“Time stopped for us”

Karabakh war

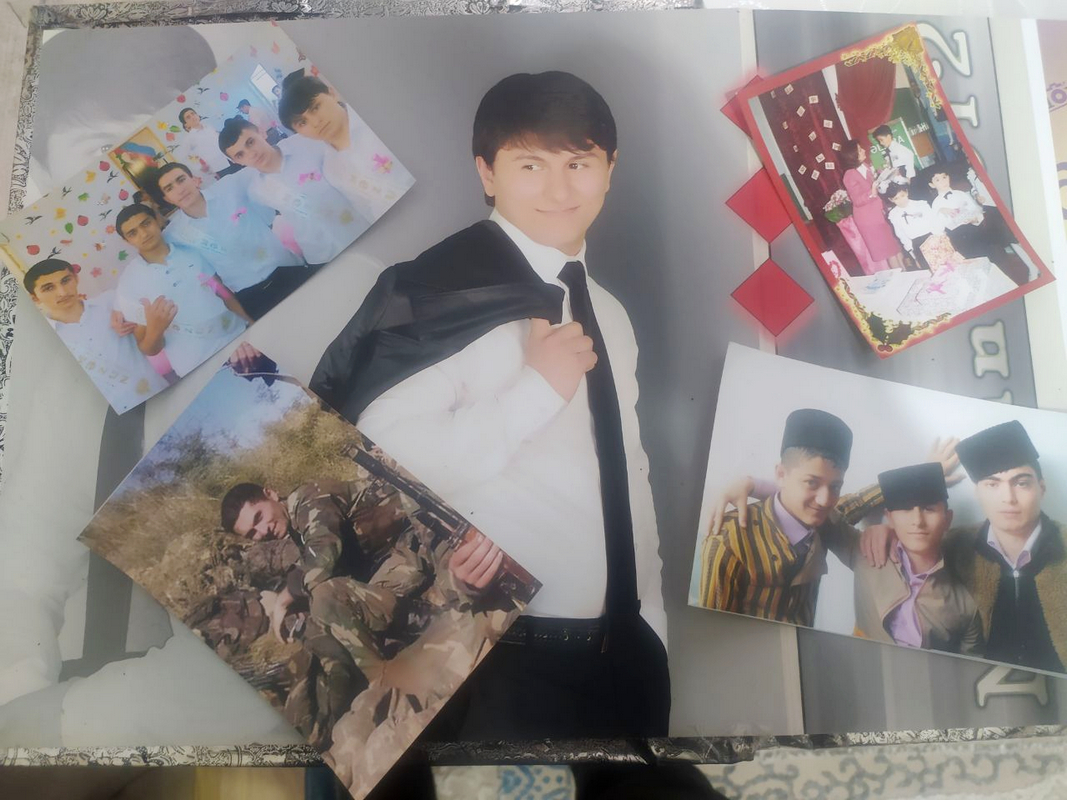

Dilber Ahadzade sent her two sons to the second Karabakh war in 2020. One of them did not return. Having moved to Baku from the country and not having her own housing, for many years Dilber lived in an abandoned dormitory —- two rooms in substandard condition, and there she raised her sons. After the death of her eldest, the state allocated her a bright, new, two-room apartment. Every corner of this apartment, from the very doorway, she decorated with photographs and other reminders of Elsever. Her only consolation now is her son Farid, who was wounded in the war and her husband, who suffered a stroke long before the war, and whom she hopes will one day recover.

Zabrat is located 30 kilometers from Baku. Many houses here were built for families internally displaced as a result of the first Karabakh war. But now those internal refugees must return to Karabakh, so the process of settling has stopped, and apartments have been distributed as compensation to the families of deceased and veterans of the second Karabakh war.

Along the street are photos of the fallen — smiling young men in army uniforms. The courtyards of the apartment buildings that make up this peculiar burg, built as if purposely out of sight, are deserted and quiet.

“On the morning of September 21 the military commissariat called”, Dilber says. “Elsever was at work, they called his father. I took the phone. They told Elsever to report immediately to the Commissariat. That evening, Elsever waited a little for his brother to say goodbye to him. He loved him very much. But Farid was late from work, Elsever was already late, couldn’t wait any longer and left.”

Dilber sobs and immediately asks her younger son to come out.

She rubs palms together, wipes away tears, straightens up.

“I can’t cry in front of him. And he doesn’t cry with me. Two years have passed, but it seems to me that everything just happened yesterday. Elsever was taken away on the pretext of military training. Elsever spent a week in Baku, then he was sent to the front. Farid was taken away the same week, on the 29th. I saw Farid off myself.”

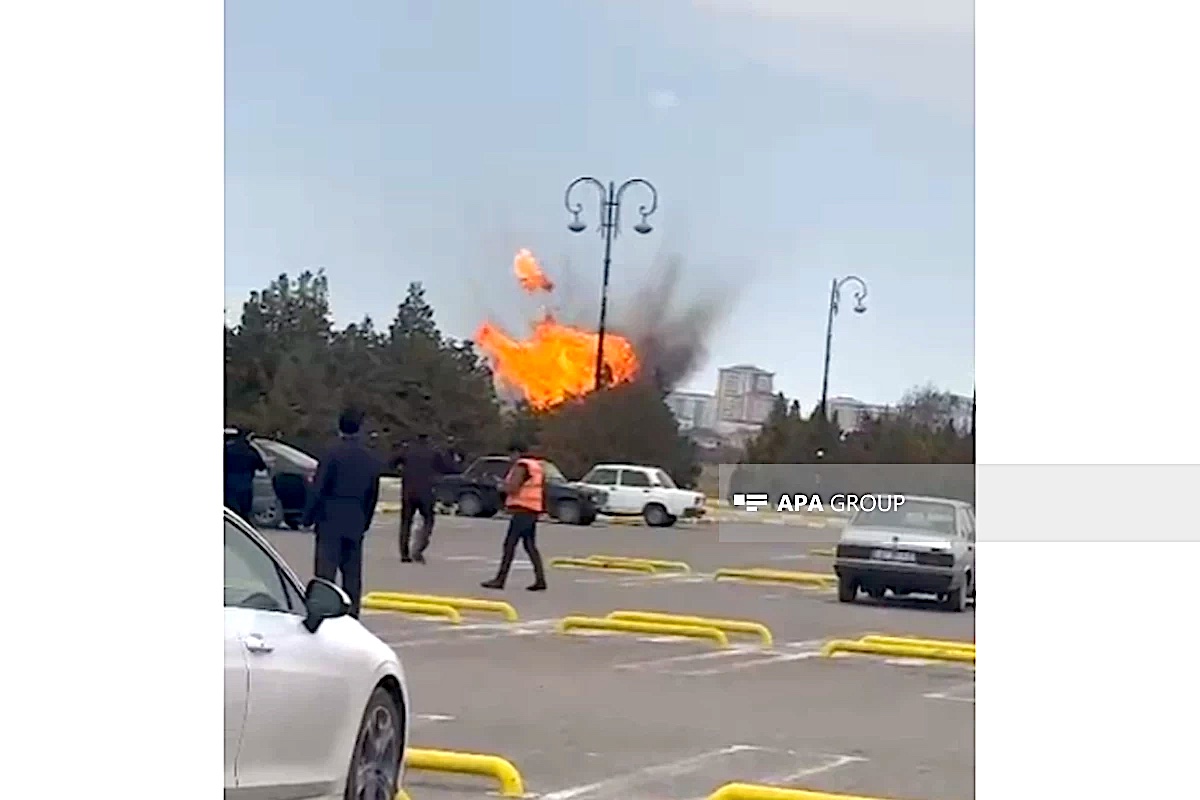

During the 44-day second Karabakh war, Azerbaijan regained control over part of Karabakh and seven adjacent regions. Both sides suffered numerous losses. Since then the two countries have not been able to make peace.

Dilber Ahadzade did not know that her son was on the front line until his death.

“I talked to Elsever every day, and on the day of his death, too, early in the morning.

“Pray for us, he said. He was worried about Farid. I wanted him to come back. On the 24th, Elsever was brought back from the front. People crowded in the corridor. The neighbors were told to notify me, but no one dared. Leaving the apartment, I experienced a strange feeling: everyone is looking at me, I ask questions, they don’t answer, it drove me crazy. Then someone said that Elsever was wounded. I replied that if he had been wounded, he would not have been brought here, but to the hospital.

When my husband heard weeping, we first told him that his son had been wounded. Then, when they began to decide where to bury him, he understood everything and broke down. And Farid found out after he returned from the war. That’s how we deceived each other. Today I went to the Alley of Martyrs, where Elsever is buried, all the mothers were there. We can’t get used to it.”

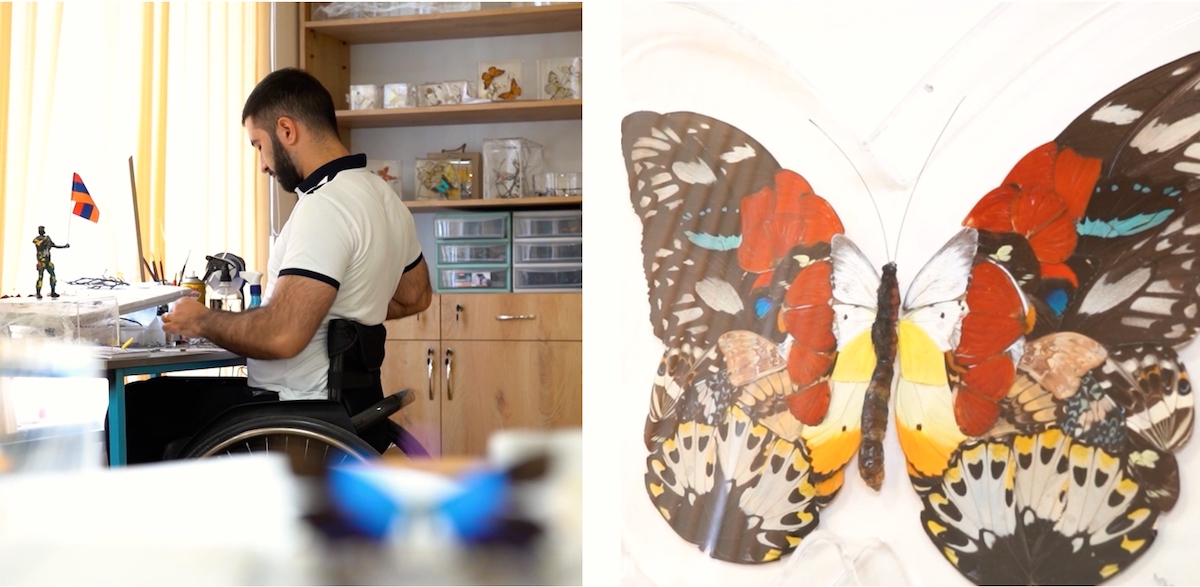

Dilber’s consolation was Farid. She thanks God that her son, although wounded, returned from the war alive. And remembering with what difficulty she raised her children in two rooms of a hostel, she feels a senselessness.

“Elsever cried a lot when he was little. And he was a naughty one. I was constantly complaining about it. He was an accident prone child. But smart. My sons and I were friends, I never intimidated them, never beat them. Neither me nor their father. So they told me everything, no matter what happened. It’s a pity that fate turned out that way. He worked hard and went to college. He grew into a reserved, honest person. He had few friends, but they were all the same as him.”

Clashes still occur periodically between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Dilber says that the news of someone’s death seems to pick the scab from her wound.

“When I hear that someone’s died at the front line, I am back to the day when they brought Elsever’s body. I still don’t understand how I could bear it and not go crazy. I am naturally calm, quiet, I can’t cry aloud. There are people who can express it, expel the pain from the heart with tears. But I keep everything to myself. I keep repeating that we are stuck in 2020. Nothing changes for us. Whatever I do, I keep recalling the time when Elsever was alive. How we went with him somewhere, what he said. And when we argue at home with Farid about something, he says that if Elsever were alive he would say this, would do that.

Dilber says that Farid took the loss of his brother very hard:

“Farid is having a very difficult time. To support us, he does not cry, he restrains himself. And when it comes to the war, he talks about it as if he had been to a resort. But I know that he, too, saw blood and buried his comrades. Recently, he and his friends gathered to celebrate his birthday. He and Elsever always arranged something for each other on birthdays. Evening came. I went into his room and saw that he was crying. It was the only time I saw him cry. I left him alone so that he could cry it out. It’s my turn to cry when he leaves for work. We go to the cemetery separately.”

Dilber thinks that the sacrifices were meaningless if the conflict continues:

“True, I drive these thoughts away from me. But my son was here beside me me, he didn’t touch anyone. I won’t lie, if there’s another war, I won’t send Farid to the front. Elsever already deserved paradise during his lifetime, he did not need to die young for this. And he left, leaving us all his dreams. We lived in a dormitory for so many years, he so wanted us to have our own housing, and now I live in his apartment.”

When our conversation is over, Dilber calls Farid into the room, pours tea. Farid says that he is preparing to enter the university, that the exams are difficult and a diploma is necessary to get a job.

Seeing me off, Dilber says that not many families of war dead and veterans live in this settlement. Many houses are for sale. It is quiet here even in the evenings. Although the courtyards are brightly lit, in the houses the light is on in only a few windows.