Childhood sold away

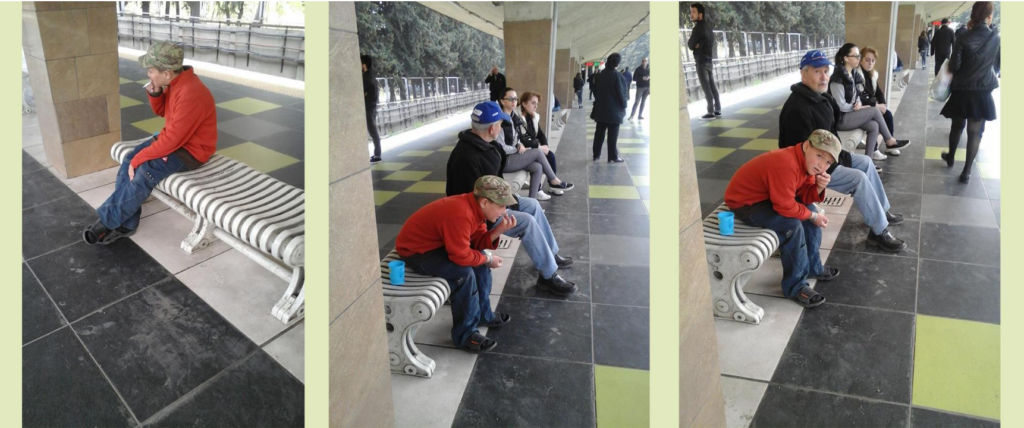

Many children pace to and fro in Tbilisi Metro cars. However, this particular boy is stuck in my mind. He was giving out small icons. He is about nine, but judging by how he smokes a cigarette, one may come to think he is much older.

“Don’t you sell icons any longer?” I nod at the empty glass where he used to collect alms.

“No, now I sing,” The boy smiles. “Singing pays better. I have already collected GEL 35 since the morning!”

A train arrives and its doors open. The boy enters a carriage and goes into song. A minute later another beggar sits down near me on the bench. She empties a plastic glass with coins on her palm and begins counting them. A child on her knees tries to reach the coins, spread out on her hand. “How old is he?” I ask when she has finished counting, but the train has not come yet.

The woman answers easily in detail, almost with a pleasant tone. “A year and four months. He is the youngest. There are three more children waiting at home. The eldest one is five, the middle child is three and the youngest one is two years old. She receives state benefits, but the amount is so scanty that she has to beg.

“I learned some details of this ‘work’: they work the whole day, from 8.00 a.m. till almost midnight. She has to hire a baby-sitter and pays her GEL 10 daily, which makes up one third of her earnings. If a women without children begs, she earns much less. Therefore, the ones who have no children, ‘lease’ them, which costs GEL 15-20 daily.

Begging became a serious problem in Georgia in the 1990’s. Gradually, more and more young people begin panhandling; at present there are many children who are doing this. The first time the state realized the scope of the problem was roughly 20 years after poverty had become a mass phenomenon.

The first serious program for street children was only established in 2009. Active groups, consisting of social workers, psychologists, administrative officials and teachers, surfaced in Tbilisi as a result of this program – they met with street children, established contact with them, tried to gain the children’s trust and persuaded them to come to one of the day centers that had been opened in Tbilisi as part of that program.

The day center is a place where a street child can get some food, sleep and take a shower. However, there is a major flaw in the system – the day care center’s services are unavailable for officially unregistered children. Very often it is impossible to register children as many of them have no documents.

As prescribed by law, a child’s parents or legal guardians are supposed to appeal to the Georgian Justice Ministry to register a juvenile. Social workers had to establish contacts with families, assist them in obtaining a birth certificate and an ID card, but it takes a lot of time and does not always have a positive outcome. A new program, established in 2013, did not solve the problem of undocumented youth either.

Nevertheless, governmental institutions are optimistic. The Ministry of Justice of Georgia has drawn several legislative amendments. In this bill, street children would be granted “homeless status, while social service workers would be entitled to appeal to the appropriate agencies of the Georgian Ministry of Justice to provide a homeless child with documents.

Will this really change the conditions of street children? Children do not go into the street of their own will, but rather at the beckoning of or pressure from parents, next of kin and acquaintances. Human rights activists believe this bill is not going to remove the problem. In their opinion, the problem should not be considered in the socio-economic sphere, but rather in the judicial one, as a crime that is being committed.

According to Anna Abashidze, the head of the NGO group ‘Partnership for Human Rights’: “The amendments that the Parliament is going to consider, are not going to solve the principal problem. Let’s imagine that I am a victim of domestic violence.

The state takes me to a shelter, it promises to wine and dine me, but it does nothing to my abuser. I don’t understand why we should be like this with abusive parents, who cast their children out onto the streets and make them beg. It is equal to murder.”

“Instead of wasting two years on rectifying the documents’s issue, the government should mobilize law enforcers to focus on the crimes against children,” Anna Abashidze believes.

“I am sure the situation will change for the better as soon as some cases are dealt with successfully,” she said.

A social worker determines whether a family really needs money and that is the reason why a mother takes to the streets with her child to beg or the child is the victim of violence and is forced to ‘work’ in the streets. After the legislative amendments are passed, a social worker will be able to decide to immediately separate a child from an abusive parent.

In this case any person who abuses a child would be considered an aggressor. At the same time, human rights activists have reasonable questions – why should a social worker, so overloaded with other duties, be given more tasks? In most cases, it is hard to prove that children are exploited. Why are law-enforcers so complacent? Why are people who deserve the strictest punishment prescribed by the law not deprived of their right to be a parent? There are no answers to these questions because the state still has no desire to design an effective system of assistance for those who need it most.