% and to achieve full metering coverage across the water supply system.

Technical infrastructure and supply resilience

The technical component of the State Programme envisages large-scale infrastructure projects. A key priority is the construction of new water reservoirs, with around 30 planned, representing a significant expansion of the region’s capacity to store and distribute water resources.

At the same time, trunk water pipelines and distribution networks are set to be upgraded. Replacing outdated pipelines is intended to reduce water losses across the system.

Stormwater and wastewater systems also feature prominently in the programme. For residents of Baku, the problem is well known: during heavy rainfall, streets are often flooded and traffic is effectively brought to a standstill.

To address this problem, the programme provides for the construction of new stormwater collectors on 30 streets in Baku. These are expected to ensure effective drainage of rainwater and significantly reduce the risk of flooding across the city.

In addition, wastewater treatment infrastructure will be upgraded. The stated goal is to achieve full treatment of effluent discharged into the Caspian Sea, with particular emphasis on modernising and expanding the capacity of the Hovsan Aeration Station.

Finally, Azerbaijan is building its first seawater desalination plant. A pilot project has already been launched to improve water supply on the Absheron Peninsula, converting water from the Caspian Sea into drinking water.

The plant will be fully financed through foreign investment and is expected to have a processing capacity of around 300,000 cubic metres per day—equivalent to roughly 100 million cubic metres a year. Officials note that desalination technologies will provide the Absheron region with an additional source of water.

Caspian Sea water is less saline than open-ocean water, and after treatment using modern membrane technologies it can be made suitable not only for drinking, but also for technical and irrigation purposes.

Social impact and urbanisation pressures

One of the most significant outcomes of the new State Programme is expected to be social change, with a positive effect on residents’ quality of life. At present, only around 70% of people in Baku and on the Absheron Peninsula have uninterrupted, round-the-clock access to drinking water, while the remaining roughly 30% are forced to live according to a daily water supply schedule.

This means that hundreds of thousands of residents receive water in their homes only at certain hours, are compelled to install additional storage tanks, or to carry water manually. If the programme is fully implemented, continuous water supply coverage is expected to reach 95%, meaning that virtually all residents of the capital and the Absheron region would have access to clean water 24 hours a day.

At present, sewerage services in the region cover only about half of the population. As a result, in many settlements and newly built residential areas, wastewater is either discharged into open channels or accumulated in underground pits, creating serious environmental and public health risks.

Expanding the sewerage network to 95% coverage would fundamentally address this problem. Once the programme is completed, almost all населённые пункты in Baku and on the Absheron Peninsula are expected to be connected to a centralised sewerage system.

Urbanisation pressures in the Baku region have risen sharply over recent decades. As the country’s main economic hub, the capital continues to attract people in search of jobs and access to services. As a result, the population of the Baku–Sumgayit–Absheron metropolitan area has grown significantly since the 1990s and, according to unofficial estimates, has approached 4.5 million—around half of the country’s total population.

Such rapid population growth and industrialisation have dramatically increased demand for water. On the Absheron Peninsula, new residential developments, factories and plants require both drinking and technical water. The State Programme is widely seen as having been designed with this mounting urbanisation pressure in mind.

The quality and reliability of water supply are also key factors directly affecting social wellbeing. In a number of outlying villages and settlements around Baku, residents have complained for years about the lack of adequate access to drinking water. For example, in Nardaran and some neighbouring communities, tap water is virtually unavailable during the summer months, forcing residents to rely on well water or supplies delivered by water tankers.

In some areas, poor water quality has led residents to install improvised filters and carry out additional treatment at home. Under the programme, special attention is expected to be given to these water-scarce areas.

Expanding the centralised network and constructing new reservoirs should help ensure a stable water supply for more remote settlements as well.

Corruption risks

One of the potential risks in implementing such a large-scale infrastructure programme remains corruption and project delays. Previous experience in Azerbaijan suggests that a number of major water projects ended up costing far more than originally planned and delivered limited efficiency.

For example, between 2007 and 2010, the construction of the Oguz–Gabala–Baku water pipeline, financed by the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan, cost 779.6 million manats (around $460m). Independent experts estimated that the project’s real cost should not have exceeded 300 million manats (about $177m), indicating that expenses were significantly inflated and surplus funds misappropriated.

At the time, such irregularities went unpunished, and the public never received sufficient information about how the allocated funds were actually spent.

This problem is not limited to a single project. For many years, responsibility for water supply and sewerage lay with Azersu, the state-owned company in charge of water supply and wastewater services in Azerbaijan, which has repeatedly come under scrutiny over opaque operations, heavy financial losses and excessive administrative spending.

According to a 2020 report by the Chamber of Accounts of Azerbaijan, despite receiving 401 million manats (around $206m) in state support, Azersu paid just 10 million manats (about $5.6m) in taxes to the budget—meaning the funds it received from the state exceeded its tax contributions by a factor of 40.

Moreover, despite accumulating losses exceeding 7 billion manats (around $4.1bn), the company went on to build an expensive office building in Baku. These facts point to a systemic issue of transparency in state-owned companies and a lack of safeguards to ensure the efficient use of public funds.

Experts also stress that public procurement in Azerbaijan is often conducted under conditions of merely formal competition and according to pre-determined scenarios, significantly increasing the risks of inequality and corruption.

Risks of delays

The timely and high-quality execution of works will be critical to the successful implementation of the State Programme. In the past, a number of infrastructure projects were affected by delays caused by bureaucratic obstacles, contractors missing deadlines, or repeated revisions of project design and cost documentation, with planned timelines frequently overrun.

The new water programme has been launched with a clearly defined goal of completing all works by 2035. It is expected that all planned measures will be fully implemented within this period. At a meeting, President Ilham Aliyev stressed that the programme is рассчитана roughly for ten years and that, according to preliminary estimates, this timeframe is sufficient—but not a single day of delay should be allowed.

He also said that oversight would be strict at both government level and within the Presidential Administration, and that officials falling behind schedule would be held accountable.

International experience: lessons from Israel and Saudi Arabia

In developing the State Programme—and particularly in the search for innovative solutions to water supply challenges on the Absheron Peninsula—the authorities examined the experience of various countries. Of particular interest to Azerbaijan are models from states that have achieved success despite severe water scarcity, notably Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Israel’s water management model is regarded as one of the most efficient in the world. Despite extremely low rainfall—averaging about 250 mm a year—the country has achieved a technological breakthrough in water resource management, turning a chronic constraint into a strategic advantage.

To draw on this experience, Azerbaijan has stepped up cooperation with Israel in recent years. In 2022, the Azerbaijan Investment Company signed a memorandum of understanding with IDE Technologies, a globally recognised leader in desalination, on the construction of a Caspian Sea water desalination plant.

Since then, Israeli specialists have been working on transferring technologies to help address Absheron’s water challenges. In September 2025, at Baku Water Week held in Baku, a representative of Israel’s national water company Mekorot, Barak Graber, said that a tender had been conducted to attract the world’s best desalination technologies and that an optimal technological solution had been selected.

The process took the form of an international competition involving Israeli firms as well. As a result, in the tender for the Caspian Sea desalination plant project, IDE placed second, submitting proposals at various stages of the selection process.

Saudi Arabia is another important international example in the water sector. Together with other Gulf states, it currently accounts for more than 44% of global desalinated water production.

The kingdom has also succeeded in turning its engineering firms into global brands. In particular, ACWA Power, a Saudi water and energy company, is now implementing more than 90 projects across 13 countries, with the total value of its investment portfolio approaching $97bn.

It was ACWA Power that won the international tender to build the first desalination plant for Baku and the Absheron Peninsula. In 2023, an agreement on the project was signed between the State Water Resources Agency of Azerbaijanand ACWA Power. The plant is planned to be built at the Sumgayit Chemical Industrial Park.

The project is valued at around $407m, with a planned capacity of 300,000 cubic metres of water per day, or roughly 110 million cubic metres a year. Under the agreement, ACWA Power will design and build the plant, fully finance it through foreign investment, and operate the facility for 25 years, selling the produced water to the Azerbaijani side. After this period, ownership of the facility will be transferred to the state.