Why freedom of speech remains questionable in post-revolutionary Armenia

How does Armenia restrict freedom of speech and silences its media?

The Armenian National Assembly of the 7th convocation, the day before the end of its session, held its last extraordinary meeting – with the sole purpose of criminalizing insults. As a result, a new article appeared in the country’s Criminal Code – article 137.1 entitled “gross insult”. Unfortunately, this is not the only legislative initiative aimed at restricting freedom of speech in Armenia.

Lately, many similar manifestations have been observed in Armenia. The political force that carried out the revolution and came to power three years ago issues numerous restrictions on freedom of speech.

Chronicle of steps to restrict freedom of speech in Armenia, “evolution of punishments” for insults, restriction of freedom of speech assessed by local journalistic organizations and the international community, and details of the most recent legislative initiative.

- Armenian media under attack or undergoing long-needed reforms?

- Brawls and injured MP: Armenian parliament discusses government program

- Armenian government accused of political persecution as another opposition MP faces arrest

Silencing them by hitting their pockets

“Gross insult”, that is, swearing, insulting a person in other ways, according to the new article, is punishable by a fine in the amount of 100,000 to 1 million drams ($205-2050).

If the swearing is public, published on the Internet, or associated with the public activities of a person, then the fine will range from half a million to a million drams ($ 1025-2050).

By public activity, the authors of the law mean journalism, performing official duties, public service, and public or political activity. The punishment will be tougher if the insult is addressed to the “elite”, that is, a politician, journalist, public figure, or civil servant.

If the insult to the same person is repeated, the punishment involves not only a fine ranging from 1-3 million drams ($ 2050-6150) but also imprisonment from one to three months.

The ECtHR’s assessment

According to the case law of the European Court of Human Rights,

“The acceptable scope of criticism against the government is much wider than against a citizen or even a politician. In a democratic system, the work or mistakes of the government must be subject to detailed scrutiny not only by the legislature and the judiciary but also by the whole of society.

Moreover, the dominant position held by the government forces it to exercise restraint in the application of criminal or administrative penalties, in particular when there are other means to respond to unfounded publications or criticism”.

“Achievements in the field of democracy are under threat”

Human rights organization Freedom House issued a statement on August 4, noting the following:

“The adoption of a law criminalizing the grave insult of a public person means that Armenia’s achievements in the field of democracy and law are under threat. [․․․] Legislative criminalization of “grave insult” and other types of criticism, especially against government officials, stifles freedom of speech and political opposition. Therefore, we urge the Armenian authorities to abolish anti-constitutional laws that violate human rights”.

“Repressive and anti-constitutional initiatives”

A number of journalistic organizations in Armenia have also reacted to the recent events:

“This change is extremely dangerous, given the tendency of government officials, politicians, and other public figures to perceive even objective criticism as an insult and slander and take it court. And in the face of many problems associated with the judicial system, decisions on such claims can have fatal consequences for the future activities of the media.

Ignoring the criticism and appeals of the journalistic and expert community, the legislature approved a repressive initiative against the media which is not substantiated by deep professional research and analysis and pursues narrow political interests”.

The “evolution of punishment” for insults

Until 2010, insults and slander were criminalized in Armenia and for many years international structures have been repeating the need to decriminalize it and, eventually, this became a major achievement for the media and freedom of speech.

Since then, many civil claims have been filed with the courts, mainly against journalists and media outlets. During this period, the plaintiffs were inclined to demand large compensation, some of which were initially satisfied by the courts.

However, after a short time, the Constitutional and Cassation Court adopted a number of precedent decisions, in which important comments and definitions were given regarding the content and application of legal norms when considering claims for insult and defamation.

They were adopted as mandatory regulations, and they began to be consistently applied in courts. As a result, there were much fewer claims against media and journalists, and the maximum amount of compensation for insult or defamation was not applied – with rare exceptions.

A study of more than two dozen cases showed that the maximum fine revoked was 800,000 drams ($ 1,640 at the current exchange rate). The courts preferred to impose punishments in the form of a public refutation, publication of the court’s decision in the press, or their combination with symbolic monetary compensation.

Chronicle of restrictions on freedom of speech

The Velvet Revolution that took place in Armenia in 2018 inspired hope in the international community and local circle of experts that serious changes for the better would also take place in terms of freedom of speech, especially given the influence of the media on revolutionary processes. However, over the next three years, these expectations were not met.

Recently, the Armenian authorities have initiated a number of legislative changes, which have been sharply criticized in professional circles.

One of the most striking examples is the adoption of a new law regulating the broadcasting of audiovisual material. The tenders held under this law for the granting of licenses to television companies for broadcasting in a public multiplex led to the closure of a number of TV channels.

Another controversial initiative of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s team was the amendments and additions to the law “on mass media” which prohibited the publications of links to anonymous sources. For example, a domain registered on the network, a hosted website, an Internet website, an account in an app or a channel, the identity of the administrator of which is hidden from the reader.

The head of Yerevan Press Club Boris Navasardyan says that the proposed change cannot help counter misinformation, and the outlet can be held legally liable even for the correct information if it was obtained from an anonymous source:

“The absurdity is that the emphasis is not on the content but on the source of information, while the sources of information are protected by law. That is if the information does not correspond to reality, but the journalist does not want to indicate the source, he himself is responsible for it. And if the information is true, then it simply cannot have legal consequences”.

A few months ago, journalists were seriously concerned about the legislative initiative proposed by the former deputy speaker of the parliament, Alen Simonyan, to triple the fine for insult and libel and increase it up to 3-6 million drams ($ 6150 -12,300).

This bill was passed on March 24, 2021. As a justification, the Armenian authorities cited the laws of a number of countries as an example:

“In Belgium, Norway, and Italy, a fine of up to 2,000 euros has been established for insult and defamation. In the UK, defamation of a candidate during an election, if proven guilty in court, can be punishable with a fine of up to £5,000.

In France, insult and defamation can lead to both administrative and criminal liability. For publicly insulting a person on racial, religious, ethnic, gender or any other grounds, a punishment of imprisonment for a period of 6 months to 1 year or a fine of 22,500 to 45,000 euros may be imposed”.

It must, however, be noted that the authors of the law did not hide the fact that the indicated amounts of fines were practically not applied in these countries, and the punishments were only symbolic – for example, a fine of 1 euro.

Alain Simonyan was also the author of the latest initiative aimed at restricting freedom of speech. By his decision, the security rules in the building of the National Assembly were changed, which, in fact, limited the right of movement of journalists.

From now on, journalists accredited in parliament can only work in specially designated areas of the building.

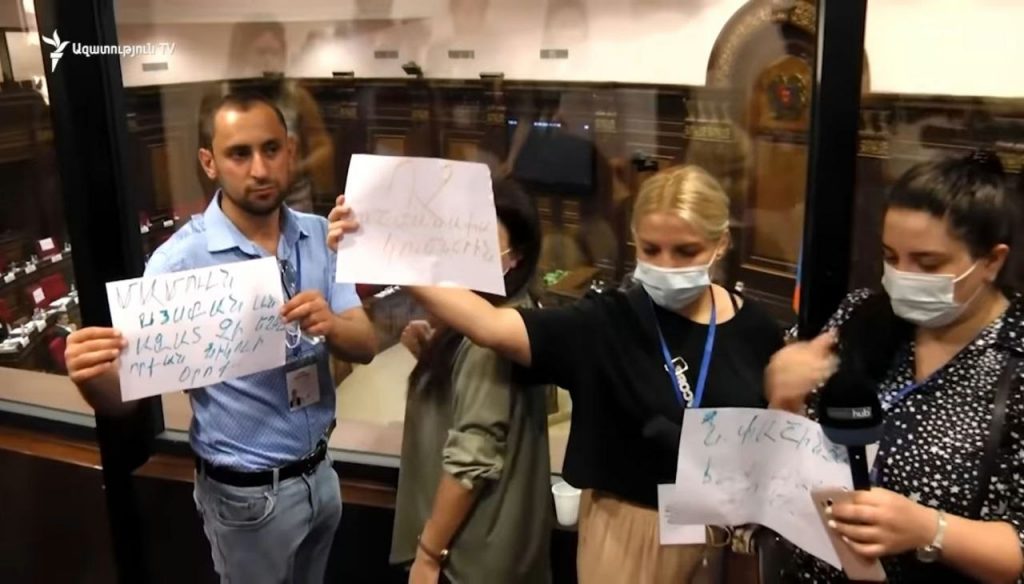

Journalistic organizations again issued a joint statement condemning this decision, which the authorities ignored, like the previous ones. The rally of journalists accredited in parliament aimed at drawing the attention of the prime minister was held in a box set aside for their work where they held in their hands posters with the words “Nikol Pashinyan, you are no longer a journalist”, “The press has never been more unfree than in Nikol’s time”.

Dynamics of recent years

According to the report of the Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression, the number of harassment against freedom of speech in 2020 in Armenia reached 177, up from 134 last year. There were also 6 cases of physical violence against journalists with 11 victims. An intensive flow of lawsuits against the media remained, their number reached 72. By the way, in 2019 more lawsuits were filed against the media than in 2018 and 2017 combined.

In the Freedom House report entitled “Freedom on the Internet 2020” Armenia was included in the list of “free” countries, while in the report “Freedom in the world 2021” the country was listed as “partially free”. And in the report “Countries in Transition 2021” Armenia has already been included in the list of “half-formed authoritarian regimes”.