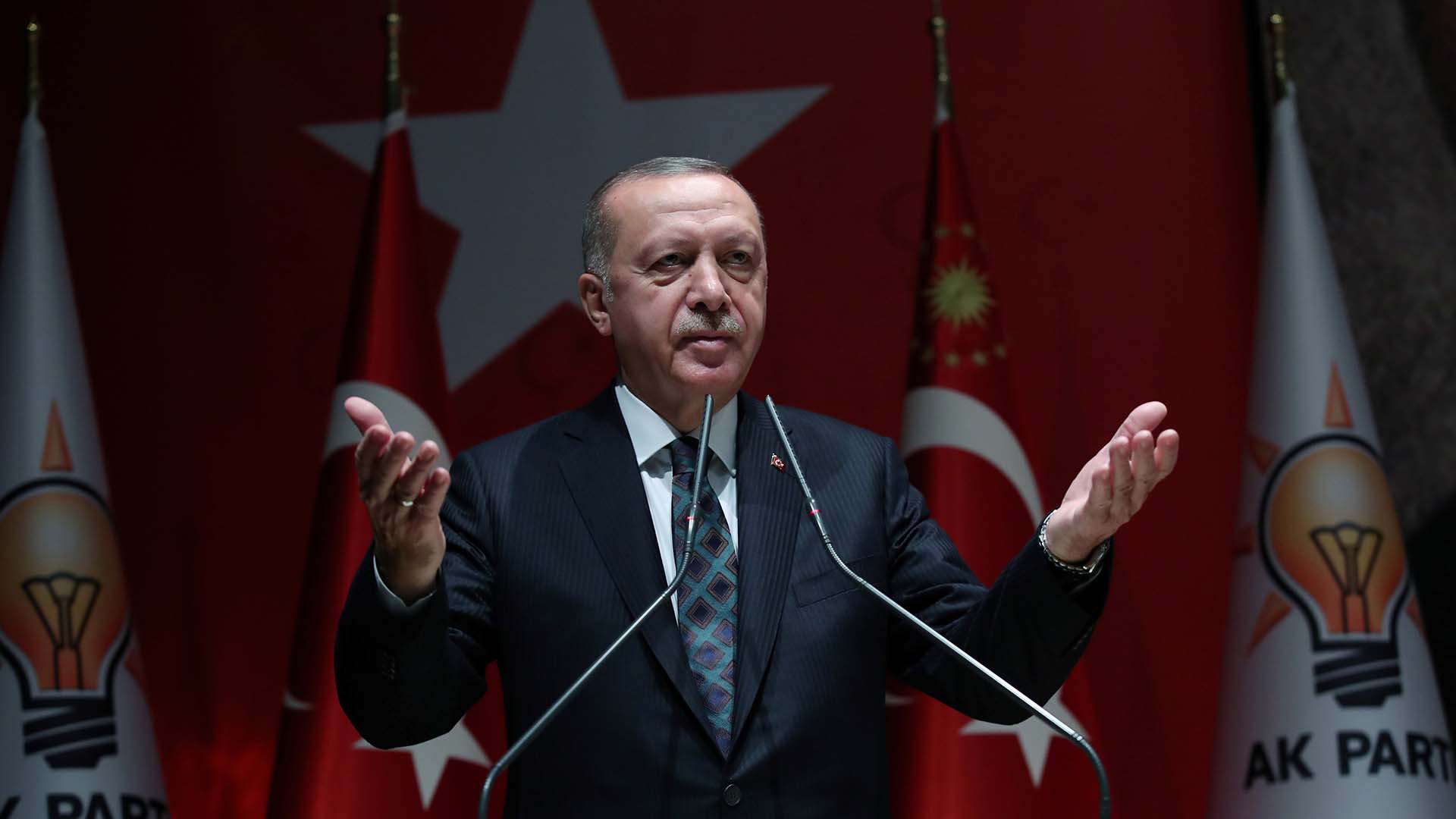

Sultan Erdogan: On the man who will again be Turkish President

Political biography of Erdogan

On May 28 Türkiye held the second round of presidential elections. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has been ruling Türkiye for twenty years, won more than 52% of the vote. His rival from the united opposition, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, 47% of the vote.

Thus Erdogan won the office for another five years in a country that, under him, has become richer and more influential, but less secular and free. During his twenty years of rule, he has managed to reduce the influence of the army on politics, increase the influence of Islam, and turn the country from a parliamentary republic into a presidential one. JAMnews partner Kloop looks back at how Erdogan came to power and changed Türkiye.

- Is Armenia ready to recognize the Treaty of Kars? Comments

- Will the catastrophe in Turkey change the country’s position in the South Caucasus? Comment from Baku

- Geopolitical shift in South Caucasus: waning Russian influence

Great Ottoman turn

Modern Türkiye became a secular state at the beginning of the 20th century thanks to the first president of the Republic of Türkiye, Mustafa Kemal, known as Atatürk (“father of all Turks”). He separated religion from the state and began to develop the country according to Western European standards, relying on the support of the army.

Atatürk liquidated the sultanate and established a republic, introduced the European system of weights and measures, European clothes, introduced the Gregorian calendar and 24 hour-day, purged the language of Arabic and Persian borrowings, and established the Latin alphabet for Turkish. Among Atatürk’s reforms are the introduction of universal secular public education, giving women the right to vote, the replacement of Sharia law with the Swiss civil code, and the abolition of polygamy.

Nevertheless, political Islam in Türkiye not only survived, but remained popular with a significant part of the elite. Although attempts at conservative and religious revenge were suppressed by the army (five military coups occurred in Türkiye from 1960 to 2016), Atatürk’s opponents retained their positions in the Turkish elite and periodically regained power, criticizing the Kemalists for their lack of spirituality and denial of the foundations of Islam. One of them was Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

He began his career in politics in the mid-1970s in Istanbul, heading the youth cell of the Islamist National Salvation Party. A few years later Erdogan joined the Prosperity Party, which also adhered to the principles of political Islam. In its ranks, Erdogan first became known as an orator and public politician — his appeals to the Turks, disillusioned with Kemalism, quickly became popular.

In 1994 Erdogan became mayor of Istanbul, and a year later the Prosperity Party entered parliament. But in 1997, the military forced former Prime Minister of Türkiye and head of the Prosperity Party, Necmettin Erbakan to resign. The party and its supporters were accused of anti-secular activities and a long-term attempt to create an “Islamic state” in Türkiye. In 1998 the Constitutional Court banned the Prosperity Party for violating the principle of separating religion from state.

However, Erdogan continued to participate in conservative rallies. In 1997 he was accused of “inciting religious hatred” for quoting the poems of Pan-Turkic ideologist Ziya Gökald. Erdogan was removed from his post as mayor and imprisoned for four months.

Four years later Erdogan became co-founder and chairman of the Justice and Development Party. In November 2003 the party entered parliament and received the majority of mandates, allowing it to form a one-party government. At the beginning of next year, the parliament loyal to Erdogan changed the laws so that a criminal record would not prevent him from assuming the prime minister’s chair. In the spring of 2003 Erdogan became a deputy, and soon the president appointed him prime minister.

Thus began the longest conservative turnaround in the last 100 years in Türkiye, with some claiming it all to be an attempt to gently recreate the Sultanate and the Ottoman Empire, both in the country and out.

Forward to the past

Like Vladimir Putin, another “rebuilder of empire” and zealot of “traditional values”, Erdogan was very lucky when he came to power. The first decade of the 21st century has been a period of unprecedented boom in the markets of developing countries. The dot-com bubble that had been inflating the global economy since 1995 burst, and in search of new growth points, global investment banks began to invest hundreds of billions of dollars in peripheral countries, including Russia and Türkiye.

Raw material prices began to beat all conceivable records; the largest countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America were choking on money. Some of this wealth also fell to the population, whose incomes grew. And local politicians surfed on the wave of this boom, saying that the people were getting richer from their brilliant decisions.

It cannot be said that the economic growth in Türkiye was the merit of the Erdogan government. The monetary reform carried out by it in 2004-2005 led to a decrease in inflation. They attracted foreign investors and spared no expense in the construction of large-scale infrastructure projects.

In 2005, on a wave of optimism that had swept the country, the Erdogan government decided to fulfill the dream of the late Ataturk and began negotiations on Türkiye’s accession to the European Union. For a conservative-religious politician who has opposed the pro-European ideology of the Kemalists since the 1970s and even went to prison for it, this was an obviously illogical step. Nevertheless, Erdogan fought the cautious European bureaucrats like a lion, provoking them into sharp refusals and attacking them with angry criticism.

Today many consider these negotiations a spectacle. Erdogan could not help but know that the EU is not ready to accept such a dissimilar country as Türkiye into its ranks. And he used the inevitable refusal of Europe to compromise the ideas of Ataturk and legitimize in the eyes of Turkish society a further turn towards “neo-Ottomanism” and pan-Turkism.

Signs of Türkiye’s departure from the European path began in the first half of the 2000s. Human rights activists announced the curtailment of freedom of speech in Türkiye and persecution under the article “insulting Turkish statehood”. Among those accused were the writer Orhan Pamuk, a future Nobel laureate who was forced to emigrate, and journalist of Armenian origin Hrant Dink, who was killed in 2007.

Erdogan resets to zero

In 2007 presidential and parliamentary elections were to be held in Türkiye. According to the laws, the president of the country was elected by the parliament. Erdogan’s party nominated Abdullah Gul, his deputy and former party member in the Prosperity Party, for this post.

The Kemalists opposed it in parliament because they considered Gul’s religiosity a prelude to the Islamization of Türkiye. Protests were held in large cities. The protesters were supported by the chief of the General Staff of the Turkish army, promising that the army would help them defend the secular state. This prevented Gul from becoming president, but not for long.

Erdogan’s party again won the parliamentary elections — in the wake of continued economic growth, it again received more than half of the deputy mandates. The new parliamentarians successfully elected Abdullah Gul as president, and this time the army promised not to interfere.

Later, the Turkish Prosecutor General’s Office tried to ban the activities of Erdogan’s party, for an alleged conspiracy to create an Islamic state. But the Constitutional Court did not uphold this claim.

Two years later, an event familiar to residents of many post-Soviet countries took place in Türkiye — with the help of a referendum, the country’s Constitution was changed. This allowed Erdogan’s party to extend its rule for a third term. But the amendments also affected the power bloc; the military lost immunity in civil courts, which for decades had helped them defend Türkiye’s Kemalist foundation. This later led to the arrest of officers accused of plotting a military coup against Erdogan’s party.

In addition, under the new constitution the president would be elected not by parliament, but by general elections. And in 2014, Erdogan was elected president. Initially, this was a decorative position, as all important decisions were made by the prime minister and his government. Although this did not prevent Erdogan from influencing the actions of the government and his associates in parliament. But over time, he turned the powers of the president into truly royal ones. More precisely, the Sultans.

Defeating the military and establishing autocracy

On the night of July 15, 2016, a military coup attempt took place in Türkiye, weakening the position of the Kemalists and strengthening Erdogan.

The soldiers occupied the bridge across the Bosporus, the General Staff building and seized the central television channels, saying that power had passed to them. They launched an airstrike on the parliament building in Ankara. But by morning the putsch was crushed. As a result of the clash between soldiers and supporters of Erdogan, about 300 people were killed, and about 1,500 injured.

Tens of thousands of people were arrested or suspended from work for their role in the coup attempt and for “lack of loyalty” to President Erdogan. Among those arrested were soldiers, teachers, judges, and journalists. Authorities blocked access to more than twenty news websites, revoked the licenses of 25 publishers in the country, and issued arrest warrants for 42 journalists.

Former imam and preacher Fethullah Gülen, who has been living in the United States since 2000, was accused of attempting a coup by the Turkish authorities. He is considered the second most influential person in Türkiye after Erdogan himself, and insists that Islam and democracy are compatible. His influence rests on a system of lyceums in 150 countries, and in Türkiye on a network of supporters in the army and police, whom Erdogan calls “a state within a state.”

Erdogan demanded the extradition of Gülen by the American authorities, but was refused and is now persecuting the imam’s supporters around the world.

In 2017 the Turkish authorities also demanded that Kyrgyzstan close the Sebat lyceums, which were associated with Gülen. The Kyrgyz authorities asked Türkiye not to interfere in the country’s internal affairs, but renamed the lyceums “Sapat”. Four years later, the Turkish authorities kidnapped the president of the network of these lyceums, a citizen of Kyrgyzstan and a native of Türkiye, Orkhan Inanda, in Bishkek.

In 2017 Erdogan also again changed the constitution, making the parliamentary republic presidential. The government, the election commission, the courts, the police and the army had to obey the president. The post of prime minister, which Erdogan himself held for about ten years, was abolished. Türkiye thus became an autocracy.

Citizens went to rallies for the revocation of the referendum on changing the constitution, but could not achieve what they wanted. A year later, Erdogan was re-elected president and became the de facto sole ruler of Türkiye.