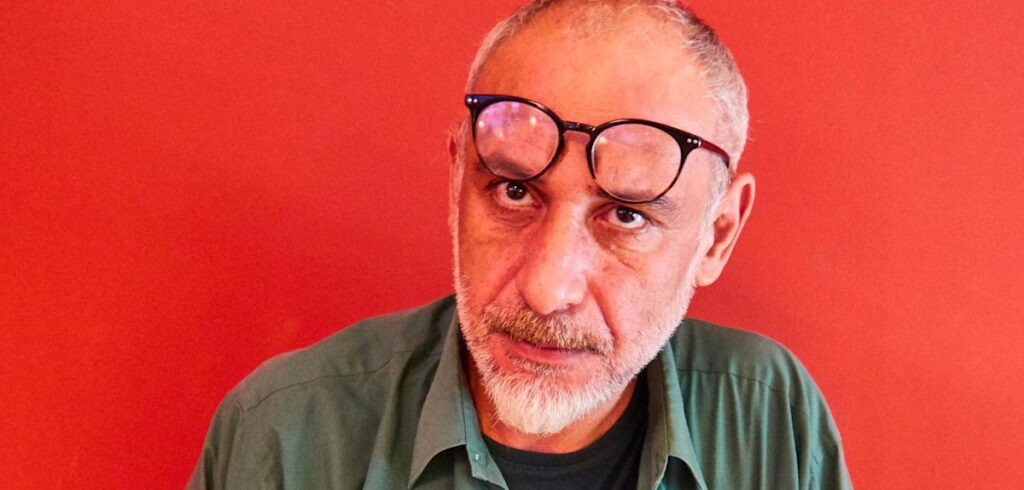

Georgian poet behind bars: protest and arrest of Zviad Ratiani

Zviad Ratiani poet case

Zviad Ratiani, a well-known contemporary Georgian poet and active participant in pro-European protests, has been sentenced to two years in prison.

Ratiani became the third political prisoner in the country arrested for slapping a police officer.

However, his case is unique. Ratiani essentially went to prison voluntarily—as an act of protest.

On 9 October 2025, the day his sentence was handed down, the poet said in his final statement that his slap to the head of the patrol police was a symbolic and deliberate act, inspired by teacher Nino Datashvili and journalist Mzia Amaglobeli.

Journalist Mzia Amaglobeli has been sentenced to two years in prison for slapping the head of the Batumi police.

Initially, Ratiani and Amaglobeli were charged with assaulting a police officer, a crime carrying a sentence of four to seven years. However, the charges in both cases were later reduced to “resisting a police officer.”

Another woman, teacher Nino Datashvili, also faces possible imprisonment for allegedly attacking a bailiff at the Tbilisi City Court. Witnesses, however, claim that Datashvili’s actions were in response to violence by the bailiff.

Poet Zviad Ratiani was arrested on 23 June 2025, on the 208th consecutive day of protests in Tbilisi outside the Georgian parliament.

Footage from surveillance cameras, recorded before the arrest and released by the pro-government channel Rustavi 2, shows Ratiani calmly speaking with a man dressed in black standing near a police patrol car, before suddenly striking him in the face. He was arrested immediately afterward.

The Prosecutor’s Office stated that Ratiani “struck Teimuraz Meshvelashvili, head of the Didube-Chughureti patrol and post service.”

On 25 June 2025, when Tbilisi City Court judge Arsen Kalatozishvili ordered Zviad Ratiani into pretrial detention on the grounds that he might flee, Ratiani told the court:

“I am not going anywhere, because every evening I need to be on Rustaveli, and since my term of detention is approaching, I must get on with my work.”

Protests, beatings and emigration

Zviad Ratiani had long been an active critic of Georgian Dream and had been subjected to administrative arrest twice.

The poet was among the first activists brutally beaten by special police units during the November 2024 protests.

A widely circulated video shows a protester in bright clothing being engulfed by a massive wave of police and special forces. Friends identified the protester as Ratiani by his orange jacket.

After his arrest, Ratiani was severely beaten. A medical report documented multiple fractures and injuries: a broken nose, a knocked-out tooth, bruises and abrasions across his body.

However, the judge did not consider these injuries sufficient grounds for his release. Ratiani was found guilty of petty hooliganism and disobeying a police officer and was sentenced to eight days of administrative detention.

The persecution of Zviad Ratiani did not end there. After his release from prison, four unidentified individuals ambushed the poet near his home and beat him.

But Zviad Ratiani had been a target of Georgian Dream long before the 2024 protests.

In December 2017, during a police check (at a time when officers were conducting nightly raids on the streets of Tbilisi), Zviad Ratiani was stopped by police. Officers told the poet they did not like the colour of his jacket, arrested him again for disobeying the police, and beat him severely.

Ratiani then spent ten hours in prison. After his release, he spent several months unsuccessfully trying to be recognised as a victim and to have the alleged crime committed by the police investigated.

In September 2018, Ratiani emigrated to Austria, but returned to Georgia several years later. Despite previous police violence, he regularly participated in pro-European protests in Tbilisi, taking to Rustaveli Avenue every evening in front of the parliament building.

Imprisoned poet without paper and pen

For nearly four months before his sentence was announced, Ratiani’s defence petitioned at every court hearing to change his pretrial detention. Each time, however, the judge kept the poet in custody.

Ratiani was placed in a cell with other prisoners of conscience.

“Don’t worry about me, I’m strong and will become even stronger. And know that so far I have done everything right. First, they put me in a cell instead of a rehabilitation ward. Then they placed me in a cell with [political prisoners]. This is not a cell, it’s a revolutionary committee headquarters. We live four to a cell: Gio Akhobadze, Nikusha Kacia, Tornike Gishadze, and I. It’s cramped, but clean,” he wrote in one of his letters from prison.

Two of Ratiani’s cellmates, Giorgi Akhobadze and Nikusha Kacia, had been arrested on drug possession charges and are now free. A judge ruled that there was insufficient evidence in their case.

“I am a much more privileged parent, because I am in prison myself, not my child. Your fate is much harder, and your courage far more admirable,” he wrote to Marizi Kobakhidze, the mother of his cellmate Tornike Gishadze.

Ratiani continued writing poetry in his cell. However, by early October, he reported that he had been unable to obtain paper and a pen for three weeks.

Sentencing and poet’s final statement

On 9 October 2025, the day of the sentencing, the courtyard, lobby, and courtroom of the Tbilisi City Court were filled with the poet’s friends and supporters. Only a few of those who wanted to enter the courtroom were able to do so; the rest waited outside for the announcement of the verdict.

Zviad Ratiani delivered an emotional final statement, which was not recorded on video, as the Georgian Dream government had banned photo and video filming in court over the summer.

Ratiani urged those present to accept his sentence calmly and not to argue with the court bailiffs.

He also spoke at length about his motivation:

“The first thing I must start with is the story itself [of the attack]. First of all, there is the footage you have seen. Of course, it is not my role to judge how serious this attack was. Talking about it would be a waste of time.

These people [present here] do not need explanations, and you [the judge] probably do not want to understand me.

So I will move on to the circumstances and motivations that led me to take this step. These are emotions that are not governed by law… emotions that make us human.

Of course, in a normal [political] environment, no one would even think of hitting or assaulting a [police officer]. The general misfortune, or rather absurdity, is that one person (Ivanishvili — JAMnews) and his team have turned everything in this country upside down.”

Ratiani mentioned his numerous past encounters with police and said that, if hatred had motivated the strike, he would have chosen one of the officers who had beaten him repeatedly. He added that he knows almost all of them and had even met some at protests.

But, he said, the strike was not out of hatred, but guided by conscience. Before hitting, he verified the identity of the officer, who turned out to be a chief (Mzia Amaglobeli was also charged with resisting the police chief — JAMnews).

“Of course, the strike was symbolic. I will not go into the history of symbols, but move on to what caused it.

I do not like pathos. I have never liked it, and it irritates me in my daily work, but I am sure you know that in the Georgian language, as in many others, there is a word — conscience.

And that conscience truly disturbed me while I slept peacefully in my bed, ate at home, worked on texts no one cared about, surrounded by the care of a beloved woman, spent time with my extraordinary children… while people their age, and even younger, were being sacrificed by police to an old man obsessed with money and power, who openly serves the enemy.

I witnessed this, and it troubled me — not because I am better than others… but because this is a struggle. We fight for our interests, those on the other side fight for theirs. That is how it works.

I do not consider the slap I delivered something to be proud of, nor a crime — with the caveat that we are in an absurd situation.”

Ratiani also mentioned Mzia Amaglobeli and Nino Datashvili. He said that after Amaglobeli’s arrest, they witnessed her “ritual killing” every day. Then Nino Datashvili was humiliated in the same way, and later even faced attempts to be forcibly sent to a psychiatric hospital.

“Probably no more than two months before my arrest, the publication Batumelebi asked me to write a letter about Mzia for the newspaper. It is an ordinary request, since I am a person tied to the pen and often receive such requests on various topics.

I wrote something, and then felt the pang of conscience again. When I finished, I went out onto the balcony and was initially very pleased to have met the deadline. All three of my cats followed me, and I smoked, thinking shyly that I, such a ‘big’ man who has seen so much in my years, sat down and wrote this, and then I would go out onto Rustaveli Avenue and most likely be fined again. And that is all I am.”

According to Ratiani, he now feels morally superior. He added that he does not like the story he told, but it is true, and he is on the right side of this struggle.

He also stated that whatever sentence he receives, his fate will be far easier and more desirable than that of those who serve or silently condone injustice.

“I am full of strength; I can still write in health and in illness — more so in illness. But I do not lose hope,” Zviad Ratiani concluded.

Journalists recorded the poet’s final words by hand and circulated them in the media.

“There will come a time when our children and yours (judges, prosecutors, servants of the regime) will study this speech in school,” social media users commented on the poet’s final statement.

Zviad Ratiani poet case