Survivors of Armenia’s 1988 earthquake tell their stories 33 years later

Exactly 33 years ago – at 11:41 am on December 7, 1988 – a terrible category 9 earthquake on the Richter scale shook Armenia. 25,000 people died, of which 15-17,000 were killed in Gyumri, and 4,000 in Spitak.

11 cities and 342 villages were affected. 514,000 people were left homeless.

The stories of three people who survived this disaster and rebuilt their lives

The director

Thirty years later, director Arusyak Simonyan achieved her goal of making a film about the destructive earthquake that took place in Armenia. The film My New Year tells the story of a family from Spitak which was at the epicentre of the 7 December earthquake.

Arusyak condensed her and her family’s emotional experiences into a 27-minute film. It was awarded a prize for the best short film at the Pomegranate international film festival, which is held each year in Toronto.

“From the moment I enrolled in theatre school, my friends already knew that I was going to shoot a film about the earthquake. Perhaps this was an attempt to save my soul via my profession, through art. I dedicated this film to all the survivors who lived through the chaos and could somehow live on,” says Arusyak.

Although Arusjak remembers what had happened, the full comprehension of it came later. She says that she and her brother only came to understand years later that, in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, the children who were carried out of the kindergarten building and laid on the ground next to them weren’t sleeping. Of their childhood friends, only seven were saved.

“My mother died during the earthquake, and they couldn’t find her. My father dug 300 graves for his countrymen. They managed to find mother only four months later. He did an important thing for me: I now know where my mother is buried. I am eternally grateful to him. Four months going through dead bodies: what sort of willpower was necessary to go to such lengths?” says Arusyak.

In the film she tells how people overcame their pain, and what motivated her father to overcome his own. Once he returned home to find his six year-old daughter and four year-old son playing “earthquake”:

“At that time we lived in a makeshift trailer home; we set up our dolls and then hit them with something – they all fell over and we began to yell, to save the dolls and ‘bury’ them. It was this bit that made him emotional. He didn’t want for our childhood to be irrevocably lost to us. Father went somewhere and came back with a big Christmas tree, even cleaned some things out of our place so that it would fit. We had the most enjoyable New Year’s celebration.

“There’s one part in the film about how a person heals themselves, their soul, and begins to live for their children. This is the strength of our people, it’s thanks to this that we still exist. There is one more interesting moment: at the time of filming, I was expecting my third child. I didn’t plan to film my children, but then we decided that the role of the young girl would be played by my eldest daughter. I gave her my mother’s name.”

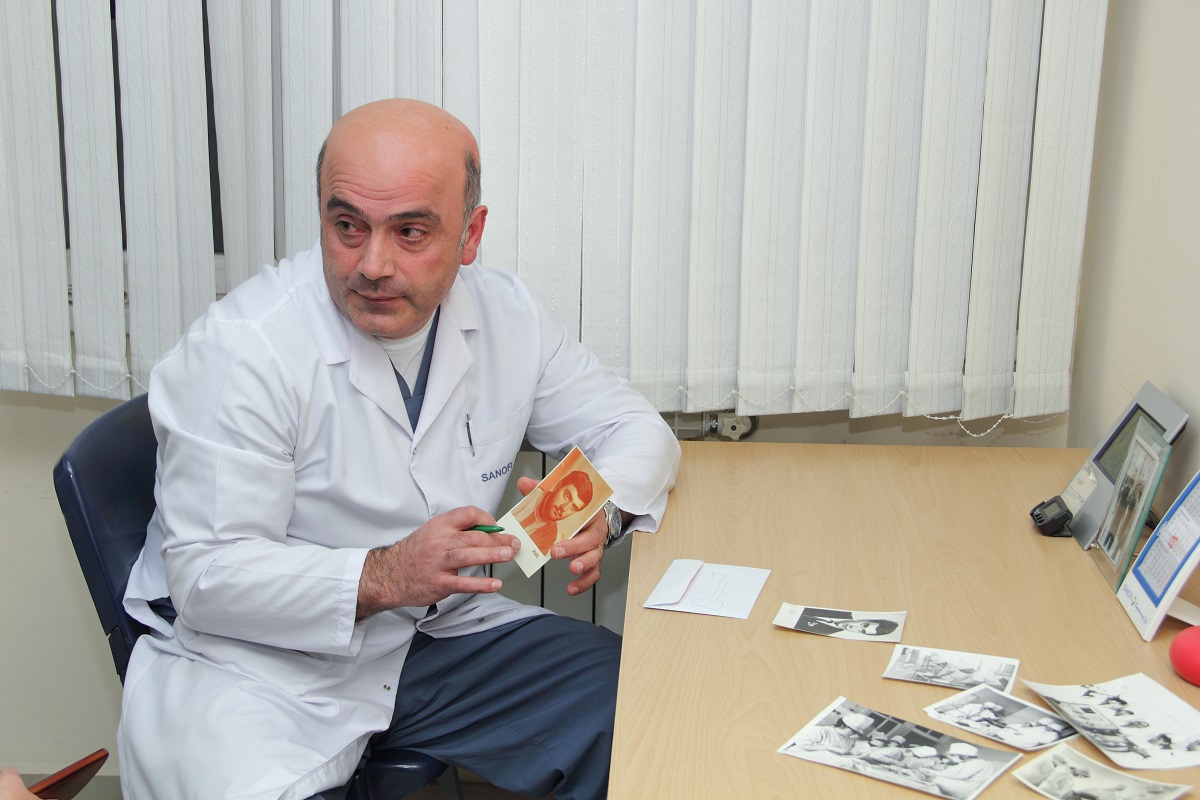

The doctor

“Later I got married, and my spouse and I had children. Afterwards we fought to become normal people again and wanted to somehow help our city,” says Vardan Sukiasyan, doctor at the Gyumri medical centre.

He remembers that on 7 December 1988 at the time of the earthquake, he was at high school in his mathematics lessons.

“The school building partially collapsed. Like many other students, I jumped from the second-story window. I broke something, but while in shock I ran to search for my loved ones,” says Vardan.

After finding his mother and sister, the 16 year-old ran onwards in search of his father, a famous surgeon in the city. On the way to the hospital he noticed that the whole city was in ruins, and saw people running in various directions, in panic, and he saw the dead.

“At the time of the earthquake my father was performing an operation. He tried to carry a patient out of the hospital in his arms, but the staircase in the building completely collapsed on top of him. It was there that we found him,” says Vardan, looking away.

It was then that he swore to his father that he would carry on his work:

“I made a decision when we pulled my father from the ruins. I swore that I would become a doctor no matter what. At the time, they set aside additional places for people with disabilities at the Yerevan medical university, so that, after placement interviews, they could attend university and, after graduating, return to their home regions and work in poverty zones. As a result of the injuries I sustained during the earthquake, I was classified as having a second-degree disability.

“I now live on principle, to bear my father’s name with dignity. What I was unable to do for my father, I do for my patients. My heart is not so heavy when I help others. My mother was my life coach. She always said: ‘Son, you must live, and thanks to you Gyumri will live; become a good specialist and help your city get back on its feet’. Thirty years have passed, but there are still so many wounds, so many problems. The most important thing is that now there are a few more smiles in the city.”

The rescue worker

Levon Bozoyan, a well-known rescue worker in Gyumri, was 16 years old in 1988. Remembering the day of the earthquake is still difficult for him. He and his classmates were unable to flee the school, and the building collapsed in seconds. Levon and his friends were pulled from beneath the rubble by the parents of other students using makeshift tools such as saws and hammers, whatever was at hand.

“My legs were trapped in the banister, and a metal fitting pierced my face on the right side. I don’t want to think about it. In our class there were 24 students – 12 perished. We were all together, laying on top of one another.

“This was a natural disaster, so there was nothing we could have done. But even now, when my classmates and I get together, we always remember that day. And we begin to feel guilty, that we’re here, and they’re not. It’s probably this feeling of guilt that made us form the emergency help squadron.

“If we’d had a professional rescue service then, like we do now, there would have been more survivors. Soldiers came to the disaster area to help as did members of the civil defense units, but not rescue workers. The first rescue squad in Armenia was formed by Germans in Spitak. We got friends together and, using public funds, created our squadron in Gyumri. Among us were mountain climbers and guys working at the local airport.

“When you rescue someone, you have a very particular feeling, your soul becomes lighter when you manage to help. We stayed in our town, Gyumri, to live and overcome, to save ourselves and make our city live,” says Levon.