Armenia’s Metsamor power plant and people who live around it

Armenia’s Metsamor power plant

A man got out of a brown Soviet ‘Moskvich’ and headed towards me. Smiling broadly, he stretched out his hand to me and said: “Hello, I’m Felix, one of the employees of the nuclear power plant. I was me, whom you talked to on the phone. How did you get to Metsamor? Transport no longer runs here from Yerevan. Instead of answering his question, I pointed towards a driving away taxi.

Felix Martirosyan, 68, had spent 44 years of his life at the nuclear power plant, dealing with radiation inactivation. I noticed him limping slightly, which he explained by decades-long work at the nuclear power plant, and, to cap it all, he was experiencing problems, caused by involvement in the rescue operations in Chernobyl.

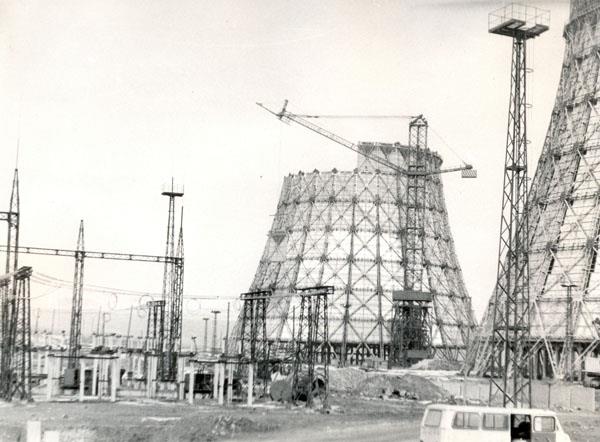

We drove in Felixe’s oldtimer ‘Moskvich’ though one of the youngest and most important towns in Armenia, located at a 36-kilometer distance from Yerevan. The town, or to be more precise, the nuclear power plant that is operating here, generates 40% of the overall electric power, produced by the country. Three cooling towers and the smoke coming therefrom, that could be seen from any part of the town, have long become the town’s landmarks.

Having cast a glance full of regret at the power engineers’ town, Felix said: memories are the only thing left from once-busy Metsamor. Everyone had a job here some 30 years ago.

He pointed to one of the residential districts and said: in due time, there was cabin district that provided accommodations to the specialists, who arrived in Metsamor from different Soviet republics.

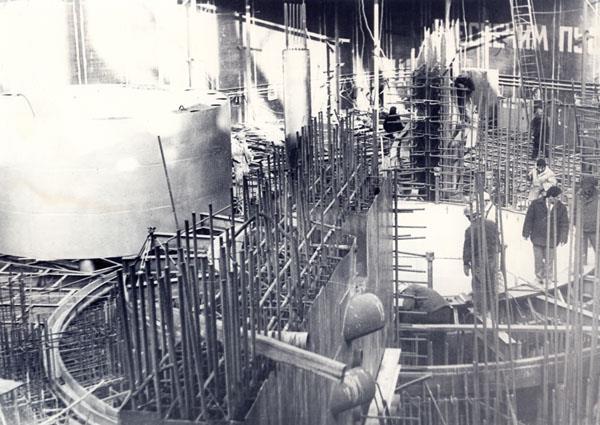

“The construction of town was launched parallel to construction of the nuclear power plant. The plant personnel was gradually provided with housing. I got an apartment in 1972, said Felix, the father of 2 sons and the grandpa of 6 grandchildren.

One of the persons accompanying Felix, Yura Invinyan, 70, who had worked at the Metsamor nuclear power plant for 35 years, recalled: there were dormitories in those two building in 1925-26, one for the women and another one – for the men.

“It was in 1978. There were dance parties here on weekends….The women came from Murmansk to work here – Marusya, Sasha, Katya…many of them got married here. Some of them left the town after the collapse (of the Soviet Union). However, some Russians still live in Metsamor, says Invinyan.

Photos from HAEKSHIN construction company website

Changes that took place in Armenia over the past 25 years have influenced Metsamor town. Only 20% of the overall 10,665 residents of the town are employed at the nuclear power plant nowadays. Robert Grigoryan, Metsamor town mayor, pointed out that the town didn’t belong to the nuclear power plant. Since 1992, the town has its own local government bodies.

Felix stopped his car at one of the daycare facilities, where the young staff of the “Huys Metsamor (Hope of Metsamor) organization had gathered. In due time, their parents used to work at the nuclear power plant. They still remember their international town and the active life in those years.

Varditer Hovhannisyan, 28, who holds a degree in speech-language therapy, admits, she misses a whistle of the Metsamor train, that delivered the nuclear power plant personnel from Armavir and the neighboring villages every morning:

«We were looking forward to that whistle every morning. When the train stopped at the station, a great flow of people headed towards the NPP. Now, as I recall all that, it’s like film stills. There was certain romanticism in that, some soviet recollections. I wish, it could be the same way now. Train was the town’s main artery, but it no longer exists, regrettably, not.

Huge yellow oranges and Coca-Cola (Metsamor was the only place in Armenia, where it could be found in Soviet times) are the most vivid memories that Haykanush Harutunyan, 38, a social teacher, has preserved until now:

“My parents worked at the NPP and, like many others, we were using special cards, allocated to the NPP personnel. My parents said, all the products: butter, meat, canned food and fish, were delivered there from Moscow. There was so much of everything that we even distributed foodstuffs among the relatives. We could buy a pair of jeans for RUB80-90, while they cost RUB200 in a consignment store, or, let’s say, the well-known Salamander brand footwear.

In her words, a few years ago, before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Metsamor had been a town with particular status and high living standards, but one can’t say the same thing about it now.

“Metsamor resembled a mosaic, bringing together the intellectuals, representatives of all kinds of nations. It was a collective, motley town. People, who came here from rural areas, were integrating into the urban life and starting development. The Russians, Ukrainians and Belorussians brought here their own culture. I miss that intellectual environment, said Haykanush.

Felix said, his friends had already gathered and were waiting for us. So, we hurried to Felix’s cottage, located inbetween the city and the nuclear power plant.

“Here are our summer cottages. In Soviet times, the state allotted those land plots to the NPP personnel and we built a house and planted an orchard here. Many of our guys spend their summer days here. See, there is a town on one side and the nuclear power plant-on another side, said Felix.

There were orchards stretched outside the lined up houses. “Moskvich” engine gradually subsided- we finally arrived. Felix’s colleagues were waiting for us in the garden outside the cottage.

Some of them no longer work at the nuclear power plant. They admit, Soviet times were the best years in their lives. The past 25 years was a period of their survival, a struggle for a more or less secured, comfortable life.

Hovsep Danielyan, 62, a dose monitoring technician, has been working at the NPP for 40 years already. He took part in the launch of the first and second energy units. Today, his son also works as a dose monitoring technician.

“I used to work under particularly hazardous conditions for 35 years. My salary now amount to AMD 200,000 (US$ 421). I will retire in 2 years and will get AMD40,000 (US$ 84). We will have to solve many social and economic problems on that money, and this despite the fact that we’ve lost our health here. In Russia, the people of our profession receive disability benefits along with their ordinary pension, Danielyan said indignantly.

According to the NPP personnel, in Soviet times, the income tax wasn’t deducted from their salaries; they had 50% discount on electricity bill payments; the NPP trade unions covered their summer vacation costs. Everyone notes with regret that country’s independence has deprived them of many privileges, and that’s against the background that all of them worked in particularly hazardous conditions and now they are the 2nd or 3rd-degree disabled persons.

“Money has changed and our salaries have changed too. In Soviet times, apart from the salary amounting to RUB120, I also received RUB1,300 allowances, because that work turned me into a 2nd-degree disabled. Whereas now, I get only a pension amounting to AMD80 (US$166). My 4-memeber family could have easily traveled on vacation to the Crime for RUB 1,300, said 70-year-old Inviyan, who used to work as the NPP senior foreman.

Like in many other Armenian towns, the male residents of Metsamor also leave the town to find jobs in Russia. Many NPP employees traveled to Iran and Russia for several years running, to work at the local nuclear power plants.

They are discontent with the fact that the Armenian NPP personnel has the lowest income in the post-Soviet area.

“Many of our fellows, the high-skilled specialists, are now in Russia. And the only reason for that is high salary. People there earn up to US$1,200, whereas here – AMD80-100 (US$168-210). In Russia, the participants in Chernobyl rescue operations are paid RUB2million; do whatever you want. We also took part in them and are still facing the consequences of radiation exposure. Our health condition has been getting worse from year to year, but we are completely neglected, said Hovsepyan, a dose monitoring technician.

Misha Nazaryan, 66, says, he participated in the energy unit construction works in Iran, in 2010-2014. He was paid US$2,000 per month for his job:

“We used to work in Bushehr, at a 1,300km distance from Teheran. It’s the country’s hottest location. There were about 100 Armenian specialists, who had been earlier employed at the NPP. It’s a pity that the work finished. If I have such a chance, I will go there again.

The residents of Armenia’s youngest town hope that either the aged NPP will continue its operation, or a new one will be built in its stead. It’s necessary to prevent outflow of youth from the town.

An agreement, under which Russia will provide Armenian government with a loan for extending the service life of the Armenian nuclear power plant, was signed in Moscow in February this year. According to the document, the Russian side will provide Armenia with US$270million preferential loan, as well as a grant amounting to US$30million.

Extending the service life of the available energy unit will allow the Armenian authorities to gain time for raising funds for construction of a new NPP.

Yervand Zakharyan, ex-Minister of Energy and Natural Resources of Armenia, stated earlier, the capacity of a new NPP unit should be 600MW, rather than 1,000MW. In his words, a smaller plant could operate in a more flexible mode and it could be easily connected to the general grid.

According to the early estimates, a 1,000MW NPP construction costs will amount to approximately US$6billion, while the construction of a 600MW NPP will cost about US$2,5-3billion, which certainly increases a probability that the Armenian government will manage to get the necessary amount.

A discussion around NPP, which unfolded in Felix’s cottage, couldn’t come to an end. Finally, I reluctantly said goodbye. Felix volunteered to see me off to the taxi-stand. “I wish there were jobs, so that our children wouldn’t leave the city and could stay with us, Felix said at parting.

The taxi was driving in the direction of the capital and Metsamor, that was left behind, was getting smaller and smaller. Only three towers of the aged NPP, resembling a beacon, were visible from afar. They are the reminders that the NPP is still operating so far.