Inside Azerbaijan’s unregulated fertility market

Egg donation in Azerbaijan

While in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) is often seen as a lifeline for couples struggling to conceive, the use of donor eggs in Azerbaijan remains largely unregulated by law.

In some cases, women — often driven by financial need — agree to sell their eggs through unofficial channels, typically via posts on social media. Recently, advertisements have been circulating online, calling on women aged 18 to 30 to become egg donors, promising earnings of “400–800 manats ($235–470) in just 10 days.”

These ads usually state that women who respond will be invited to a clinic for an ultrasound scan. If they meet the requirements, they begin a 10-day course of daily hormone injections. The eggs are then collected from their follicles under short-term anaesthesia. If the woman feels well a few hours after the procedure, she is paid — between 400 and 800 manats, depending on the number of follicles retrieved.

What legal issues do such tempting offers raise? And what risks are egg donors exposed to?

JAMnews looked into the legal and medical sides of this growing practice.

Social media ads and the shadow market

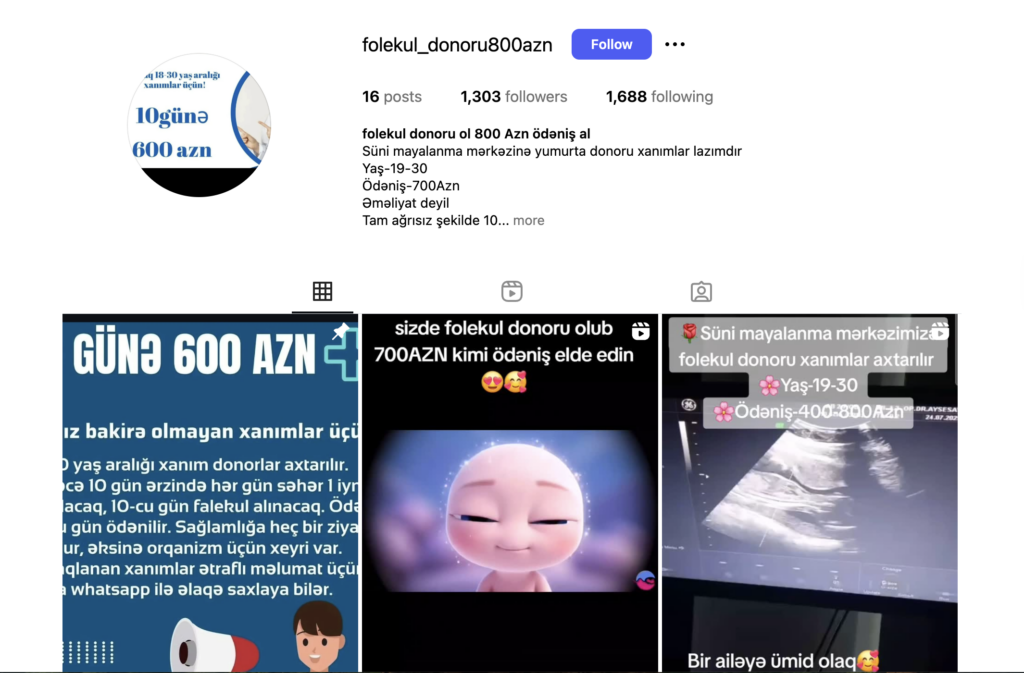

In recent years, ads offering paid egg donation have become widespread on social media and online platforms in Azerbaijan. For example, an Instagram page called folekul_donoru800azn openly invites women to earn 700 manats (around $412) by selling their eggs to unknown recipients.

Many of these ads specify donor requirements: typically young age, good health, and no children. At the same time, the process is often framed as an act of kindness, using hashtags like “let’s give a family hope” or “no family should be left without a child.”

Experts warn, however, that such activity may qualify as a form of human trafficking — and everyone involved bears legal responsibility.

This informal egg donation market is shaped by private clinics and intermediaries. Even well-known doctors and clinics on Instagram post ads inviting women to donate eggs or follicles in exchange for 500–800 manats (about $300–470) within 10 days. Criteria such as age and health are clearly stated.

Couples struggling with infertility often pay close attention to a donor’s appearance, hoping the child will resemble them. Clinic staff aim to match donors with intended parents in order to avoid suspicion about the use of donor material if the child looks noticeably different.

The financial side of this shadow market is also striking. Clinics buy each follicle from a donor for 500–700 manats ($300–410), then offer them to clients undergoing IVF for up to 5,000–6,000 manats ($3,000–3,500). In other words, donors receive a fraction of what clinics and middlemen earn.

According to journalist Lala Mehrali from Səs newspaper, sperm donors are paid just 100 manats (around $60), while egg donors receive 500–800 manats — yet families pay tens of times more for children conceived with this material. On one hand, this system offers financially struggling young people a way to earn money; on the other, it raises serious legal and ethical concerns.

One of the most troubling aspects is the lack of proper information.

Experts say many women don’t realise that children born from their eggs are their biological offspring.

If the same donor material is used multiple times, there’s a real risk of biological siblings growing up unaware of each other’s existence — raising the danger of accidental incest in the future.

Both donors and the wider public remain largely unaware of these risks.

Donor’s experience: “A child was born from my egg, but where and how — I don’t know”

A woman from Azerbaijan who donated her eggs shared her experience with JAMnews. She said she agreed to become a donor because of financial hardship and saw the process as a routine medical procedure. She doesn’t feel ashamed or regretful about selling her eggs.

“It was a necessity. Someone didn’t have a child, they wanted my egg. I said: no problem. There’s nothing shameful in this — not for me, not for their child. It’s just a procedure. The only thing I regret is that it was all unofficial.”

She says the clinic gave her just one document to sign. It stated that she would have no parental rights over the child:

“They gave me a paper, I signed it without reading. They said it was just a formality. The main point was that if a child is born, I could never go to court and say: ‘That’s my child.’”

What bothers her most now is that the entire process wasn’t registered anywhere. In fact, she hadn’t even thought about that — she didn’t know it was something that had to be done officially.

“Now, looking back, I realise a child was born from my egg, but where, to whom, how — I know nothing. I didn’t think it had to be official or legal. I thought things like that only happened in foreign films.”

“I have no idea whether my name, identity, or medical history is saved anywhere. And what if several children are born from my eggs? What could happen in the future?”

This case clearly shows the real risks caused by the lack of legal registration and government oversight. The donor doesn’t feel exploited, but she is increasingly concerned about the possibility of legal and genetic confusion in the future — triggered by things she didn’t know and never thought to ask about.

Legal status: gaps and restrictions in the legislation

In Azerbaijan, this area of reproductive medicine has long remained outside the scope of legal regulation. To this day, the country has not adopted a separate law “On the Protection of Reproductive Health.” The draft law has been under discussion since the 2000s but has been repeatedly postponed due to national mentality and controversial provisions.

In earlier versions of the bill, the practice of donation was allowed under certain conditions (such as being under 35 years old, being healthy, being married, and having at least one child). However, these provisions were later removed from the discussion due to public and religious pressure.

Back in 2015, Musa Guliyev, deputy chair of the parliamentary health committee, stated that since the Caucasus Muslim Board opposes third-party donation in artificial insemination (donor sperm or egg), the issue may be excluded from the bill entirely, with a full ban on donation in Azerbaijan.

In other words, taking religious and ethical values into account, the future law is expected to allow artificial insemination only using the reproductive cells of married couples, without donor material.

Existing legal acts do not directly regulate artificial insemination or the use of donor gametes.

The current law “On the Protection of Public Health” does not include such provisions.

However, the 2020 law “On Donation and Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues” indirectly touches on this area. Article 3.3 of the law states that it does not apply to reproductive purposes or organs, their parts, and tissues used for such purposes (including the use, transplantation, and fertilisation of sperm and eggs).

In other words, the transplantation law explicitly excludes reproductive cells from its scope. This means that as of now, sperm and egg donation for artificial insemination in Azerbaijan is neither officially permitted nor directly prohibited.

As a result, a kind of legal “vacuum” has formed. Due to this vacuum, informal egg donation services have existed for years, and thousands of women have become mothers using eggs from foreign donors.

However, a legal vacuum does not mean that donation is fully legalised. On the contrary, other provisions of existing legislation show that this activity is, in some respects, illegal. For example, Article 32 of the above-mentioned transplantation law prohibits the sale and advertisement of human organs.

According to Article 137 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan, the sale of human organs and tissues is a criminal offence and is punishable by a fine of 6,000 to 9,000 manats (approx. $3,500–5,300), correctional labour for up to 2 years, or imprisonment for up to 3 years.

Even conducting organ transplants through intermediaries or in medical institutions without permission carries separate criminal liability.

According to legal experts, the sale of eggs may also be considered organ trafficking. The principles of national legislation do not allow the transfer of human body parts in exchange for payment.

Therefore, posts on social media such as “looking for donor, will pay” violate the advertising law and are prohibited.

On the other hand, Azerbaijan’s Family Code defines certain legal frameworks related to artificial insemination and surrogacy. According to Article 46, married couples may, by written consent, resort to artificial insemination or embryo implantation and are recognised as the legal parents of the child born through this method.

Article 46.4 is particularly important. It states that if a child is born as a result of artificial insemination carried out with the written consent of a married couple, they may be registered as the child’s parents in the birth certificate — with the consent of the woman who gave birth (i.e. the surrogate mother).

In other words, the law recognises surrogacy and, with the surrogate’s consent, allows the biological parents to establish their parental rights over the child.

According to Article 47.3, a spouse who has given official consent to artificial insemination cannot later use this fact to dispute paternity.

In other words, if a man gives official consent for artificial insemination using donor material for his wife, he loses the right to deny paternity later based on lack of biological relation.

These provisions show that in the area of family law, the status of children born through donation and the issue of parenthood are regulated. However, due to the lack of concrete mechanisms regarding how donor material is obtained, how donors are selected, their rights, and payment, a legal vacuum arises in practice.

Despite the legal uncertainty, in recent times the authorities have begun to take action in response to such cases. For example, the Ministry of Internal Affairs has stated that investigations have begun into social media ads offering paid donation.

At the same time, in 2024, representatives of the Ministry of Health announced that the final draft of the “Reproductive Health” bill is ready, and that a legal framework is needed for socially sensitive issues such as artificial insemination, sperm/egg donation, and surrogacy.

According to deputy minister Nadir Zeynalov, society was not previously ready to accept such innovations, but a shift in public thinking has created the need to pass this law.

The bill is expected to be submitted to the Milli Majlis (parliament) for discussion and approval in the near future.

If passed, this will be the first law in Azerbaijan to comprehensively regulate the field of reproductive technologies.

Rights and health risks for egg donors

Under the current legal framework, the specific status and rights of women who become egg donors are not officially recognised. According to the law, the mother is defined as the woman who gives birth to the child, regardless of biological origin.

This means an egg donor has no legal parental rights over a child born from her egg: she cannot claim custody and bears no legal responsibility for the child.

In practice, where anonymity is maintained (and in Azerbaijan, donors are typically anonymous and unregistered), the donor’s identity remains hidden, and the child has no way of finding them in the future.

However, this does not mean the donor has no rights at all. Before the medical procedure, donors also sign certain contracts and consent forms.

Still, the protection of the donor’s rights in these agreements is weak, as the procedure itself takes place outside official regulation. If any problems arise, the donor would face difficulties seeking legal protection.

For example, if her health is harmed or the promised payment is not made, it would be difficult to pursue justice through the courts, as the donor has formally taken part in an illegal transaction.

One of the most important concerns for female donors is the health risk. Egg retrieval is a serious medical intervention. Gynaecologists warn that the number of eggs in a woman’s body is limited, and repeated ovarian stimulation and follicle extraction can harm a woman’s reproductive health.

According to gynaecologist Laman Aliyeva, repeated donations may lead to irreversible damage to ovarian function and the loss of the ability to conceive in the future.

The procedure itself also comes with risks. First, stimulating a large number of eggs using hormones can lead to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

This condition may cause fluid buildup in the abdomen, blood clots, kidney and liver failure — and in rare cases, even death.

During the second stage, when follicles are extracted with a needle (a procedure done under ultrasound guidance and short-term anaesthesia), there is a risk of damage to internal organs or blood vessels, internal bleeding, and infection.

In rare cases, such complications may be life-threatening. In effect, the donor is putting her health at risk, and the 500–800 manats she receives is presented as “compensation” for those risks.

However, in some cases, donors are not fully informed of the risks — and may even be deceived.

In many cases, women are told that only one follicle will be retrieved, but under anaesthesia, 3 to 6 follicles are actually taken.

Thus, a woman receives 500–700 manats as “payment” for one egg, while in reality several valuable eggs are taken without her knowledge.

Each additional egg may be given to another patient and brings additional profit to the clinic. As a result, in just 10 days, one woman may “genetically give life” to 2–5 children — though they are carried by other women (as in the case of surrogacy).

This situation clearly involves high risks — both medical and ethical. A woman donor may suffer irreversible physical harm and loses her genetic children permanently — for a modest fee.

In the future, she may face psychological trauma — both from health complications and from never knowing the fate of the children born from her eggs.

Health professionals stress the need for strict oversight in this field.

It is proposed that once a reproductive health law is passed, a central donor registry should be created. This would store state-monitored information about each donor — age, health status, number of donations, etc.

Such a registry would help prevent multiple donations by the same person and reduce the risk of genetic relationships between future spouses.

The law should also clearly require donors to undergo medical and psychological evaluations, ensure voluntariness and no-payment principles, and maintain anonymity and confidentiality.

Clear regulations are also needed to define the rights and responsibilities of both donors and recipients (those who use donor material).

Only under such conditions can women be protected from exploitation and deception — and the procedure itself conducted in line with medical standards.

The regional and global context compared to Azerbaijan

Attitudes toward egg and sperm donation vary widely across the world. Some countries have legalised and strictly regulate this area, while others ban it due to religious or ethical reasons. Azerbaijan’s neighbours also take differing approaches.

In Turkiye, the use of donor gametes in artificial insemination is prohibited by law.

According to national legislation, IVF (in vitro fertilisation) can only be performed using the couple’s own reproductive cells, and only if they are legally married. Egg and sperm donation, as well as surrogacy, are not allowed for religious and ethical reasons.

As a result, couples who want children but cannot use their own reproductive cells for medical reasons are forced to seek treatment abroad — for example, in Cyprus, Georgia, or other countries where donor procedures are more accessible.

Iran and many other Muslim-majority countries follow similar restrictions. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, only embryo donation has been officially legalised (a specific law was passed in 2003), while sperm and egg donation are not explicitly addressed in the legislation.

These issues are mostly governed by religious fatwas. According to local media, in Iran and some other Islamic countries, the use of donor material from unrelated individuals is considered “unacceptable.”

There are also significant ethical debates on this topic within Iranian society, and the practice of donation remains rare.

The situation in countries across the region

In Armenia, Georgia, and Russia, reproductive donation is legal, and internationally recognised clinics have developed in these countries.

Since 1997, Georgia has adopted laws permitting surrogacy and the use of donor sperm and eggs. IVF clinics in the country serve both local and international patients.

According to Georgian law, the legal parents of the child are the couple who commissioned the birth, and the donor or surrogate mother has no parental rights.

There is ongoing discussion in Georgia about placing restrictions on this sector, particularly for foreign citizens. However, the field remains relatively open and attractive for visitors from abroad.

Armenia is also among the countries with liberal legislation in this area. Both commercial and altruistic (unpaid) surrogacy are allowed, egg donation is legal, and the country is becoming a destination for reproductive tourism, including for foreign nationals.

For instance, under Armenian law, a child born from a donor egg is automatically registered under the names of the intended parents — this is considered valid consent by the surrogate mother.

This clear legal framework simplifies the process for international couples seeking reproductive services.

In the Russian Federation, reproductive technologies are also regulated by law, and egg and sperm donation are legal medical services.

Russia has some of the most liberal legislation in this field among European countries. The state ensures donor anonymity, and clinics are allowed to recruit donors and provide official compensation.

According to guidelines from the Russian Ministry of Health, egg donors must be women aged 20 to 35, healthy, and with at least one healthy biological child.

The personal data of donors and recipients is protected as medical confidentiality.

If a child is born via IVF with the consent of a legally married couple, they are listed as the parents on the birth certificate.

Legally, this means the child born in Russia has no connection to the donor. In general, Russian legislation is more permissive compared to most European countries.

For example, while anonymous and paid donation is banned in several Western countries, it is legal in Russia. As a result, cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg have become well-known IVF hubs attracting international patients.

The situation in Western countries varies

The United States has one of the most developed egg donation markets. Commercial donation is fully legal, and donors can receive tens of thousands of dollars depending on their profile, education, and appearance.

In the European Union, regulations are generally stricter. In Germany and Switzerland, for example, egg donation is completely banned (IVF is only allowed using a couple’s own cells, in accordance with embryo protection laws).

In countries like the United Kingdom and Canada, donation is only permitted on an altruistic basis — meaning only expenses are compensated, with no profit involved. Some countries have abolished donor anonymity, granting children born via donation the right to learn the donor’s identity upon turning 18. In the UK, for example, donor anonymity was partially lifted in 2005.

Spain, Greece, and Ukraine are countries where both anonymous and compensated donation are allowed, and specialised clinics operate there.

Ukraine and Georgia, in particular, were previously popular destinations for foreign couples seeking surrogacy and egg donation. However, following the war in Ukraine, Georgia and Armenia have partially taken its place.

Thus, Azerbaijan’s position falls somewhere between Turkiye and certain Muslim-majority countries — that is, among states where donation is either effectively banned or at least not legalised.

At the same time, a kind of “shadow market” has developed in Azerbaijan due to the legal vacuum.

In this context, Azerbaijan essentially has two paths: either follow the model of Turkiye and many Islamic countries by fully banning donation and eliminating existing unofficial practices through strict sanctions; or, like Georgia and Russia, create a clear legal framework addressing donor registration, selection, medical oversight, and the legal status of the child.

According to lawyer Ramil Suleymanov, if Azerbaijan chooses to legalise this activity, it will require not only the adoption of a specific law but also amendments to the Family Code, the Civil Code, and the broader legal system.

This is because the institution of donation touches on many areas — from the concept of parenthood to inheritance systems and health insurance.

He believes that unless the state starts implementing strict punitive policies under the current conditions, society may face unpredictable consequences in the future: marriages between relatives, health problems for donors, legal disputes, and so on.

Conclusion

The situation in Azerbaijan regarding in vitro fertilisation and egg donation remains extremely complex.

On one side are thousands of families longing for a child and relying on donor reproductive cells.

On the other are young women, facing financial hardship, who agree to “sell” their genetic material — and risk their health in the process.

Current legislation neither fully rejects this reality nor fully accepts it.

As a result, the rights and interests of both intended parents and donors remain insufficiently protected.

Passing the long-discussed law “On Reproductive Health” could be a crucial step toward eliminating the legal vacuum. The law must clearly define all issues that are sensitive within society, including:

- whether donor sperm and eggs are allowed;

- if so, under what conditions (such as maximum donor age, anonymity, and limits on repeated use);

- the legal status of surrogacy;

- and state support for families facing infertility (for example, IVF coverage through health insurance).

In the meantime, at the very least, public authorities must engage in awareness campaigns and warn young women about the risks behind tempting offers seen on social media.

Until a legal framework is put in place, egg donation in Azerbaijan will remain a legal “grey area” — an activity that is neither explicitly banned nor officially allowed. This means that both medical-ethical and criminal-legal problems are inevitable.

The risk of marriages between genetic relatives, the lack of a genetic data registry, and the exploitation of donors all pose serious threats to society.

Lawyer Tural Huseynov emphasises that current legislation does not allow any payments in exchange for donation, and the sale of human organs is prohibited in all cases.

This means that paid egg donation may also be considered illegal and unacceptable.

As a result, law enforcement may begin tightening measures against such cases. But in practice, proving violations is difficult — and social demand persists. For this reason, the only lasting solution is to establish a modern legal framework and introduce proper state oversight.

News in Azerbaijan