Thirty years have passed. Do Abkhazians and Georgians need a new war? Opinion

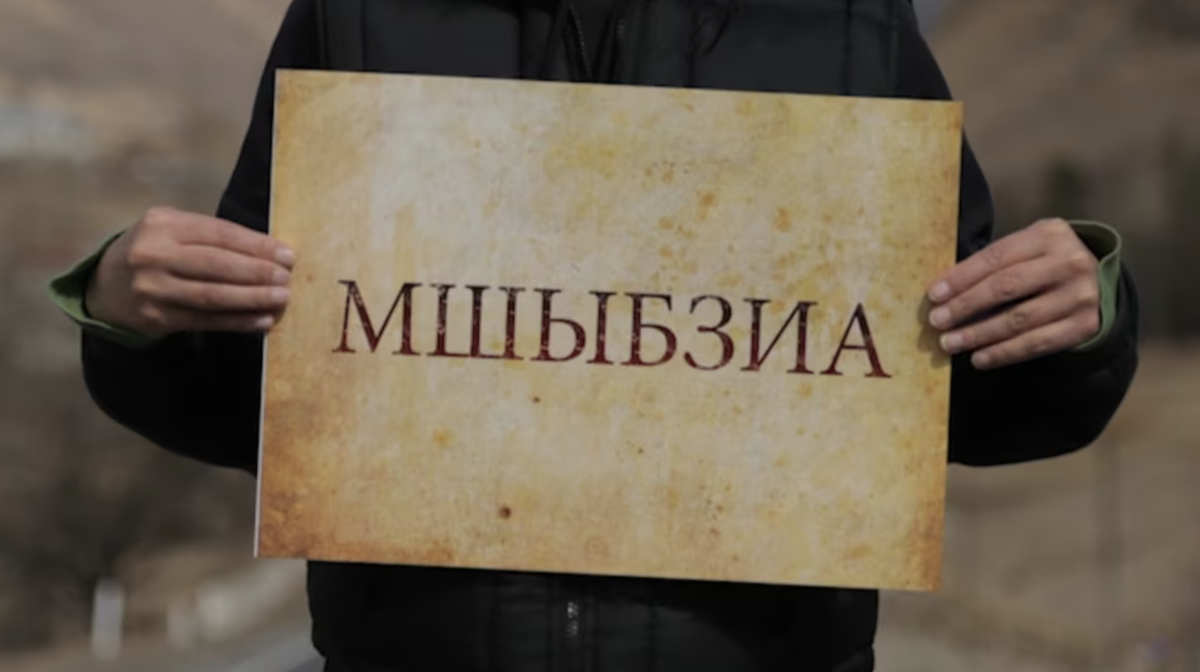

30 years after war in Abkhazia

“Thirty years It has become an unwritten tradition when Abkhazians and Georgians in social networks turn the next anniversary of the beginning and end of the Georgian-Abkhazian war into an occasion for heated discussions of the conflict. Thirty years have passed, but the degree of mutual hatred is still the same, as if the war ended only yesterday.

By the way, just yesterday I watched a short video shot in one of the Tbilisi cinemas, where a new film by Georgian director Nana Janelidze, “Go, Lisa”, dedicated to the Georgian-Abkhazian war, was being shown.

I do not speak Georgian, but I understood the general sense of what was happening. The film’s treatment of the Georgian-Abkhazian war clearly did not fit into the official picture, and a group of the Georgian public, outraged by this, organized a scandal. Next time, any Georgian director making a movie about the Georgian-Abkhazian war will think a hundred times whether it is worth deviating even a little from the orthodox position.

The current dispute is undoubtedly fueled by the global and regional context. Russia, bogged down in war with Ukraine, and the white flag over Nagorno-Karabakh, have clearly added fuel to this heated debate.

For many Georgians, this has stirred up the illusion that Abkhazia will finally return “to the bosom of Georgia”.

- Georgian-Abkhaz war, 1992-1993.How it was, a view from Tbilisi and Sukhum/i

- When the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict was closest to resolution – panel discussion & video

- Thirty years later: the Lata tragedy

“Now Russia will lose the war to Ukraine, then it will fall apart into small parts and Abkhazia will come to us without a fight. Karabakh surrendered so quickly, although there are several million Armenians, and these Abkhazians are so few that they can fit in one stadium. It would be good if they surrendered themselves, but if they do not understand, we will take them quickly through war” – this is a short paraphrase of Georgian “analysts” from social networks.

Politicians prefer not to talk about it out loud, but apparently this silence is temporary, as revanchist sentiments in Georgian society are only growing stronger. Before the war in Ukraine and the recent events in Nagorno-Karabakh they were much less, but now under the pressure of external circumstances they are growing likeyeast.

It is known how Georgia’s attempt to solve the “Abkhazian problem” militarily ended – with defeat in the war.

But now Georgians interpret those events as a Georgian-Russian war: they say that it was Russians who won and Abkhazians were timidly walking somewhere behind.

Indeed, we were not alone in that war. Volunteers from the North Caucasus and different regions of Russia came to our aid. There were not as many of them as it seems now, but they were volunteers. The Kremlin, where Boris Yeltsin, a friend of Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze, was then president, did not recruit them for this war.

But even if there were volunteers, the main burden was borne by Abkhazians themselves.

However, the mess that was observed in Russia was used by both Abkhazians and Georgians. At least, weapons of the warring parties were exclusively Soviet. But, unlike Tbilisi, to which Moscow gave the lion’s share of these weapons for nothing, Abkhazians had to buy every machine gun and every cartridge at their own expense.

Victory in this war cost the Abkhazians a catastrophic sacrifice — the loss of four percent of the ethnic group, a completely destroyed economy and all-round pressure from outside, including from Russia.

It was Moscow at the request of Tbilisi that immediately after the end of the war a whole set of political and economic sanctions was imposed on Abkhazia.

For example, Abkhazian men from 18 to 60 years of age were officially banned from entering the territory of Russia through the only checkpoint on the Russian-Abkhazian border on the river Psou. And for those who did not fall into this category, particularly women, crossing the border became a huge ordeal. For example, at one period on the Russian side of the border there was a wagon where everyone arriving from Abkhazia was obliged to take an AIDS test.

In addition, the passage of any transport and, accordingly, the movement of goods across the border was prohibited.

In general, at the mercy of Tbilisi, Russia turned Abkhazia into a ghetto until the early 2000s.

And the current refinement of the thesis that there was no Georgian-Abkhazian war, but there was a war between Russia and Georgia — this is talking into a hopeless void if we mean the settlement of the really existing Georgian-Abkhazian conflict. And this emptiness leads to a new war in which neither Georgians nor Abkhazians will win.

But, to be fair, it should be said that in our country, as well as in Georgian society, people are very cool towards direct negotiations between Tbilisi and Sukhum to resolve the conflict.

“We won the war, and what to talk to them about now. Let them recognize our statehood first, and then we will talk” – this is the dominant logic in public sentiment.

But the Georgian-Abkhazian war is an integral part of the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict. Without the conflict there would have been no war of 1992-93. And now the conflict exists, and its unresolved nature for the entire period of time preserves the threat of a new war, and under the current geopolitical arrangements makes it quite real.

But do we, Abkhazians and Georgians, need a new war?

Toponyms and terminology used by the author, as well as views, opinions and strategies expressed by them are theirs alone and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of JAMnews or any employees thereof. JAMnews reserves the right to delete comments it considers to be offensive, inflammatory, threatening or otherwise unacceptable