Treatment in a Yerevan salt mine: clinic loses state support but may attract tourists

Treatment in a Yerevan salt mine

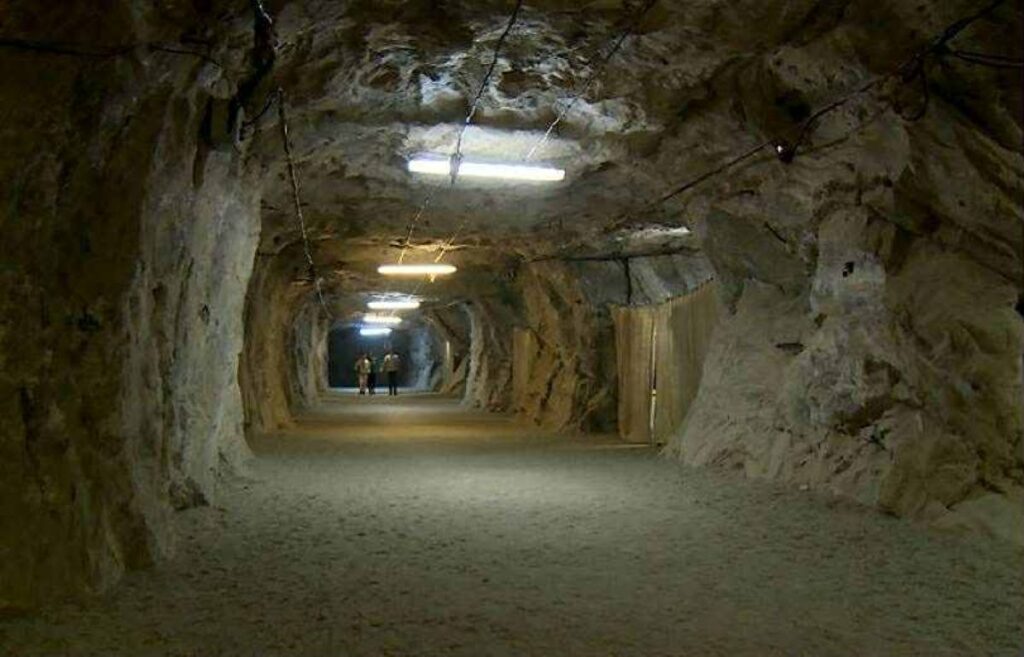

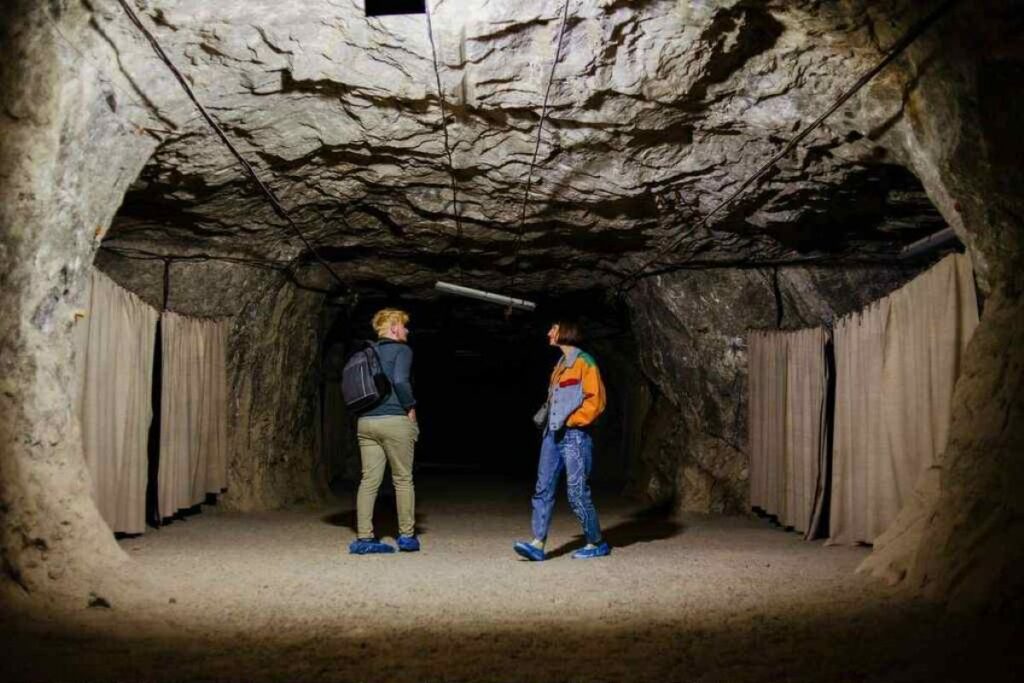

In Yerevan, 235 metres underground, lies the Republican Centre of Speleotherapy, established in 1987. The centre was allocated 4,000 square metres inside the Avan salt mine. People come here to treat asthma, bronchitis, allergies and other respiratory conditions. Inside the mine, there are rest areas, sleeping rooms, walking paths and spaces for exercise.

We look at the challenges the speleotherapy centre has faced since losing state support, and what prospects it has to survive and continue its work.

- Armenia gradually approaching compulsory medical insurance

- Obstetric violence in Armenia: No data, no complaints – no problem?

- Armenian diaspora doctors propose changes to healthcare system in Armenia

- ‘Blacklist’ of Armenian doctors: medical errors and possible consequences

Treatment requires 20 days without breaks, five hours each day

The salt cave has a unique microclimate. Air composition, humidity and temperature remain constant, unaffected by the weather or outside factors. The temperature stays at 20C all year round. There are no magnetic or radioactive waves here, no dust. According to the centre’s doctors, “patients breathe air enriched only with sodium chloride ions.” They say the air is close to sea air, which strengthens the immune system and helps treat or ease illnesses.

“Patients stay here for five hours a day. The course lasts 20 days and must be completed without interruption to be effective. Speleotherapy works especially well for children, who often fall ill and suffer from a lingering cough. Thanks to the salty air, their immunity is strengthened. If you look at the walls and floor, you can see even with the naked eye that it’s not pure salt, there are impurities. The salt also contains various trace elements, which enrich the air and have a therapeutic effect on patients,” says the centre’s head doctor, Anush Voskanyan.

She stresses that speleotherapy does not replace medicine. For conditions such as asthma, prescribed drugs cannot be abandoned, and patients continue taking them during therapy.

“After the course, however, the number of pills is often reduced depending on the patient’s progress. And many children aged seven to eight show full recovery, which is rare with these diseases. Patients spend time walking, doing gymnastics, breathing exercises; young people play tennis or billiards. We’ve tried to create conditions so that people don’t get bored,” Voskanyan adds.

Treatment at the centre became paid after losing state support

The Ministry of Health stopped funding the centre in 2020. Since then, it has no longer offered free treatment under the state healthcare programme, as it once did.

Acting director Gurgen Akopyan says he has appealed several times to reverse the decision but has repeatedly been told the same thing: the centre provides alternative treatment, not evidence-based medicine, which is what the state finances.

In Armenia and abroad, speleotherapy is considered part of a comprehensive approach to disease prevention and treatment — a form of rehabilitation. It is usually offered in multidisciplinary medical institutions as part of a patient’s treatment. But state orders do not cover such single-profile clinics.

Akopyan argues that this is the only speleotherapy centre in the region and that people should not be deprived of the chance to improve their health:

“This is a national treasure. But right now, we are effectively bankrupt. We once had 16 employees. After cuts, four now work on civil contracts and only two remain on staff. Unsurprisingly, patient numbers have also fallen. The centre used to treat around 300 people a year. State support amounted to 28 million drams ($73,490) annually, while commercial income from paying patients was about 4 million drams ($10,490).

That was enough to cover all our expenses and pay staff salaries. Now, with no state support, our only income comes from patients’ fees. But this barely covers wages for six employees and the cost of running the lift.”

According to him, “asthma is a disease of the poor,” caused by harsh living conditions — when people cannot heat their homes, lack warm clothes or do not eat properly.

He explains that such patients cannot afford to pay 10,000 drams ($26) for each visit. As an alternative, doctors suggest they buy salt lamps made by the centre for the same price. The lamps are placed in bedrooms to create an atmosphere similar to that of the salt mine.

The speleotherapy centre can only be reached by the salt mine’s lift, which also transports chunks of salt extracted from underground. Each month, the centre pays the mine for its patients’ use of the lift. But in months when too few patients come, it struggles to cover the fee and falls into debt.

Akopyan says the lift needs at least five patients a day to cover the cost. Yet even when there are only two or three, they still run it.

What’s more, since the centre was founded the beds for patients have never been replaced. Nor have the billiard and table tennis tables, which keep patients entertained during the five-hour treatment sessions.

Little chance of being recognised as evidence-based medicine

Pulmonologist Viktoria Ghazaryan says that over the years she has repeatedly seen speleotherapy’s effectiveness. But to have it recognised as evidence-based medicine, large-scale studies would be needed — and none are being carried out. She adds that there are also methodological problems: there is no clear data on who was treated, their condition before and after, or what medication they were taking alongside the therapy.

“It is very difficult to measure the effect. A patient’s condition may not improve immediately after the course. The result may only become clear months later, when they notice they no longer fall ill or that their illness has eased. Some patients also continue to take medication, which makes it hard to say whether the improvement comes from the drugs or the therapy. That’s why speleotherapy is considered an alternative, supplementary method. It is highly valued in eastern medicine. If it had no positive effect, it would not be so popular there,” she says.

According to the pulmonologist, many speleotherapy treatment rooms have now opened in Yerevan. Some of them attempt to artificially recreate the natural climate of the cave. Ghazaryan believes that even these artificial rooms have a positive impact on patients.

Armenia has potential to develop medical tourism

Tourism specialist Sona Agbalyan believes the region’s only speleotherapy centre could become one of Armenia’s calling cards in medical tourism. But in this field, the country lags behind its neighbours, Turkiye and Georgia.

“Turkiye is now considered the regional leader in medical tourism. Years ago, people travelled to Israel or Germany for treatment, but now they go to Turkiye. In recent years Georgia has also taken very aggressive — and very successful — steps in this niche. Unfortunately, we are falling behind, even though the country clearly has potential. Medical tourism has several directions, one of them being specialised clinics — dentistry, cosmetology, plastic surgery. Our clinics lose out because they are more expensive than in Turkiye and Georgia. Another possible direction is sanatoriums, but that is also not being promoted,” Agbalyan says.

According to her, Armenian sanatoriums are little known abroad and are in demand only inside the country:

“There is a gap in the tourism strategy. We promote Armenia, particularly Yerevan, as a tourist destination. But individual towns are not promoted as destinations in their own right. For example, Jermuk as a spa town or Tsaghkadzor as a sports town are not marketed. We don’t advertise the fact that asthma can be treated in a natural salt cave in Armenia. Yet this could be a very effective move. To explain my point, I’ll use the example of Dubai chocolate. It was marketed so well that people now travel to Dubai not for the sights but to try Dubai chocolate. In the same way, people could come to Armenia for the salt cave, for helicopter rides and many other local experiences.”

Agbalyan says such targeted advertising should be included in the new strategy being developed by the Tourism Committee.

Yerevan salt mine