Blind musicians and their unique project in Armenia

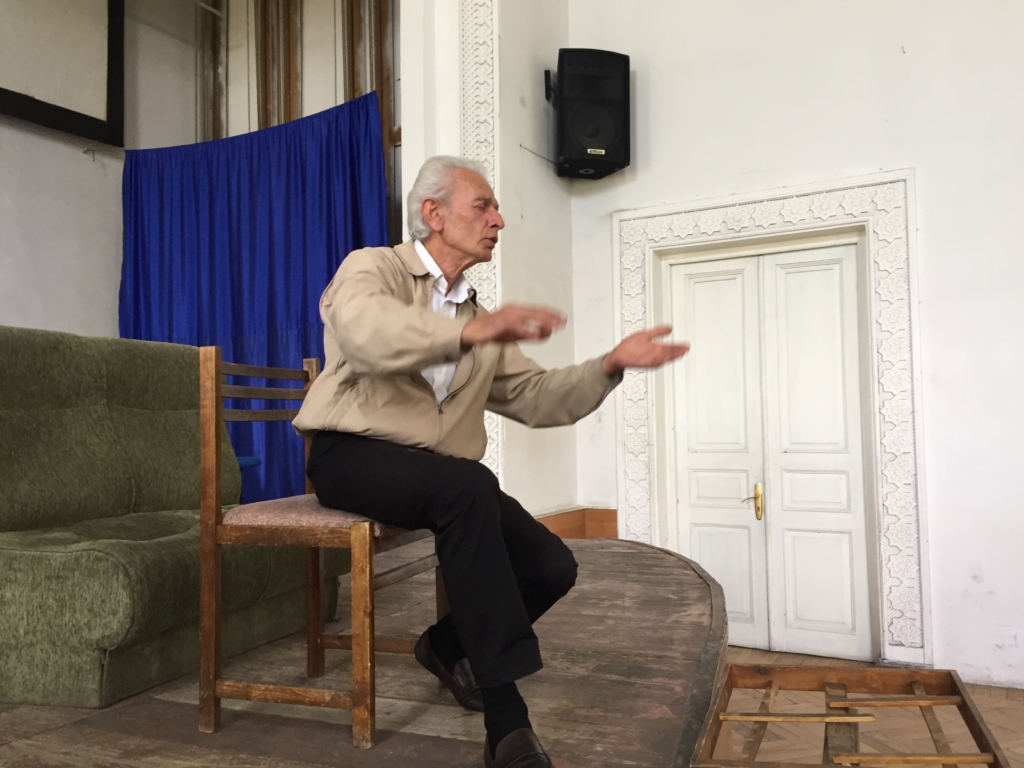

The silence in the hall breaks – the blind choir gathers for yet another rehearsal. They come in slowly, one by one in a business-like manner. They sing, eyes fixed on the conductor who is standing on the stage. They catch his every word and sigh. Somehow, grasping all the artistic movements of their conductor’s hands, the 40-year-old choir of the blind performs yet another musical piece.

“Throughout the years, in the process of communication, they’ve ‘brought me up’ and have accustomed themselves to my musical thinking. We have become one whole: one body, one soul, the same perception. Our choir has a very high level of performance. We constantly rehearse the pieces from our repertoire, and every time we discover something new in them,” says Karlen Aleksanyan, the Head of the Association of the Blind of Armenia.

In his words, the world’s first blind choir was founded in Bulgaria in the 1940s. Thereafter similar ensembles were established in Lithuania and Georgia, with Armenia being the fourth. Aleksanyan recalls that 40 years ago, when he was first offered to work with this newly set-up choir he was at a loss, thinking how he was supposed to direct it.

“It was not an amateur, but rather a paid professional group. In the first years we learned the musical pieces by ear. Then the program gradually became more complicated, and it was impossible to perform all that from memory. So, together with the blind performers, we switched to Braille music notation, thus providing them with musical education,” says Aleksanyan.

The choir’s best years ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The blind performers are facing hard times now. Susanna Buniatyan, an HR manager for the musical ensembles at the Association of the Blind of Armenia, recalled all the awards, titles and the countries that the ensemble toured in. As she pointed out, in Soviet times the ensemble was funded by the Blind Association. However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when all centers for the blind were closed, the choir stopped receiving funding.

“Our performers were paid RUB 220, whereas now they receive just AMD 15 000 (less than USD 30), and they get salaries only a few times a year. We’ve been living on donations for 20 years already. For seven years we were funded by the Jinishian Memorial Foundation, and then we received funding for one year from the Open Society Institute. For over a decade, I’ve been sending letters to the Ministry of Culture, requesting the choir to be granted state musical ensemble status. But all my efforts are in vain,” said Buniatyan.

The youngest performer in the choir is 22 years old, and the oldest one 80. Most of the performers are elderly. There are few young people among the choir members.

“They don’t see any prospects for themselves here. Their argument is as follows: Let’s say we sing in the choir 2 hours a day for our own enjoyment. What are we supposed to do after the rehearsal? Shall we go home and keep starving? That’s the problem. If we had stable funding, if we could offer people some additional income, young people would join the choir, and we would make efforts so that it could further exist,” said the choir conductor.

Meanwhile, the current composition of the choir faithfully keeps rehearsing twice a week, despite all the problems. Kamarnik Gevorgyan, one of the singers, is a lecturer at the Yerevan State University. In his words, he can’t imagine living without the choir where he has been performing since the first day it was founded.

“Once you get attached to a creative process and feel a touch of its beauty, then it’s hard to live without it. You want to soak up the art as it complements and enriches your life. Choral art is a delicate matter. You should have team work skills, you should be able to hear others and perform together. So we try to come here no matter what the situation is,” said Kamarnik Gevorgyan.

The choir’s repertoire is comprised of about 500 musical compositions, including folk melodies, classic works and operatic arias. The choir performs musical pieces by Bach, Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, Handel, Gounod, Komitas etc.

“We were the only ensemble that performed Bach’s ‘High Mass’ (Hoch Messe). It’s a very complex and voluminous piece. We also performed Georgi Sviridov’s ‘Pushkin’s Garland’. We did a monumental job. In Russia, this musical piece is performed jointly by two choirs,” said Karlen Aleksanyan.

The rehearsal lasts for nearly two hours. The choir is rehearsing a musical piece by Komitas. The melody is interrupted by the conductor’s voice, but then it softly flows over the entire hall again. Nelly Sargsyan is sitting in the first row, following the conductor with utmost attention.

“Although we come here with a sighted guide and spend double our money – despite the fact that we are short of it and nearly all of us are living in hard social conditions – we come here anyway, because we can’t live without singing. That’s our job and the only thing we wish is that our work be duly appreciated,” she said.

The blind musicians receive disability benefits that are hardly enough to solve even the most basic of problems. Nelly Sargsyan gets AMD 55 000 (USD 115), and she spends most of it on medicine.

“It should be taken into account that we are disabled people, and we are on the brink of old age. We should at least be paid salaries so that we can survive. We receive spiritual food, but we don’t get anything from a financial point of view – we are poverty-stricken,” she said.

The choir is made up of 27 people, including sighted ones. Ludmila Petrosyan, the ensemble soloist, is one of them. She says there should be some sighted singers in the choir, so that they could assist the blind performers.

“Getting here is a real problem for the blind. In the past there was a car serving the choir members, bringing all of them here together, and then driving them back home. But it’s not the case now. Each of them has to be accompanied by a family member. Those people come here, sit in the hall and wait until the rehearsal is over. It’s very difficult of course, but it gives a powerful energy charge. To feel music at least twice a week… Music is like a disease for a musician, a singer. It brings spiritual satisfaction,” says Ludmila Petrosyan.

Karlen Aleksanian praises his mentees:

“And there is one important aspect: eye contact actually distracts people, so in this case they concentrate really well. They remember everything I tell them right away. It’s a highly professional choir.”

The singers are nostalgic about the choir’s better days, when they traveled on tours, when their masterly performances were in demand. They still remember the thunder of applause that audiences lavished them with. Susanna Buniatyan showed a gold medal from the Culture Ministry, which the choir was awarded with this year, as well as albums with the choir’s biography. There are also letters addressed to various agencies which have been left unanswered.

“I even appealed to the president, requesting that the choir be granted state ensemble status, or be transferred under the jurisdiction of a certain agency so that we could submit an application and be provided funding for our concerts,” said Buniatyan.

Karlen Aleksanyan believes it’s the choir members’ loyalty that helps it stay afloat.

“The art is such that once you get engaged in it, it’s very hard to leave. Those people can’t live without music, without singing, without this world of beauty. This world has become an integral part of their life.”