From Russia to the West, from the West to Russia

Since gaining their independence, the former Soviet republics have been facing a choice: whom are they close to – to the West or Russia? Unlike Kazakhstan and the Central Asian countries, that are less concerned about this issue, the states, located in the European part of the post-Soviet area, are always under pressure.

The Baltic States have made a clear choice in favor of integration into Europe. Russian has failed to rein them in. This is not the case with Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Russia is doing its best not let these countries go. The West, in turn, is doing everything possible to knock Russia out of this huge region.

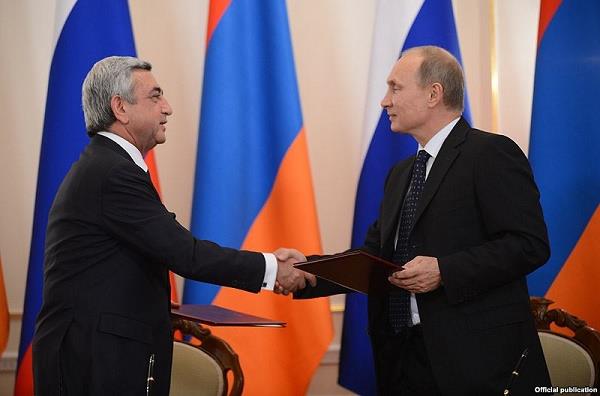

Belarus and Armenia are Russia’s allies. They are members to all political and economic organization, set up by Russia. At the same time, the West is also flirting with them. For example, it does not give up on partnership with Armenia within the framework of NATO or the EU rapprochement program. With regard to Belarus, a number of sanctions were lifted in 2015, though earlier, President Lukashenko had been called ‘Europe’s last dictator.’ But hardly anyone in Washington and Brussels has any illusions about full-fledged cooperation with Yerevan and Minsk.

In May 2009, the European Union’s ‘Eastern Partnership’ program was approved, the key stated goal of which is to develop integration ties between the EU and six countries of the former USSR: Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia. This program caused Russia’s indignation and triggered tough opposition in the post-Soviet area. The attempts of these countries’ rapprochement with the West has led, for example, to the Ukrainian conflict and Moldovan crisis. Before that, Georgia also experienced a shock: there was a war with Russian in August 2008, as a result of which Moscow recognized the independence of two Georgian regions – Abkhazia and South Ossetia. About Armenia and Belarus it has been written above. Among these six countries, Azerbaijan has turned out to be in a special situation.

Since gaining its independence, the hydrocarbon-rich Azerbaijan has given preference to the pro-Western vector of development. Despite Russia’s opposition, Azerbaijan signed a contract with the foreign companies’ consortium, built the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan and brought huge volumes of Caspian oil to the world markets. Now, the construction of a gas pipeline to southern Europe is underway, that makes Moscow aggressively jealous. Azerbaijan has become one of the key stakeholders in ensuring Europe’s energy security.

In the political sphere, Baku has also opened to the West. In addressing its main problem – the Karabakh conflict – Azerbaijan relied on the mediation of European and U.S. partners. Baku is actively involved in the fight against international terrorism; it plays an essential role in securing peace in Afghanistan; in 2012-2013, it was a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council, representing the Eastern European region. Baku welcomed the ‘Eastern Partnership’ with enthusiasm. The sides considered possible signing of an association agreement. But suddenly everything changed.

‘Suddenly’ was in 2012, when Baku hosted the ‘Eurovision’ song contest. Having spent hundreds of millions of dollars on holding the contest, Azerbaijan expected the West’s rapturous attitude to its socio-economic development. However, on the contrary, the country, turned out in the focus of the international human rights organizations’ attention, who have accused the Azerbaijani authorities of persecution of their political opponents. Baku negatively reacted to this and the West was accused of applying ‘double standards’.

There were allegations about destructive activities of the western institutions in the settlement of Karabakh conflict. The west was accused of the attempts to support a ‘Facebook revolution’, like those that occurred in the countries of the Greater Middle East. The supporters of the pro-Western integration were referred to as the ‘fifth column.’ A number of human rights activists and journalists were arrested and detained on different charged. Representatives and representative offices of several international organizations, especially the U.S.-funded ones, were ousted from Azerbaijan.

After the Ukrainian Euromaidan, when Russia responded by annexation of the Crimea and the hostilities in Donetsk and Lugansk regions were launched, there was even greater breakdown in relations between Azerbaijan and the West. Baku decided that Putin’s Russia should be reckoned more and that the Kremlin should not be irritated, and also, that the West’s tactics in supporting the opposition should be also taken into account.

Azerbaijan’s controversy with the West reached its peak in 2015, when European leaders refused to take part in the opening ceremony of the first European games in Baku, as well as due to the OSCE’s refusal to send its observers to the parliamentary elections in Azerbaijan. As of the end of 2015, there were about 100 political prisoners in Azerbaijan, many of whom were recognized as prisoners of conscience and none of them was acquitted, as it was continuously demanded by the international human rights organizations. Russia’s aggressive policy in Ukraine and the Middle East added fuel to the fire, and the pro-government media and politicians in Azerbaijan started blaming the West for many problems, making curtsies towards Russia.

Azerbaijan turned out in an ambiguous position. For two decades, the country was strengthening partnership with the West. Azerbaijan’s economy is tied to the energy resource supplies to the West. The country was step-by-step getting closer to Washington and Brussels, including in the military sphere. Azerbaijan’s strategic ally is Turkey, which is in an acute phase of conflict with Russia. But, on the other hand, one has to act with regard to Moscow, and, furthermore, the country’s leadership is eager to get the Kremlin’s political support in preventing various ‘Facebook revolutions’ or ‘South Caucasus Spring’.

In view of the fact, that Russia has assumed a role of key actor in preventing DAISH on the post-Soviet area, without taking into account the Kremlin’s views, it is getting more difficult for Baku to maintain a foreign policy balance, in general. For example, Azerbaijan, which is through thick and thin sharing Turkey’s position, does not officially respond to Russia’s launch of ballistic missiles from the Caspian Sea area, which was previously declared the ‘Sea of Peace’.

Azerbaijan’s further foreign policy orientation seems vague. The leadership would prefer to promote a balanced position, equally distancing itself from or equally getting closer to both, the West and Russia. However, it is hardly possible in the short run. At present, there is more forced partnership with Moscow, which is always like playing with fire. Problems in the human rights sphere, unwillingness to concede to international institutions and fear of the ‘revolutionary spring’, are preventing Azerbaijan from taking another step towards the West.