Op-ed: ‘Good Neighbour’ biennial in Turkey focuses on raising questions and searching for answers

‘A Good Neighbour’ was the theme chosen for this year’s annual Biennale of Contemporary Art in Istanbul. The topic appeared to be rather unexpected. The Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts has been organizing the Istanbul Biennial every autumn since 1987 and each time it becomes a meeting point between artists from diverse cultures and their audiences.

This time the biennale’s organizers decided to challenge the audience asking truly many questions, first in the form of a questionnaire. Thereafter they distributed the questions along with their answers throughout the city via posters and short video clips.

The question “What does it mean to be a good neighbour?” and over 40 others were asked. In some way the organizers ended up conducting a sort of test.

The Istanbul Biennial offered a number of answers to the questions that were asked, many of which were humorous and mentioned in an everyday context. Some example answers of a good neighbor were:

- someone who is your friend on Facebook;

- someone who doesn’t have pets;

- someone who reads the same newspaper you like to read;

- someone who lets you use his wi-fi without a password;

- someone who cooks you something to eat when you’re sick;

- someone who will collect your mail when you’re away.

One of the answers, ‘someone you are not afraid of’, can be considered the most relevant and symbolic one. Fear has become commonplace because there is too much instability in our lives.

Fear of loss, or of the idea that you might not be accepted or understood was a common theme at the Biennial. Although it wasn’t said out loud it was hinted at and was included in a book of memoirs called ‘Histories’ which was specially written for the Biennial. It also featured in the individual works presented.

The Istanbul Biennial took place for the 15th time, but this time there was tension in the air. With Turkey’s coup attempt, the war on the country’s borders, the flow of millions of refugees from Syria, terror attacks (in Istanbul alone there have been 12 in 2017) and more censorship, art has become more challenging. Many artists were at a loss, unable to decide whether it was worth participating in the Biennial or not.

“Last year we had so many problems that we even started to question whether the biennale should take place at all,” says Elif Kamishli, the coordinator of the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts.

In earlier years, the Biennial presented itself as a platform for the brave, for those unafraid of political questions in art. In 2013 for example, it had the topic ‘Mom, am I a barbarian?’ which many associated with civil resistance.

In 2016, the Biennial decided focused on the ‘inner life’ of a person, life in a comfortable environment without unwanted surprises.

Scandinavian artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, who are known as the creative duo ‘Elmgreen and Dragset’ were chosen to supervise the Biennial. They decided to show important problems from the perspective of a a family home as a small world in its own right. In their opinion, a warm and cozy home with its smells and memories of childhood can become a lifebuoy amidst political problems and catastrophes.

Elmgreen and Dragset, who are not only colleagues but also a couple, are sure that the ‘network of relationships is revealed like the rings of an invisible chain spreading rapidly from private to public and from there to all of life’.

Political views have to give place to people’s emotions. It is like an escape into the internal world. A person must ‘take shelter’ in order to remain a human being.

Iranian artist Mirak Jamal, whose family left their homeland after the Islamic Revolution moved about constantly during his childhood from one country to another. The memory of a destroyed and unfinished home was always with him.

The Istanbul Modern Museum exhibition has, at first sight, seemingly naive and childish sketches, which portray an unhappy child who had lived through war and losses.

Moroccan artist Latifa Echakhch presented her frescoe-installation ‘Crowd Fade’, in which demonstrators of the Istanbul Gezi park who protested in 2013 stare at each other from opposing walls.

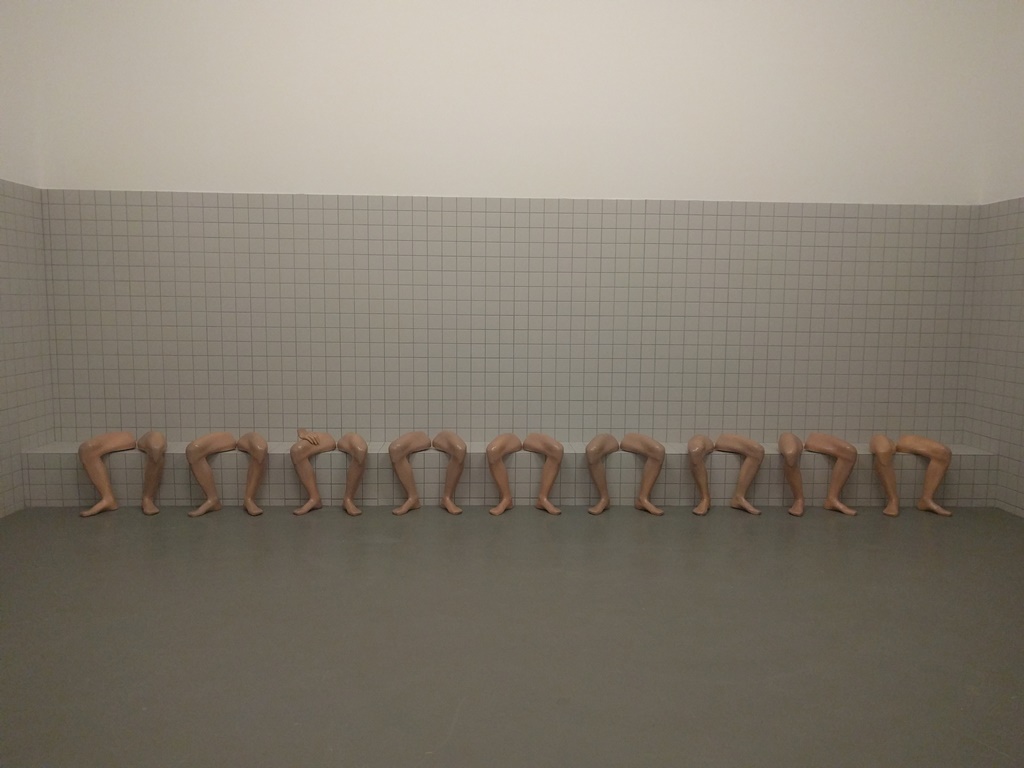

The Turkish artist Candeger Furtun created ‘Nine Pairs of Ceramic Legs in a Hamam’wherein he, like in a Turkish bath, arranged human limbs as a reminder that all people are the same, equal and naked.

There was an exhibition in a real hamam (Turkish bath). On the northen side of Istanbul in the Küçük Mustafa Pasha hamam, Tugce Tuna presented a dance performance called ‘Body Drops’ with the theme being rituals and traditions.

In the small but very interesting workshop in the Asmalimescit neighborhood, there was one installation which portrayed a home: a dining room, dishes and the sounds of familial life. A short video-presentation was featured, which started from absolute darkness. Then some parts of the image were slowly illuminated, and then lost in the darkness again.

Austrian Leander Schonweger in his installation ‘Our Family Lost’ portrayed rooms which continued without end into one another and were constantly becoming smaller. In the end, they turned into a prison room.

Real neighbors

The Istanbul Biennial had chosen the theme of neighbors – but ignored Armenians and Greeks who featured prominently in the history of Turkey. There were no works by Armenian and Greek artists in the exhibition, which was surprising given the fact that these countries border Turkey. This could become a great opportunity for dialogue.

The coordinator of the exhibition, Elif Kamishli, agrees that it was a good opportunity but says that the decision was not taken from a political point of view but from an artistic one:

“Yes, we don’t have any artists representing Armenia. But our curators were considering artistic value. The exhibition is called ‘Good Neighbor’ – but this doesn’t mean that artists from all neighboring countries – Greece, Bulgaria, Armenia – had to be invited.”

The creators of the Istanbul Biennial tried to be optimistic, bringing to the front not the relationship between an individual and the world, but the personal relationships of people. But with one condition: these people do not conflict, but communicate.

“Art is not a kind of mirror which reflects in an obvious way the surrounding reality. Our curators try to deal with language which is not connected to hot political discussions because it is harmful to art,” comments Elif Kamishli on the conception of the Biennial.

‘Good Neighbour’, which went on for three months was visited by half a million people.

This is an important indicator for Turkey. The Biennial had become a tourist attraction and helped Turkey to compete on the international map of art.