How the game of war is played in Armenia and Azerbaijan

In the South Caucasus, new technologies and virtual reality are not being used to help to spread human values and peacebuilding; instead military games are developed which reflect the societies’ attitudes towards the unresolved conflicts.

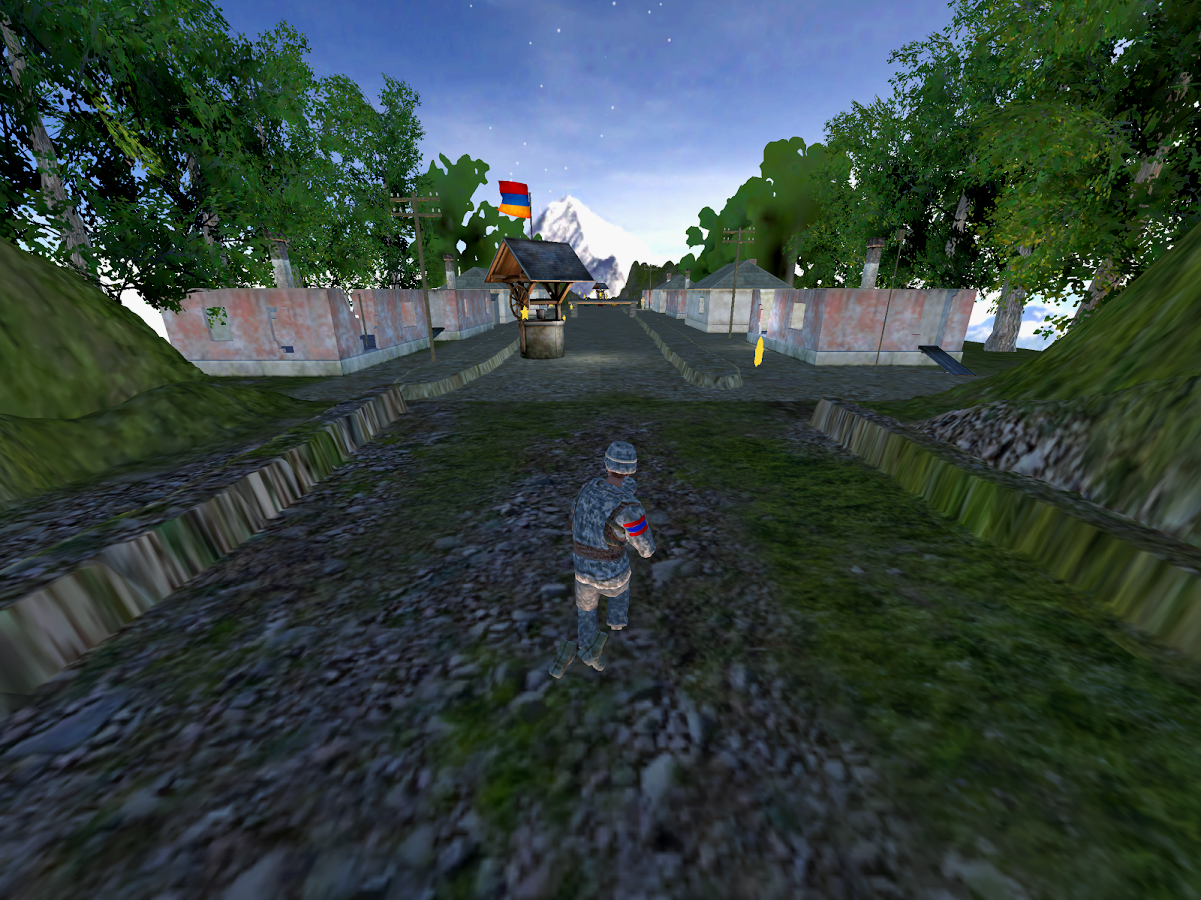

Thirty-two-year-old IT expert Karen Sogoyan, who developed the game Hi Zinvor (Armenian Soldier), says it was not created to sow hate among users. The military shooter game, he claims, merely aimed to pay tribute to Armenian soldiers. Nevertheless, a number of elements in the game suggest that its hero is battling

The game opens with a parachute jump from a helicopter to the sounds of the song ‘We Are Going to War, Me and My Brother’. After landing on the ground, the soldier opens fire on enemy troops who are hiding to either side of him. Killing some of them, the main character then runs off, continuing to destroy enemy tanks and aircraft along the way.

We Are Going to War, Me and My Brother

The armed clashes that broke out on the night of 1 April 2016 and lasted for four days became the most serious since the end of the war in Nagorny Karabakh (1991 – 1994) and the 1994 ceasefire between Azerbaijan, Armenia and Nagorny Karabakh. In Armenia, these events, which took hundreds of lives in total, became known as the four-day April war. In Azerbaijan, they are referred to as the April clashes.

During the April war and in the days that followed, the image of the heroic soldier took centre stage in Armenia and Nagorny Karabakh. It was within this context that Hi Zinvor, the first online game for mobile phones, was developed. Released in February 2017, the game now boasts more than 70,000 users in Armenia and across the world.

The shooter game does not contain any bloody or cruel scenes. It boasts twelve locations including towns, military bases, forests, mountains and fields created using computer graphics and design,. It does not include a single real place name associated with Nagorny Karabakh, yet clearly deals with the unresolved Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict.

‘After the April war, I was determined to create a game that would, as far as possible, reflect the elements of Armenian reality. In those days, the Armenian soldier played a crucial role in the life of our nation. Even today, he remains our finest hero,’ Karen Sogoyan explains

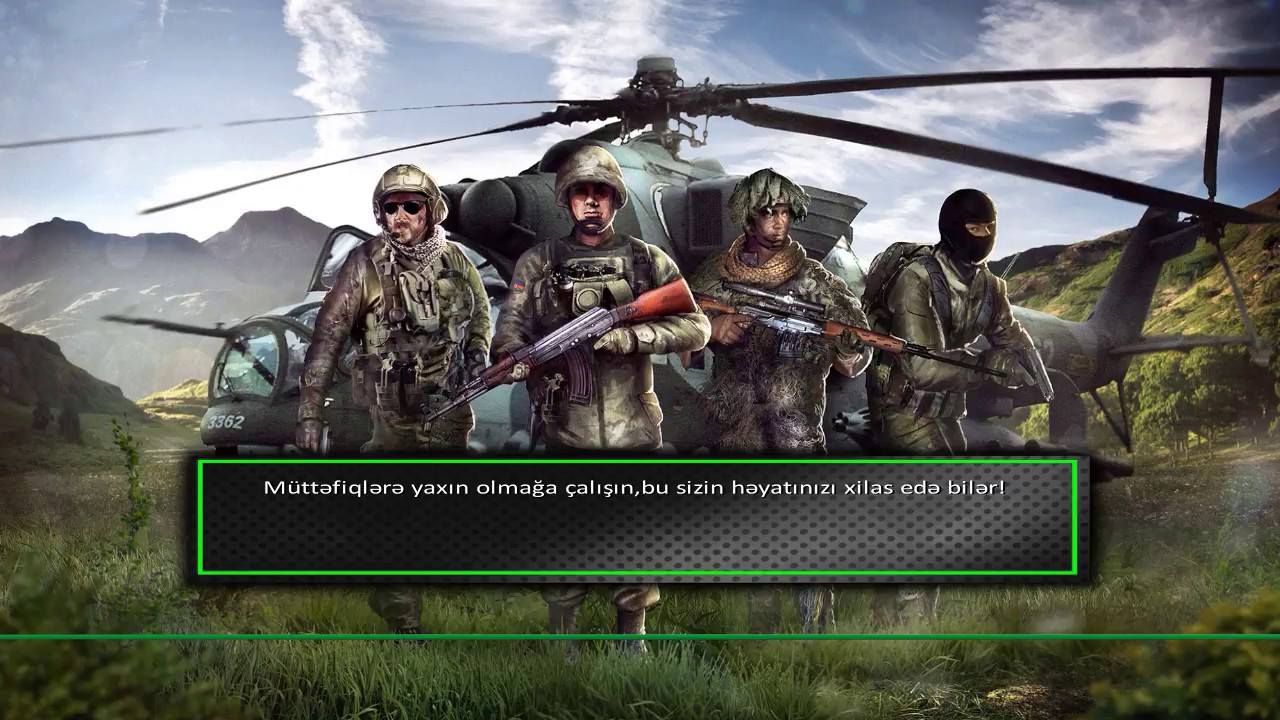

Azerbaijan also has its own range of computer games aimed at ‘raising the fighting spirit’, expressly supported financially by the country’s Ministry for Youth and Sport. Game creator Farid Khagverdiyev says he was driven by patriotic motives: Azerbaijan did not have its own computer games, and he felt this should be rectified. The conflict in Nagorny Karabakh, he decided, was the obvious theme for a shooter game.

Today, Khagverdiyev is Head Programmer with a company called AzDimension, but back in 2006, when he started developing these games, he was still at school. His first two games were released without any state sponsorship, purely out of enthusiasm.

‘Of course, the first game, which was called Karabakh War, was rather primitive: I barely had any experience, back then. But many people seemed to like it, so I decided to carry on.’

In 2012, an improved version appeared, which was named İşğalAltinda: Şuşa (Under Occupation: Shusha).

In this game, the action takes place in the future, during a second war in Nagorny Karabakh. In one of the battles, the main character’s unit gets caught in an ambush. All the soldiers are killed, apart from the main character and his commanding officer. At the other end of the village, though, friendly troops await. The aim of the game is to reach them.

The next game, İşğalaltında: Aqdam (Under Occupation: Agdam) was released with the aid of state sponsorship.

The action takes place at two different times: in the 1990s, during the battles for Agdam, and in the future, during its retaking. The user plays the part of several soldiers from a special forces unit.

Having had access to archive photographs, the programmers were able to reproduce the appearance of Agdam with the utmost precision. Many gamers, indeed, choose this game precisely because it gives them an opportunity to ‘visit’ Nagorny Karabakh, which they are too young to have done in reality. The town is shown at two different times, before and after the outbreak of war. The weapons in the game are also perfectly ‘real’: the Zəfər pistol, İstiqlal sniper rifle and military hardware used by Azerbaijan.

Currently, the İşğalaltında series has more than 100,000 users. Most of them live in Azerbaijan, although there are also Azerbaijanis living in Russia, Turkey and Iran who play it.

The final game of the series, İşğalAltında: Qisas (Under Siege: Revenge) appeared last summer, featuring a number of changes, improved graphics and encyclopaedic inserts with information on the main places of interest in Shusha.

Conflict studies expert Artak Ayuntz is convinced that Hi Zinvor reflects a growing militaristic mood in Armenian society.

‘The game ties in with the logic of the nation-army concept. All soldiers have to be prepared to give their lives, should war break out once again. Young Armenians who play this game most likely see Azerbaijanis as their enemies: the colours of the enemy flag in the game are like those of the flag of Azerbaijan, although this is not immediately obvious. Having said that, portraying the enemy as a ram in order to humiliate Azerbaijanis is nothing new in the Armenian online space,’ the conflict studies expert says. Such games, he is convinced, have a negative effect on users.

According to Ayuntz, military shooter games encourage hate among young people, stimulating the urge to resolve conflict through the use of weapons and force.

Every day, more than 3,000 users play Hi Zinvor. These are mainly men of different ages. Some users are children. The most active age group is 18 to 34.

‘The fact that the game encourages a sense of satisfaction at killing someone, and that this makes the player feel like a hero, is extremely dangerous,’ says Gulnara Shainyan. The founder of the non-profit organisation Democracy Today, she stresses the need to create more peaceful games in Armenia.

Hi Zinvor, she says, is geared to foment hatred and enmity.

Azerbaijani psychologist and psychiatrist Elchin Dzhabrailbekov does not feel that computer games, even those connected with the Nagorny Karabakh conflict, should be taken this seriously. And he certainly does not believe that such games are capable of raising the patriotic spirit.

‘Patriotic spirit is what makes you leap up from the couch and actually do something, whereas video games are what keep you on that couch. At the end of the day, that game is probably no worse than those ‘tank’ games that everyone is so fond of. Maybe it’s actually better. Perhaps some people are able to sublimate their militaristic tendencies that way.’

Dzhabrailbekov does not see using the Nagorny Karabakh conflict as the theme for a video game as unethical. A great many games, he notes, are based on historical themes.

At the end of the day, Dzhabrailbekov feels, video games about Nagorny Karabakh are neither dangerous, nor useful. They should, he says, be seen merely as a pleasant pastime for those interested in such things.

There are no games about the conflict in Armenia or in Azerbaijan that advocate a humanistic, peaceful approach.

Many international organisations, however, are continuing to develop a range of games that stress the importance of humanism and peacebuilding in the context of other conflicts.

Focusing on cooperation and communication in the digital world, these peacebuilding games stress the need for dialogue whilst attempting to break down negative stereotypes.

A competition organized by the United Nations Development Programme in 2014 saw the creation of an entire series of such games. Arousing little interest, they remained unpopular.

Information security expert Samvel Martirosyan warns that military games can have a serious psychological impact on how the youth of today view the world.

‘Psychologists and teachers are alarmed: most games are very aggressive, they stimulate negative emotions and behaviour. In the gaming industry, humanism is not especially widespread,’ Martirosyan notes.

Father of a fifth-grader Vagif Abasov is a secondary school history teacher. He says he would never allow his son to play this, or any other computer game that deals with a specific war and real nations destroying each other.

Such, for instance, are the highly popular games about World War Two, Abasov says. Several of these, incidentally, allow the gamer to play on the side of the Nazis. All military games, and especially those in which the enemy’s nationality is made clear, Vagif Abasov says, promote increased aggression among young people and strengthen the enemy image.

‘These kinds of games are really only useful to students of military academies if they allow them to work on their tactics and strategy, fighting an enemy in a wooded setting, for instance. But even in this case, it is better to name the enemy simply ‘X’,’ Abasov suggests.

There are, however, some exceptions, such as the computer game This War of Mine, developed by 11 Bit Studios. So popular it gained international acclaim, it features peaceful civilians trying to survive in a town under siege. Struggling with the lack of supplies and medicine, they are in constant danger from snipers as they are forced to make difficult decisions that will impact their lives or may result in death. In creating this game, which today boasts hundreds of thousands of users, its Polish developers strove to show the true face of war, the calamities and destruction it brings, and its impact on society and on individual people.

Developing projects such as this requires funds, and the gaming industry is seldom interested in funding peaceful games.

‘The prevailing discourse in Armenian schools and everywhere else today is nationalistic and militaristic, that much is clear, and the state does everything it can to support and encourage this. Developing and marketing a game that encourages peacebuilding in this kind of atmosphere is a very difficult task. How does one get adults and children interested in it? How does one get a proper following for it, not just 10 people from NGOs? This is most likely why such games are simply not made here in Armenia,’ suggests Isabella Sargsyan, Program Director at the Eurasia Partnership Foundation.

The region, Sargsyan stresses, is in dire need of any peacebuilding initiatives. Which instruments are more effective, the online space or face-to-face meetings, however, is another matter.

‘From the point of view of peacebuilding and conflict transformation, there is probably no instrument more powerful than face-to-face meetings. You can advocate whatever you like with the aid of a game for as long as you want, but until you come face to face with a real person and undergo that process of transformation, the efficiency is going to be a lot lower,’ Sargsyan concludes.