QR codes on graves in Azerbaijan "tell" the life stories of the deceased

Graves with QR Codes in Azerbaijan

A typical day at the Mardakan Cemetery on the periphery of Baku, Azerbaijan. On one side, people come to visit the graves of their loved ones, moving between rows with flowers in their hands, while on the other side, workers are busy preparing tombstones for new graves.

Hundreds of marble tombstones contain brief information – names, surnames, dates of birth, and death.

- “Why leave people without jobs?” – Azerbaijani taxi drivers unhappy with new regulations

- In Azerbaijan, 25 IDp families await state aid

- Stray dogs in Azerbaijan – how to solve the problem?

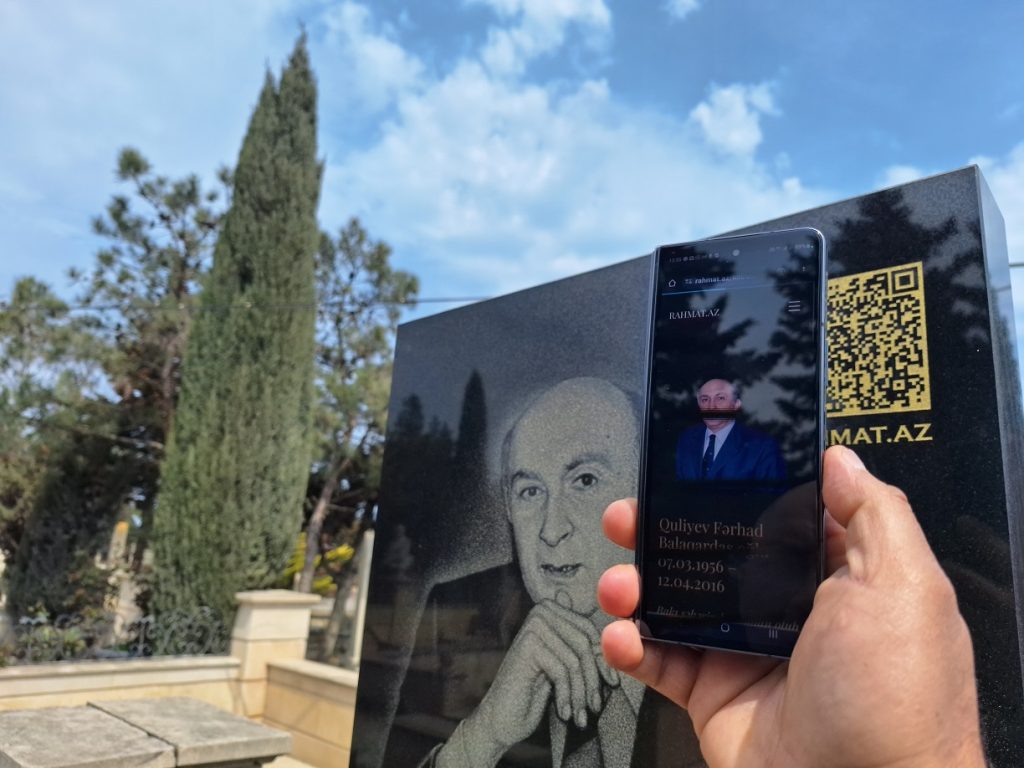

“Look, in the front row, you’ll see graves with QR codes,” Zaur Guliyev points out the tombstones that stand out from the others.

These graves in two rows belong to soldiers who died in the first and second Karabakh wars. QR codes are engraved on their tombstones. Scanning the code leads to rahmat.az website, where you can read the life story of the deceased: who they were, where they were born, what they did, how they died, and so on.

“As long as the memory is preserved, a person will live”

Zaur Guliyev is the author of the idea and the founder of this website.

“One day, I came here to to visit my father’s grave. On the same day, a woman came to her son’s grave. She cried so much that her voice could be heard throughout the cemetery. I couldn’t bear it, approached her, and offered my condolences. She started telling me about her son.

He was 25 years old and a very religious young man. The mother spoke about how her son saw his future, what he dreamed of, and how kind he was to people.

One day, the family unexpectedly found out that the boy had cancer. The illness was discovered very late, and there was no hope for his recovery.

Listening to the woman, I thought that everyone should hear these stories. So many stories lie beneath these stones, which from the outside look like simple graves. As long as the memory is alive, the person will live,” Zaur recalls the day his idea was born.

On the same day, he met with his friend Elshan and shared his thoughts. Zaur calls it a “virtual cemetery.” His friend also liked the idea, and without hesitation, agreed to participate.

Since Elshan works in the IT (information technology) field, he was responsible for the technical work related to the QR code and the website. Zaur himself started organizing the work. He purchased the necessary materials (marble, etc.) for engraving the QR code on the tombstones and handed them over to the craftsmen for preparation.

All the content on the website is translated into Russian and English. Geolocation of graves can be added if necessary.

Information in the “Shehids” [an Azerbaijani word for the war victims – JAMnews] and “Historical Figures” sections is publicly available on the website. Information about “ordinary people” can only be seen by scanning the QR codes on their graves.

Father’s story

“We made the first tombstone with a QR code for my father,” Zaur says.

“My grandfather was a military man, and, by the way, I followed in his footsteps. I was in the military myself until I retired three years ago.

When my father was a child, life was difficult for everyone in Azerbaijan. Everyone struggled with poverty and looked for ways to support their families. Despite the challenges, my father pursued higher education and became a lawyer. It was a tremendous effort at the time.

After that, my father worked for many years as a detective on particularly important cases in the Ministry of Internal Affairs. He was a very caring person. I was the only son in the family, and I grew up surrounded by my father’s care. Now I understand better than ever that the most important thing for a child is parents who always support them,” he says about his father.

QR codes have been applied to the graves of 46 people, 34 of whom are shehids

So far, Zaur has implemented his idea only in three cemeteries in Baku. In the future, there are plans to popularize QR codes throughout the country. The first orders from regions have already been received.

At this point, QR codes have been applied to the graves of 46 people. Thirty-four of them are the graves of soldiers who died in the Karabakh war. Zaur says they have been fulfilling orders from shehids’ families free of charge. For other clients, the fee for the service is 50 manats [approximately $29]. The service includes creating a page on the website in the name of the deceased, posting three photographs, one video file, map data, and generating a QR code.

Upon receiving an order, he first learns about the deceased’s story. He says it’s like getting to know a new person, but the difference is that the person doesn’t tell their own story.

Among the stories he has heard so far, there are several that will stay with Zaur forever. One of them is the story of Gamar Khanim [Khanim is a respectful term for a woman, added in Azerbaijan to names – JAMnews].

Gamar Khanim was born in 1889 in Baku.

“Relatives of Gamar Khanim contacted me and asked to engrave a QR code on her grave. Her story fascinated me a lot. They say she was the daughter of one of Baku’s millionaires. In her youth, she fell in love with a boy from a poor family, but her family objected to such a marriage. She gave up her family’s wealth and eloped with her beloved. They got married. Their life was full of hardships. But they say they still lived very happily. After all, they loved each other,” Zaur smiles.

“My daughter is not interested in this”

Grigory Kochnev (Grisha), a close friend of Zaur’s, was one of the first to order a gravestone with a QR code. He asked to prepare a QR code for the grave of his grandfather, Kochnev Grigory Ivanovich, in whose honor he was named.

“Zaur told me about this idea he had, and I immediately said I wanted to do it for my grandfather. Because it’s about memory.

Let me try to explain: I have a 14-year-old daughter, and when we go to the cemetery to visit the graves of our relatives, I feel like she’s not interested. Because she doesn’t know these people. They either died before she was born or when she was very young. Even adults forget the past.

His grandfather, Grigory Ivanovich, was born in Tsarist Russia in the late 1880s. ‘When there was a major food shortage in Russia on the eve of the First World War, my grandfather was a cart driver and transported asphalt.’

“Seeing that it was becoming difficult for him to earn a living there, he decided to move to Azerbaijan. My grandfather thought of building a new life for himself here. Initially, he arrived in Buzovna, and a few years later, he settled in Mardakan (a district of Baku). Here, he met my grandmother, and they got married. My grandmother is also Russian but was born and raised in Azerbaijan. Since then, our family has settled here – in Mardakan.”

Grisha, 55, has a daughter and a son. He and his wife met and got married here, in Mardakan, as well.

“We have relatives in Russia. I photographed my grandfather’s grave with the QR code and sent it to them; they liked it very much. I will do this for other relatives as well. I don’t want the history of our family to be forgotten,” says Grisha.

“Thank you, that’s exactly what I’m talking about. This initiative is aimed at ensuring that our history and memories are not forgotten,” concludes Zaur.