Is Georgian language banned in Abkhaz schools?

Is Georgian language banned in Abkhazia’s schools?

Since the beginning of a new school year, schoolchildren in the Gali/Gal region of Abkhazia, where ethnic Georgians reside, no longer study in Georgian – the last, 11th, grades, which until now had such an opportunity, switched to the Russian language, thus completing the transition of the local schools to the Russian-language program, with separate Georgian language courses. This provoked a harsh reaction in Tbilisi, where the Abkhaz authorities were accused of “banning the Georgian language” and of ethnic discrimination.

JAMnews correspondents prepared a report from both sides of the conflict about how local schoolchildren study, how the language change affected them and their families, and what children and their parents think about the future.

Multilingualism of Gal schools. Report from Abkhazia

Marianna Kotova, Sukhum

Perfectly flat asphalt without potholes and cracks leads from the town of Gal to the village of Taglan [the local Georgian population calls the village Tagiloni – JAMnews], which is located in the lower zone of the border region. Most of the houses along the road are abandoned. There is not a single passerby. A little less than twenty kilometers, and we reach the village school, where we are met by a family of turkeys, peacefully perched on the school fence.

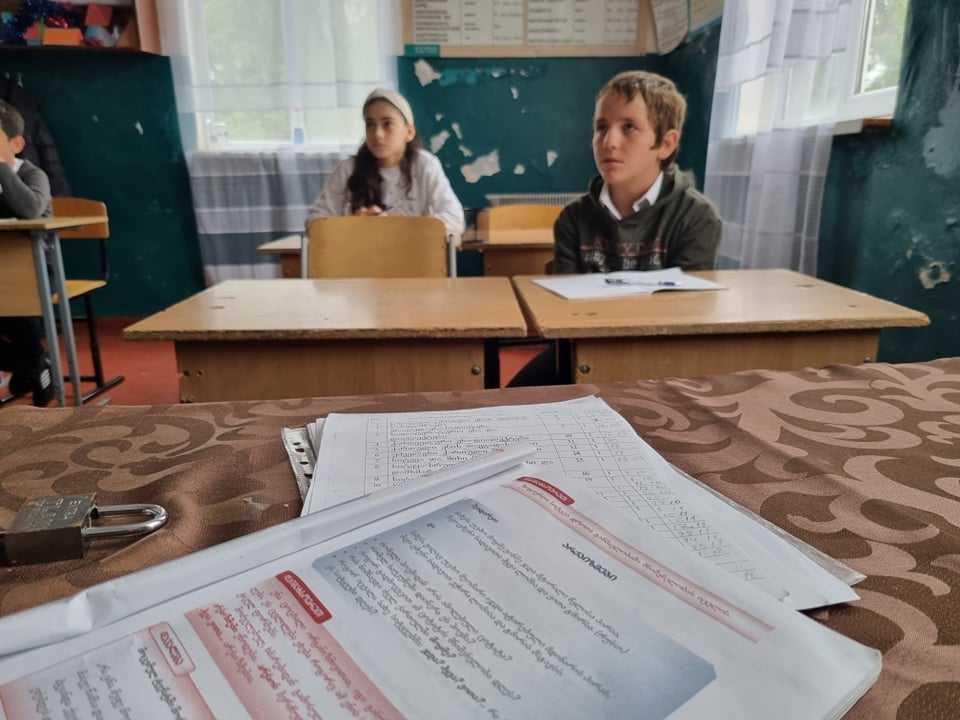

The building of the only Taglan school is quite large, a little too large for 89 students.

Now there is not a single parallel class here, and in Soviet times there were more than 50 students in the tenth grade only, says a graduate of this school and its current director.

This year, the 11th grades began learning Russian in accordance with the transition plan of 2015.

“The transition was carried out according to the following scheme – first the first grade, then the second and so on. The classes were systematically transferred from Georgian textbooks to Russian in all basic subjects, except for the native language and literature”, says the head of the district education department Yekaterina Gabelia.

- Op-ed: Does anyone want Georgian-Abkhaz conflict to be resolved?

- Re-examining the radicalizing narratives of Georgia’s conflicts

Today, all 18 schools in the Gal district of Abkhazia are considered Russian. 26 hours are allotted for the study of Georgian language and literature. Also, a compulsory subject of the program, as in all schools of Abkhazia, is the Abkhaz language – 28 hours are given to it. The rest of the disciplines are taught in Russian.

It cannot be said that children are infringed on their right to learn their native language, says Edisher Zukhba, director of a school in the village of Shashikuara, Gal district.

“There are three Georgian language teachers in our school. Children communicate with each other in their native language at home, there is no reason to believe that the younger generation will lose their language”, says the school director.

As for textbooks, school libraries in the Gal district, as well as throughout Abkhazia, are replenished only with Abkhaz educational material. Parents of schoolchildren have to buy Russian and Georgian textbooks

Schoolchildren and languages

There are students who do not know Russian at all, says Irma Kvaratskhelia, Russian language and literature teacher at a school in the village of Taglan.

“After all, they speak Russian only with us, teachers, at home and with friends, they only speak in Georgian”, the teacher says.

According to her, there are those who try very hard and cope with the difficult multilingual program.

“I even wonder whether they manage to successfully learn four languages and all other subjects while they are sleeping. But most of the children still experience great difficulties”, says Irma Kvaratskhelia.

As the teacher says, they do not read major works of Russian classics, but watch them instead. She asks her students to watch films, sometimes searches on the Internet and sends them short summaries of novels so that the children at least get an idea of what is written in the school curriculum.

As Irma Kvaratskhelia says, Gal schoolchildren have little motivation. They know that they won’t be able to build a life elsewhere in Abkhazia.

“Maybe I’ll say an unpleasant thing right now, but it’s true that in Sukhum and to the west of it we are treated differently from the rest of Abkhazia’s residents. Children themselves and their parents are wary of looking for prospects there. There were cases when our young people were mistreated in iSukhum”, says the teacher of the Russian language at the Taglan school.

The Abkhaz language is also difficult for Gal schoolchildren. With a strong accent, mainly softening and simplifying the complex sibilant sounds of the Abkhaz alphabet, second graders read the simplest text. Grammar is also difficult for them. The girl at the blackboard is trying to write the word Aiaair, there are more letters than sounds, and she gets lost in vowels, but this is the specifics of the language.

Lana Jopua has been teaching the Abkhaz language for two years at a school in the village of Taglan. Prior to that, the local students took this subject with long breaks.

“There were simply no teachers of the Abkhaz language here, they came from other districts, so it often happened that the teacher was physically absent from school”, says Lana Jopua. “This is felt very much by the children. They want to learn the language, I see this interest on their part, you just need to work with them correctly and regularly”.

According to the teacher, the most difficult thing for them is the pronunciation of individual throat and lip sounds.

Saba Mertskhulava is an eleventh grader. He speaks Russian with difficulty, but his vocabulary is quite rich. His dream is to master a profession in the field of international relations, but he has not yet decided where he will go.

Pupils, and especially older schoolchildren, are very attracted to English and, to some extent, Russian, as the knowledge of these languages opens up great prospects for rural residents.

“I will see where the quality of education is higher and where I can get in with my knowledge. Now I devote more time to English and Russian, as they are more widespread in the world than Georgian and Abkhaz, and for they are more useful”, says a student who has a theoretical opportunity to enter Tbilisi, Sukhum or a Russian university on a quota , which is provided for the citizens of Abkhazia by the Ministry of Education of Russia through the representative office of Rossotrudnichestvo.

There have been such cases, says Yekaterina Gabelia, head of the Gal Regional Public Education Organization (district education department).

The problem is lack of citizenship

According to Ekaterina Gabelia, none of the students or their parents is outraged, everyone calmly accepts the existing order, since children equally perceive all the languages they are taught at school. According to her, another problem is more acute – the lack of documents.

“Our children cannot get either Abkhaz passports, or even birth certificates”, says Ekaterina Gabelia. “If the graduates had documents, then much more of them would go to Abkhaz and Russian universities”.

In 2014, the issuance of Abkhaz passports to residents of the Gal district was stopped. For some time, the issuance of a residence permit was also suspended, so many residents of the region remain paperless or have Georgian passports.

This year, 233 students graduated from school in the Gal district, 17 of them entered the Abkhaz State University. There are also those who enter Russian universities, but due to the lack of Abkhaz citizenship, they have to stop their studies and return to their homeland.

“They waste time hoping that they will receive documents, study for a year or two with what they have, but then they end up going to Georgia. Everyone is accepted in Tbilisi with any kind of documents”, says Yekaterina Gabelia.

“In order for our children to have at least some perspective in life, they must know three languages: Georgian, Abkhaz and Russian. It is good to know a lot, but most of them will not be able to learn them properly, because this requires good textbooks and regular classes. We need tutors, which means money. A scanty number can afford it, and the rest will be ignoramuses who do not really any language”, says one of the mothers of the Gal schoolchildren.

“Generation without childhood”. What Georgian schoolchildren and teachers from Abkhazia say

Salome Partsvania, Zugdidi

JAMnews spoke with a student, her mother and a teacher from Gali about the situation in Gali schools and what translation of education into Russian means for them.

Reaction in Tbilisi

Teya Akhvlediani, Georgia’s State Minister for Reconciliation and Civil Equality, commented on September 14 on the decision of the Abkhaz authorities to fully transfer schools to the Russian language of instruction.

“Such illegal actions are a continuation of the policy of ethnic discrimination and Russification carried out by the Russian occupation regime for many years and aimed at destroying the Georgian trace in the occupied territories and the completely assimilating the population”, Akhvlediani said.

According to her, Georgia will spare no effort and will use all the levers at its disposal to provide education in the native language for the population residing in the occupied regions and protect its fundamental rights.

The de facto government of Abkhazia began the process of turning Georgian schools in Gali into Russian in 2015.

In 2020, the Georgian non-governmental organization Institute for the Study of Democracy published a report on the state of the teaching of the Georgian language in the Gali region.

“Georgian as a foreign language is taught only in one school in the city of Gali and in several schools in border villages. As for preschool institutions, preschool education in the native language is completely prohibited in the Gali region”, the report says.

“This process is fully managed by the government of Abkhazia and is part of the policy of Russification of schools with Georgian language of instruction. The declared goal of the Abkhazian authorities is the gradual disappearance of the Georgian language from Gali schools”, the organization said.

If this policy is continued, the last pupils studying in Georgian will graduate in 2022, the report says.

In order to support learning in the native language, in 2019 the government of Georgia made a decision according to which applicants living in the occupied territories will be admitted to higher education institutions of their choice without passing the National Exam.

Each applicant receives the maximum amount of the state grant – 2,250 lari [about $712]. This decision doubled the number of applicants from Gali and Akhalgori in the first year.

Gali district is an administrative unit in Abkhazia. According to the 2011 census, 98.21% of its population is Georgian / Mingrelian.

In 2018, Ketevan Tsikhelashvili, then State Minister of Georgia for Reconciliation, stated that there were 58 schools in the Gali District until 1990s, including 52 Georgian, two Russian, three Georgian-Russian and one Georgian-Abkhazian. The remaining 31 Georgian schools in Gali after the 1992-1993 war gradually switched to Russian-language education. In 2015, the remaining 11 Georgian schools were abolished.

“We still speak Georgian”

Elene (name has been changed) lives in one of the villages of the Gali region (we do not name the village at her request) and is in the eleventh grade of a local school.

After the war in the early 90s, her family first left their home, but then returned.

Elene’s family has a two-story house, the family grows hazelnuts and lives off selling them. Elene tells how ethnic Georgian schoolchildren study in schools in the Gali district.

She agreed to talk to us anonymously, in the presence of her mother.

In the village where Elene lives, the overwhelming majority of the population is Georgian. However, at school, as in all other schools in the Gali district, the main language of instruction is Russian. Children are taught all subjects in Russian – mathematics, biology, history, etc. There is one Georgian language lesson per week in her class and like English, it is taught as a foreign language.

Elene says that the level of teaching in Russian is low, and at home the students speak Georgian or Megrelian, so it is difficult for them to learn in Russian.

“I have to read the same thing several times, sometimes I memorize it – I don’t even understand it. There are many like me”, says Elene.

According to her, some teachers do not know Russian and explain the lesson in Georgian, “but this cannot be said openly”.

At least once a month, a commission comes from Gali or Sukhumi, which also checks the students’ notebooks:

“Georgian inscriptions are not allowed. For example, on the back of the notebooks it says “Iberia” [Georgian manufacturer of notebooks – JAMnews], we are forced to cover up these inscriptions with a proofreader, because our school supervisor makes comments to teachers. The teachers, of course, do not like this, but they have no other choice”.

According to Elene, children outside the school speak Georgian or Megrelian to each other, as do the teachers, since most of the teachers are ethnic Georgians.

“They [the local authorities] are annoyed when we speak Georgian, the Mingrelian language is more tolerated. I, for example, and many others still speak Georgian. We don’t know Russian so what should we do? When we have concerts and performances, we do not speak Georgian loudly at the request of the teachers. They say: “Speak Megrelian at least”.

Elene says that after graduation, most of her classmates will continue their studies at Georgian universities. To do this, they have to prepare with tutors – mainly the Georgian language and the history of Georgia, which is not taught at school.

“My classmates and I are going to study in Tbilisi, because we do not see a future for ourselves in Gali. The maximum we can do is work as teachers. If Georgian is finally removed from school, then there will be no such prospect either. Very few enter ASU [Abkhaz State University – JAMnews]. They hope to find work in their own village or in Gali. But if you want to get a good job here, then you must have someone who will help you – otherwise you will not get along with the Abkhaz. In short, if you want to stay in Abkhazia, then the ASU graduate has more prospects”, explains Elene.

Elene has not yet chosen her future profession, but she sees her future in Tbilisi:

“I have more goals than dreams, now the main thing is to do it. I will be glad to leave for Tbilisi, we are cut off from a lot here, we don’t know much. Having been there, we learn a lot of new things. I’m really looking forward to it”.

“We cry when our children dance, celebrating the victory of the Abkhaz”, Elene’s mother joins in the conversation. She says that even if one of the children in their village decides to continue their education in Sukhumi, their parents will not allow them to do so:

“It will be difficult for our children there, everything can be happen there. As a mother, I will not be able to sleep peacefully at home if my child is in Sukhumi”.

When asked if all young people leave Gali, what fate awaits the region and what are the prospects of Georgians living there, Elene’s mother replies:

“Now it is mostly like that. I have elderly neighbors who have several children, but none of them live at home. They all live in Georgia. Everyone is trying to move to Tbilisi, Zugdidi, Kutaisi and do not want to return, because in fact they did not have a childhood, they lost their childhood and do not want to lose their youth either. They stay where they find a better place, build their nests there”.

“We will probably share this fate – we will grow old here, and our children will be elsewhere. You know, as happens with Georgians, with Mingrels – they do not leave their home, their land, their graves, they somehow try not to. This will probably continue for a long time if we do not return officially and the country is not united. At the moment, I don’t see anything else that would be encouraging. We old people will be left here alone”.

“Of course it hurts. We have a dance studio. When there were concerts and holidays, how many times did we, parents, cry, because Abkhazians of the Victory Day celebrations, and our children dancing. They have to dance in order to keep the right to live there”.

Nana (name has been changed) has been teaching in one of the villages of the Gali region for over 15 years. Several generations of children passed through her hands, and the process of Russification of schools in the Gali district unfolded before her eyes.

Nana says that ten years ago her school was an ordinary Georgian school.

Here, children studied all subjects in Georgian, and Russian was taught as a foreign language.

The situation changed dramatically seven years ago – starting with fourth-graders, children were completely transferred to learning in Russian.

“It was very difficult for the children. They cried bitter tears, because the whole 10th grade studied all subjects in Georgian, and suddenly a biology teacher comes in and explains the lesson in Russian. Few overcame this problem – those who had a Russian grandmother, or one of the parents knew Russian. 2%, not more than that. The rest of the children are still experiencing difficulties. Very talented children are deprived only because they think in Georgian, but they cannot overcome this minimum threshold, called “Russification”.

Nana says that it was difficult not only for the children, but also for the teachers, since the majority do not speak Russian well. They had to undergo retraining during the summer break.

Nana says that the ban on the use of the Georgian language in the educational process is strictly controlled by a special commission. According to her, after switching to Russian, children are far behind in learning:

“A teacher is needed first of all in order to raise a strong and healthy generation, but we cannot do that. We can no longer produce educated and sane generations, because we are shackled hand and foot”.

Supported by Mediaset

Toponyms, terminology, views and opinions expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of JAMnews or any employees thereof. JAMnews reserves the right to delete comments it considers to be offensive, inflammatory, threatening, or otherwise unacceptable