Water flows, responsibility vanishes: difference between Baku and Vilnius

Water supply issues in Azerbaijan

This article is based on data and analysis published by Toghrul Mashalli on his public Telegram channel.

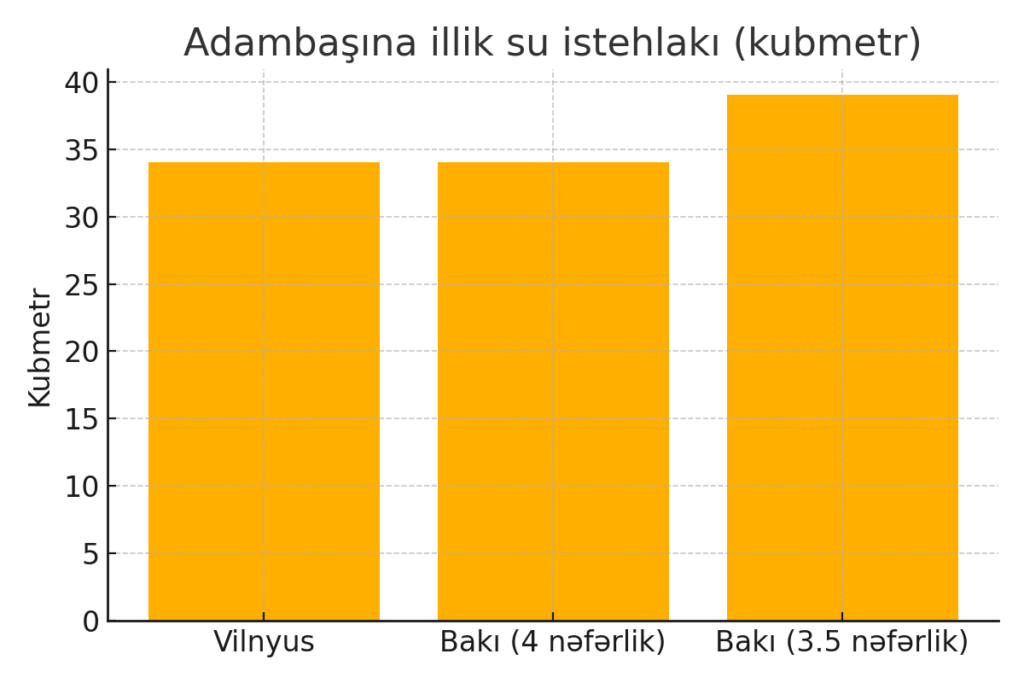

In Lithuania’s capital, Vilnius, the water supply sector stands out for its transparency. According to a report by Vilniaus Vandenys, the company responsible for the city’s water services, Vilnius residents consumed 36 million cubic metres of water in 2024. Of that, half — 18 million cubic metres — went directly to household use. This amounts to 34 cubic metres of water per person annually.

As economist and researcher Toghrul Mashalli noted, a similar level of consumption is observed in Azerbaijan.

Baku also reports 34 cubic metres of water per person per year

According to 2023 data, a total of 165 million cubic metres of water was consumed in Baku, Sumgayit, and the Absheron district of Azerbaijan. This volume was distributed among 1.22 million subscribers.

Assuming an average household size of four people per subscriber, this also amounts to around 34 cubic metres of water per person per year — the same as in Vilnius.

If a more realistic average household size of 3.5 people is used, per capita consumption rises to about 39 cubic metres. According to Mashalli, this difference is due to climate and lifestyle factors and is perfectly normal.

But the main problem lies not in consumption, but in management

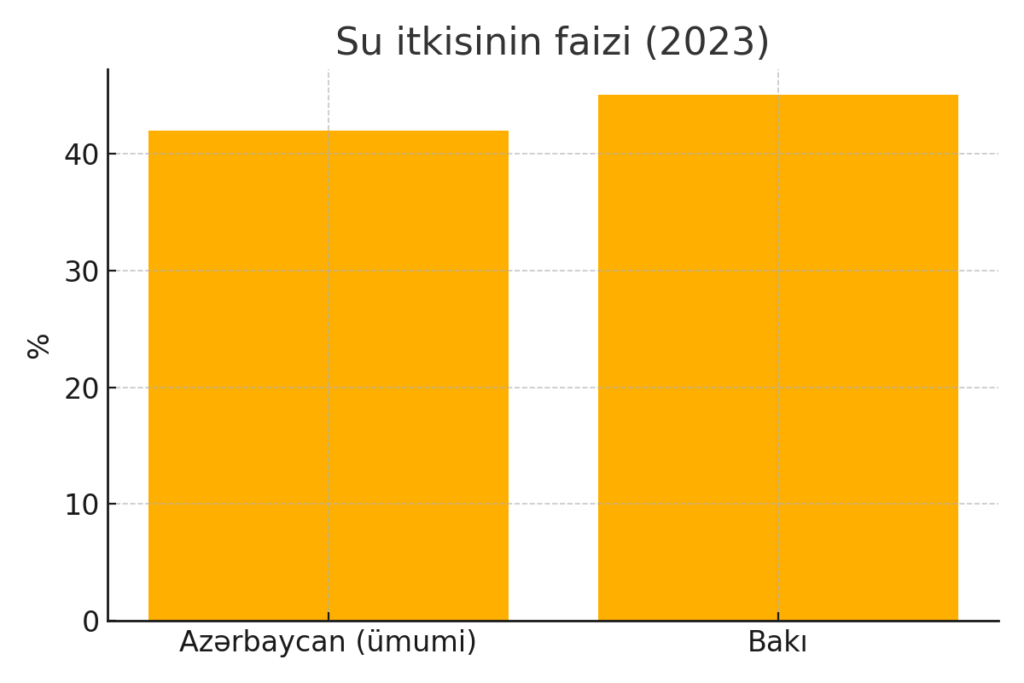

The key issue highlighted by Toghrul Mashalli is the water loss rate hidden behind the consumption figures. According to official statistics, in 2023, 42% of all water supplied to consumers in Azerbaijan was either unaccounted for or lost due to technical reasons. In Baku, this figure is even higher — 45%.

This means that out of every 100 cubic metres of water, only around 55 actually reaches the end user, while the rest “disappears” within the system. Water losses are attributed to both technical faults and gaps in the accounting system.

Raise tariffs or reform management?

Raising water tariffs is often suggested as a solution. However, as Mashalli points out, this approach only increases the financial burden on the population. Meanwhile, the main investments in water infrastructure are already covered by the state budget. The key issue is how these funds are spent.

In other words, instead of higher tariffs, greater transparency and accountability mechanisms offer a more effective path to reducing losses.

In search of invisible water

Water supply is not just a technical issue — it also reflects governance, public policy, and social responsibility. In terms of per capita water consumption, Lithuania and Azerbaijan may appear similar. But as Mashalli’s analysis shows, the real difference lies not in the numbers, but in the approach.

And like the invisible water that’s lost each day, this difference results in significant losses.