Five main Russian myths about Crimea and how they work

Myths about Crimea

“Ancestral Russian land,” the Kremlin says about Crimea. And the Russian people shouted enthusiastically in 2014: “Crimea is ours!” For many years before that, people there had been accustomed to the idea of Russian Crimea, from school history courses and television to free vacation trips to Yalta.

After the “return to home harbor,” these myths, instead of preparing the ground, began to work to justify the occupation. And to the historical myths were added new, political ones. Moscow is trying to spread them all over the world. So refuting the Kremlin’s narratives about Crimea is Ukraine’s weapon in the fight for the opinion of the international community.

Article by the independent Ukrainian publication “Zaborona”

How Russian myths about Crimea work

The purpose of creating historical and political myths about Crimea is obvious: it is to justify why Russia has the right to the peninsula.

“If you tell children at school that white is black and black is white, then, of course, a person will say: ‘We were told that we read it in textbooks, in historical literature. It’s embedded in the subcortex,” says Gulnara Abdulayeva, a historian and author of several books on the history of the Crimean Khanate.

How are historical myths created? A completely true fact is taken, covered partially, from an angle favorable to Russia, and important details that are unfavorable are omitted, explains Elmira Ablyalimova, project manager at the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies.

“If you come to a region without having the right to it, you have to invent this right to be, live, dominate, and develop here. Today’s Russian authorities are still acting on the model of the first occupation of Crimea in 1783. Back then, they said that the Crimean Tatars, the “Basurmans,” were oppressing Christians in Crimea. What they wanted was to dominate the Black Sea region. Because at that time, access to the Black Sea was Russia’s most important political goal,” says Elmira Ablyalimova.

She also notes that the purpose of creating historical myths is to construct an idea of Muscovy’s involvement in some great history: first the Golden Horde, then antiquity through the alleged continuity from the Roman Empire through Byzantium (Eastern Roman Empire) — hence the concept of “Moscow is the Third Rome.” The same applies to Muscovy’s appropriation of Ukrainian history, including the name of Rus.

Crimea is a sacred place

Myth 1. Crimea is a sacred place for Russia, because Christianity came to Russia from there through the baptism of Volodymyr the Great, so the Crimean peninsula, including ancient Chersonesus, must be part of the Russian Federation.

“Crimea is the gateway to Christianity” is the slogan, as we would say now, of the conquest of Crimea during the time of Empress Catherine II. After all, according to Russian historiography, it was in Chersonesus that Volodymyr the Great, Prince of Kyiv, was baptized

“Prince Volodymyr was not baptized in Chersonesus,” believes Serhiy Hromenko, Ph.D. in History, author of the book “Crimea Is Ours. The history of the Russian myth”. For more than a hundred years, historians have reached a consensus that the prince was baptized before the campaign to Crimea, either in 987 or in January 988. There are still debates about the place of baptism, whether it was Kyiv or Vasyliv (now Vasylkiv), but this is not so important. The main thing is that the campaign to Chersonesus was a purely political event, in no way connected with Prince Volodymyr’s spiritual quest.”

Christianity really first appeared on the territory of modern Ukraine in Crimea, back in the third century AD. The Goths who lived in Crimea at that time were Christians, but it was Arian Christianity, recalls historian Gulnara Abdulayeva. The cave monasteries of Crimea are of the Arian heritage. Later, the Goths mixed with the Hellenes, but the influence of Arianism persisted for centuries, until the first occupation of Crimea by the Russian Empire.

The age-old enmity between Crimea and Ukraine

Myth 2. The Zaporizhzhia Cossacks have been at war with the Crimean Khanate for centuries, but could not defeat it. The conquest of Crimea by the Russian Empire fulfilled the aspirations of the fraternal Ukrainian people for a safe life. Therefore, Crimea, tamed for a good purpose, must belong to the Russian Federation today.

Crimea and Ukraine are united not only by geography but also by long-standing relations dating back to the Cossack era and earlier. According to historical sources, the union of the Cossacks and Crimean Tatars was not hindered by differences in religion or language. They have a history of fierce enmity and betrayal, but there are also facts of successful alliances, such as one of the most famous, the alliance between Bohdan Khmelnytsky and the Crimean Khan Islam III Geray.

“Since the late 15th century, ties between Crimea and Ukraine have been strong and continuous, although not always satisfying for both sides,” says historian Serhiy Hromenko. “On the one hand, Ukrainian lands were the scene of military invasions by the Crimeans, and Ukrainian prisoners were sold year after year in Crimean markets. On the other hand, Ukrainian Cossacks regularly attacked the Crimean coast, also taking prisoners.”

2. Portrait of Islam Geray III, author unknown.

The relations, adds historian Gulnara Abdulayeva, were not warm from the very beginning of the 16th century, but this did not prevent them from having peaceful economic ties with their neighbors and, if necessary, from uniting for joint military campaigns. “The 1521 campaign of the Crimean Khan Muhammad Geray I, in which Cossacks led by Yevstafiy Dashkevych took part, is very indicative. We know that before that, Yevstafiy Dashkevych had not had very good relations with the Crimeans. But when the Crimean Tatars had a confrontation with the Moscow prince, they united and marched on Moscow. The campaign was very successful for the allies,” the researcher notes.

She recalls the support provided by the Cossacks to the Crimean Khanate during the invasion of the Nogai army in 1523, the participation of Zaporizhzhia in suppressing the internal rebellion against Khan Saadet Geray, and the participation of the Cossacks in the military campaigns of the Crimeans to Iran and Hungary, and in battles with the Ottoman army.

“Ukraine and Crimea were closely linked by the historical past: war and politics, economy and culture,” says Gulnara Abdulayeva, “the same system of relations, broad self-government, full religious freedom, similar economic culture, and a common view of property and international law. We were united by the ethnopsychological proximity of the Sich and the Crimean Khanate, which had a warrior mentality. Therefore, it is unsurprising that military alliances often existed between the Cossacks and the Crimeans, and each time the ties became stronger.”

The myth of the eternal enmity between Crimea and Ukraine is perhaps best disproven by the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk, notes Elmira Ablyalimova of the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies. Pylyp Orlyk defines the relationship between the Cossacks and Crimean Tatars with the word “brotherhood.”

“It seems to me that this is the best demythologizing example of how our ancestors saw the future, taking into account all these complex processes,” Ablyalimova believes. “Because they lived on a territory that was encroached upon by everyone, both from the west and from the east. They saw that only in brotherhood could they preserve themselves, and this is extremely important.”

Khrushchev gave Crimea as a gift

Myth 3. Mykyta Khrushchev gave Crimea to Ukraine illegally, out of his sympathy for the Ukrainian SSR. Therefore, the return to Russia is legal and restores historical justice.

The scandalous new Russian history textbook edited by Vladimir Medinsky states that Crimea was transferred to Ukraine on the personal initiative of Mykyta Khrushchev, the first secretary of the Communist Party Central Committee.

Two days after the so-called referendum in Crimea, Russian President Vladimir Putin delivered the infamous Crimean speech, finally tying the topic of Crimea to Khrushchev: “The initiator was personally the head of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Khrushchev. What motivated him to do this — the desire to enlist the support of the Ukrainian nomenclature or to atone for his guilt for organizing mass repressions in Ukraine in the 1930s — let historians deal with this.”

So let’s turn to historians. After 1944, when the Crimean Tatars were expelled from the territory of Crimea, about 500,000 people remained on the peninsula. Crimea became virtually deserted. But not for long. We know that the Soviet government set the task of making Crimea “new” with its Russian way of life, and in the fall of 1944, the first immigrants from Russian regions and republics began to arrive there.

“They just destroyed our Crimea because they did not know how to manage the economy,” describes the background to the transfer of the peninsula to Ukraine historian Gulnara Abdulayeva. “There were many springs, deep wells, fountains, beautiful gardens in Crimea — it was a rich land, everyone wondered how Crimean Tatars could grow gardens and orchards in the mountains… Newcomers moved into the homes of Crimean Tatars. They did not go to the forest for firewood, for example, but cut down fruit trees that grew nearby. And in 10 years, they turned Crimea into a waterless desert, where it is very difficult to live.”

By 1952-53, the situation in Crimea was simply catastrophic. Something had to be done, the Soviet government had to correct its mistakes. That’s when Mykyta Khrushchev proposed resettling to Crimea Ukrainian peasants who knew how to farm in the Northern Black Sea region.

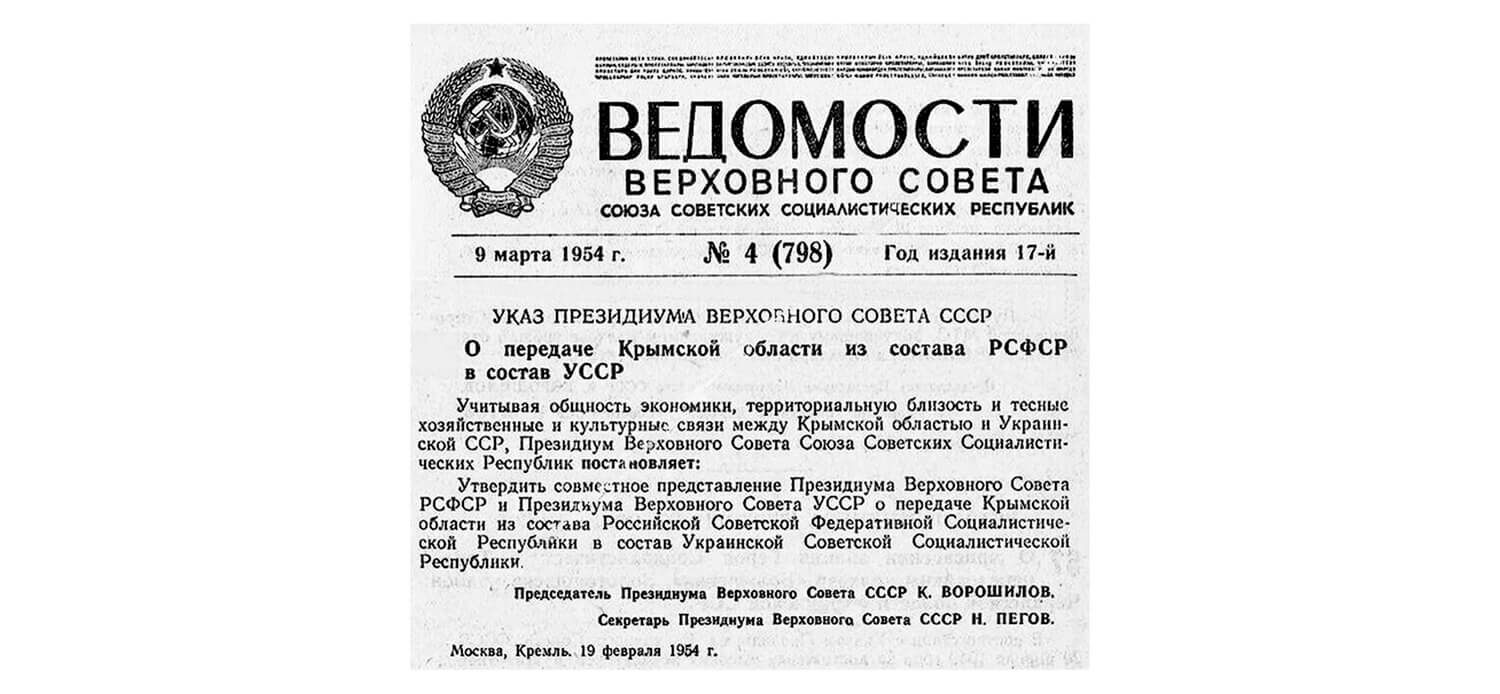

However, the transfer to the Ukrainian SSR did not happen overnight, nor did it happen at Khrushchev’s command. The decision was discussed and made collectively with the head of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, Kliment Voroshilov, the head of the Council of People’s Commissars, Georgy Malenkov, and the rest of the Politburo.

First, at a meeting of the Presidium of the Central Committee on January 25, 1954. Then, on February 19, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree on the transfer of Crimea to the Ukrainian SSR. But that was not all: only in April 1954 did the Supreme Soviet of the USSR legalize this decree at a session. Legally, the process of transferring Crimea ended with amendments to the USSR Constitution and republican constitutions.

“In the Russian public consciousness, all the ‘mishaps’ that occur during the reign of a ruler are blamed on him,” summarizes Serhiy Hromenko, PhD in History. “So Khrushchev was made responsible for all the failures in the Soviet Union during ‘his’ period: for corn and excavated virgin lands, as well as for Crimea. He was made responsible by a political decision in the 1990s. Inside the Soviet Union, no one would have thought to blame Khrushchev for handing over Crimea to Ukraine. He was just unlucky.”

Referendum in March 2014

Myth 4. The referendum held in March 2014 was representative, and its results reflected the moods and aspirations of Crimeans, who overwhelmingly wanted to join the Russian Federation. It was completely legal, as it was the will of the citizens of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

The argument about the expression of will in the Crimean “referendum” of March 16, 2014, is used primarily when people want to emphasize the alleged legality of the annexation of the peninsula. As if by doing so, Crimeans themselves decided to control their destiny, to return “to the bosom of Russia” and restore historical justice.

However, according to current Ukrainian legislation, local plebiscites are not legally allowed. According to paragraph 2 of part 3 of Article 3 of the Law of Ukraine “On All-Ukrainian Referendum,” a ratification referendum on changing the territory of the state may be held following the results of an all-Ukrainian expression of will. This clause alone would be enough to prove the illegality of this action. But there are many others.

On February 20, Russia launched a special operation to seize the peninsula. It has been flooded with Russian military equipment and armed men in uniforms without any insignia — the so-called little green men. The carefully planned special operation is evidenced by the medals minted in Russia that were awarded to the participants in those events. On the reverse of the award is an inscription with dates: “For the return of Crimea 20.02.14 – 18.03.14”. That is, even before the organization of the “referendum” on the status of the peninsula, Crimea was being actively “returned”.

“In the decision regarding the admissibility of the complaint in the case “Ukraine v. Russia (regarding Crimea)”, the European Court of Human Rights recognized the application submitted by Ukraine as partially admissible,” says Tamila Tasheva, the Permanent Representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, human rights activist. This case highlights the importance of the Russian Federation’s systematic violation of the European Convention on Human Rights in the occupied Crimea, including the fact that such violations were carried out by officials of the Russian Federation as “administrative practice.” Initially, the Court determined the scope of the case and ruled that Russia began exercising military control in Crimea on February 27, 2014. That is, it is a military seizure of our territory, the occupation of the peninsula.”

Andriy Klymenko, project manager at the Black Sea Institute for Strategic Studies, recalls: “For us, those who lived in Crimea at the time, the date of the beginning of the occupation was the morning of February 27, when Russian military and armored vehicles appeared on the streets of Crimea and the buildings of the Crimean government and the parliament of the autonomy were seized.”

The Russian military then blockaded the Supreme Council of Crimea, the airport in Simferopol, the Kerch ferry crossing, Ukrainian military units, and strategic facilities on the peninsula. Behind closed doors, the then Prime Minister was removed from office and a “referendum” was called. Its date was postponed three times.

“On the night of March 15-16, one of the last units was stormed. The Russian Forces came to my husband and said that tomorrow was the last day I could be allowed to leave, otherwise, no one will find me,” says Olha Skrypnyk, head of the board of the Crimean Human Rights Group, co-coordinator of Euromaidan in Yalta. “At that time, my colleagues had already been abducted [the editor-in-chief of the Crimean Svitlytsia newspaper, Andriy Shchekun, and the head of the Board of Trustees of the Ukrainian school-gymnasium in Simferopol, Anatoliy Kovalsky, were illegally detained and tortured].”

On March 16, 2014, Russians launched a so-called referendum in Crimea and Sevastopol. There were two questions: on the restoration of the 1992 Crimean constitution and Crimea’s accession to Russia. The ballot provided for an answer to only one of the questions, any mark was interpreted as a “yes” answer, and two marks made the ballot invalid. There was no option to leave the status of Crimea unchanged.

“The Crimean referendum has historical parallels — this technology was used in Austria and the Sudetenland in 1938, during the occupation of Northern Cyprus in 1974. What did Putin do? He repeated the historical precedents when they tried to legalize the seizure of territories through a referendum,” says the lawyer and co-author of the report “Crimean Precedent. Imitation of Democracy” Serhiy Zayets, an expert of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union.

According to international law, the presence of foreign troops on the territory of a country makes it impossible to express the will of the people, so such a plebiscite is ignored by foreign observers. Even though the results of the so-called Crimean referendum in 2014 were not recognized by most countries, it was the beginning of an open occupation.

Crimea is a separate issue, as well as Donbas

Myth 5. Crimea’s return home is a thing separate from the events in Donbas because it took place without violent confrontation through a referendum. That is why the issue of Crimea was not discussed either in the Normandy format or at the talks of the trilateral contact group in Minsk. Because of this, we cannot talk about the beginning of the Russian war against Ukraine in February 2014.

This is perhaps the least obvious of the myths about Russia’s occupation of the Crimean peninsula. Even those who have been talking about the war since 2014 have said that the war began in April with Sloviansk, and they called the Russian war against Ukraine the “war in Donbas.” And this was an unconscious imitation of Russian narratives that separated the occupation of Crimea from the “war in Donbas.” All negotiations on the conflict settlement were exclusively about Donbas, leaving aside the issue of Crimea as Putin’s “red line.”

“This constant unwillingness to call itself a party to the conflict and the attempts to separate the Crimean case and the case of the occupied territories of eastern Ukraine — yes, this was Russia’s position, which was completely shattered during the attack on Ukrainian ships heading to Mariupol in November 2018 in the Kerch Strait,” says Mariya Kucherenko, an analyst at the Come Back Alive Foundation. — “Because it has already become obvious that there is no separate Donbas, no separate Crimea, and all this is one aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine.

Ukraine’s partners, the mediators within the Normandy format — France, Germany, and the United States as the main ally — found themselves in a certain deadlock. It was constantly being said that the Minsk agreements were the only basis for a settlement.

“And it was a separate difficult track to explain that it was all one aggression,” says Mariya Kucherenko. “And that the previous beliefs that the Minsk agreements would be the only basis for a settlement and would not include the issue of Crimea would have to be abandoned one way or another.

As history has shown, the Minsk agreements indeed have to be abandoned. However, not in 2018, when the attack on Ukrainian ships made it clear that no settlement would be reached. But when Russia decided to recognize the pseudo-republics in eastern Ukraine in 2022. Although the Minsk Agreements do not mention any pseudo-republics: they only refer to certain districts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

“It was a separate part of our (as a party) struggle against the Russian Federation to unite the artificially divided elements of Russian aggression against us and explain it to our partners,” says Mariya Kucherenko.

According to Elmira Ablyalimova of the Crimean Institute for Strategic Studies, the events in eastern Ukraine were largely intended to divert the world’s attention from Crimea. At the same time, she notes that some in the West believed that in the end, Russia would limit itself to occupying Donbas after seizing Crimea.

“In 2014, when I was still in Crimea, a journalist from Europe told me: “Once Russia has captured Crimea, it will capture Luhansk and Donetsk regions and be satisfied, they don’t need anything else.” And I remember very well drawing him a map of Ukraine with Crimea and Donbas, where these proxy bodies of the LNR and DNR had already been created, and I said: “They need a land corridor, all this territory, to dominate the Black Sea,” recalls Elmira Ablyalimova. “And the newly occupied territories, if you look at the map, fully confirm my words at the time.”

How to counter Russian myths about Crimea

Historical myths, unfortunately, cannot be overcome by rational arguments, because they cling to emotional perception, says historian Serhiy Hromenko.

Contemporary Russian mass culture offers dozens of films, TV series, and books that place Crimea at the center of Russia’s geopolitical interests. These include historical works depicting Empress Catherine II and the present day. All of them are designed to reinforce historical and political myths in the minds of Russians, touching them emotionally.

“What Russian propaganda broadcasts to the Russian audience today does have a great impact on people. But if tomorrow we switch the lever, change the picture for the Russian audience, then in a very short time they will stop believing that they really need Crimea and that this is how Russia’s geopolitical will is asserted in the world,” said Mariya Kucherenko, an analyst at the Come Back Alive Foundation.

It is more difficult to fight myths that are enshrined in historiography. Because since the times of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, they have been rooted in thousands of scientific works that create a global, supposedly socially recognized context. Simply because the topics of historical research in the USSR were approved as part of the official history course introduced by Moscow.

“Just telling how things really were. With evidence, with primary sources. But first, we need to clean up our historiography,” says historian Gulnara Abdulayeva.

This really needs to be done, but the most important point seems to have been made by Mariya Kucherenko of the Come Back Alive Foundation: no historical justification can justify violating the principle of territorial integrity: “In general, it is wrong to engage in a conversation about ‘who lived there in what centuries’, ‘who owned Crimea’, ‘what peoples lived there’ and draw some conclusions from this, as Putin did in his annexation speeches. No. We have to talk about the principle of territorial integrity. There is an attempt to violate the world order that existed after the Second World War by the fact that the Russian Federation has annexed our territory. This is what we have to talk about, not about some inventions of homegrown geopoliticians like Alexander Dugin or Channel One producers.”