How the Georgian Judicial System Fell Under Western Sanctions

Georgian judicial system

Georgia is awaiting the decision of the European Union on granting it the status of a candidate country. And one of the 12 recommendations toward that end is to conduct effective judicial reform.

But experts fear that the authorities will not give up their influence on the system, as parliamentary elections will be held in the country in 2024 in which the Georgian Dream party will try to stay in power for a fourth term. Without a loyal court, it will be difficult for it to do this, observers say.

During Georgia’s 32 years of independence the country has achieved many successes, but an independent court is not one of them. All international reports say that the judiciary in Georgia is an instrument of political influence and hinders the country’s aspiration to enter the Euro-Atlantic space.

On April 5, the US State Department imposed sanctions on four Georgian judges and their families. Corruption and abuse of power were cited as the reasons.

Opponents of the authorities call these judges members of a judicial clan working on orders from Georgian Dream.

This is the first time that the United States has imposed a sanctions on citizens of Georgia, and it is no coincidence that the first sanctions fell on judges, experts say.

Who was sanctioned?

The US sanctions affected three current, life-term judges and one former judge. They and their family members were banned from entering the United States.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a statement that “these individuals have abused their positions as chairmen of courts and members of the High Council of Justice, thereby damaging the rule of law and public confidence in the court system in Georgia.”

NGOs call them members of an influential judicial clan, closely associated with the Georgian Dream and personally with Ivanishvili. This clan controls the judiciary and has the leverage to appoint, promote and punish judges.

The sanctioned judges began their careers during the National Movement’s rule. Their names are closely connected with the scandalous affairs of that time.

Levan Murusidze is a lifelong judge of the Court of Appeal and a member of the High Council of Justice, which decides on the appointment of judges in the Georgian judiciary.

Murusidze has been a Supreme Court judge since 2006, during Saakashvili’s presidency. Even then, the activities of Murusidze were criticized. It was he who in 2007 commuted the sentence of those accused of the murder of Sandro Girgvliani. His name is associated with other high-profile cases that remain a black mark on Saakashvili’s rule, most of which Georgia later lost in the European Court of Human Rights.

However, after the change of power, Murusidze was not removed from the system, but was on the contrary promoted.

Ivanishvili personally met and lobbied for Murusidze’s advancement and called him a “victim of the system”:

“I cannot hide my emotions and I am convinced that there are people in the court, and here I saw a person who really takes responsibility for ensuring that the court in the future is fair and has authority and trust among the population,” Ivanishvili said about Levan Murusidze in October 2016.

Later, in 2019, Georgian Dream chairman Irakli Kobakhidze explained the resurgence of discredited judges this way: “People who committed bad deeds en masse under the previous government are now doing good deeds.”

Murusidze is a millionaire. Georgian investigative journalists found out that he has undeclared property registered in the name of his common-law wife. Commenting on the sanctions, he said: “It’s nothing if they don’t let us into the US or the EU now. So my grandfather did not go there and lived like a human.”

The sanctions also included Mikhail Chinchaladze, chairman of the Tbilisi Court of Appeal. NGOs call him the leader of the judicial clan. In 2005, he received the Order of Honor from Saakashvili. Chinchaladze is also a millionaire and hides his property in the declaration, registering it under his aunt and mother.

Another sanctioned judge, Irakli Shengelia, Chinchaladze’s deputy and his closest aide, has close ties to the Georgian Dream party. Commenting on the sanctions, he said that he had nothing to do in the United States, where “the ability to change the sex of a six-year-old child” is considered the main democratic achievement. “I have nothing to do there, since such “values” have nothing to do with my family,” he said.

Valerian Tsertsvadze, a sanctioned former judge who left the system six years ago after being accused of lobbying his company in a lawsuit. His daughter is a US citizen since she was born there in 2013.

Information about the judicial clan has been collected for years. There are many witnesses and testimonies about what this clan was doing.

The era of the “United National Movement” – Saakashvili’s mistakes

The experts with whom JAMnews spoke unanimously assert that despite the fact that every political force that came to power declared the need to reform the judicial system, none of them could free it from its own influence.

“The main problem is that there is no political will for this,” says Nazi Janezashvili, director of the Judicial Watch organization, which has been studying the Georgian judicial system for many years.

Mikheil Saakashvili promised the independence of the judiciary. He carried out a number of drastic measures, including mass dismissals of judges and their replacement with new cadres.

As Giorgi Mshvenieradze, head of the Guardians of Democracy organization, says, this approach turned out to be a mistake:

“When you use force to punish judges, including procedures that do not meet legal criteria, it can cause fear among newly appointed judges. That is exactly what happened, and the idea of an independent judiciary was undermined from the very beginning.”

Grassroots corruption had been eradicated, but the courts remained under political influence.

The judicial system under Saakashvili was characterized by a strong accusatory bias. Those accused of a criminal offense in a Georgian court had very little chance of being acquitted. For example, in 2010 the Tbilisi City Court heard 7,296 criminal cases, and only in 21 cases (0.04 percent) were the defendants acquitted.

The era of “Georgian Dreams”: the judicial clan

Many hoped that the situation would change in 2012 when the Georgian Dream party came to power, since one of the main promises of this party was an independent and fair judiciary.

However, after eleven years the Georgian judicial system faces even greater problems, experts say.

Not only did Georgian Dream not get rid of judges who followed political instructions under the previous government, but on the contrary promoted them in the judicial system:

“[The government] tested the judges for loyalty and then appointed them to positions for life, while appointing judges with the worst reputation to senior positions in the judiciary,” Giorgi Mshvenieradze says.

Experts believe that Georgian Dream has developed a new model of court management – it has created a kind of “clan” within the judiciary that controls the system.

“While under the previous government, the Minister of Justice could call a specific judge, today the system is more centralized – a member of the government does not need to individually call a single judge, the system is controlled by a clan that decides everything,” Nazi Janezashvili, a critic of the judiciary, says.

Observers believe that Bidzina Ivanishvili was personally involved in this process. This is also indicated by his meetings with Murusidze.

When asked in which cases Georgian Dream has shown interest, experts list such cases as Rustavi-2, Cables, Iveri Melashvili, and Nika Gvaramia.

“Take the case of Nika Gvaramia. This is an open and clear example of how a person can be imprisoned on a trumped-up charge,” Giorgi Mshvenieradze says.

Gvaramia is the director of the opposition TV channel Mtavari Arkhi. One of the episodes in his case was the use of an official car for personal purposes — he drove his children to school.

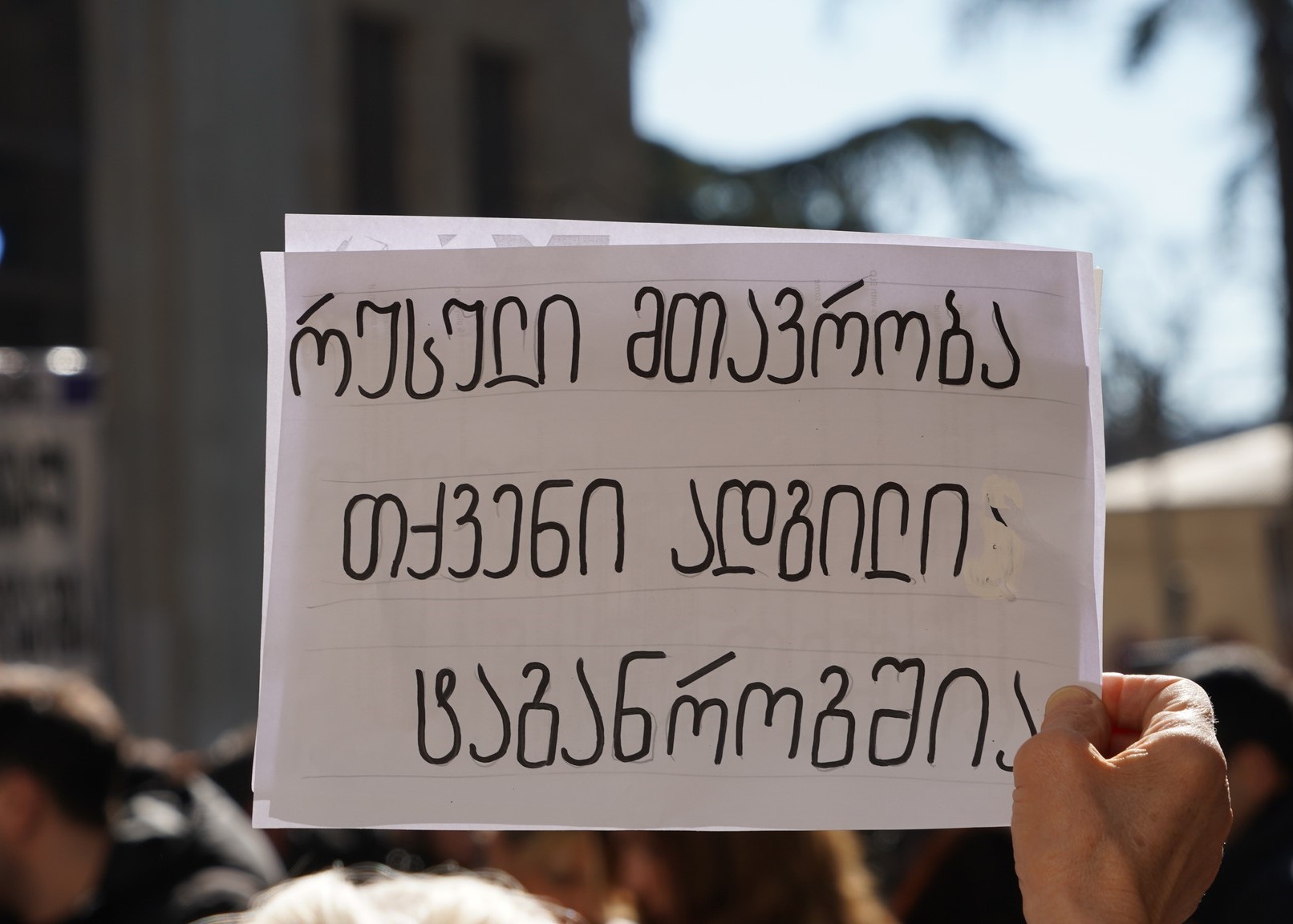

Experts also draw attention to cases of detention of civil activists at peaceful demonstrations and their trials. Many are subject to heavy fines and administrative penalties.

“Such cases always show the tendencies and attitude of the government. All court decisions are similar in such cases, which is questionable. It is impossible for so many judges to be judged in the same way,” Nazi Janezashvili says.

According to her, when there are no political motives in the case, the system works properly:

“In simple cases of neighborhood or private disputes, where there are no political interests of the government, the court, of course, remains independent. The independence of a judge is judged by his decisions in politically significant cases.”

Georgian Dream managed to carry out “four waves” of judicial reforms during its rule.

Janezashvili notes several important changes that should have improved the system:

“Among them are the appointment of judges for life, the use of an electronic case distribution system, the opening of court sessions, holding meetings of the High Council of Justice in an open format, as well as conducting interviews with candidates for the position of a judge of the Supreme Court in real time.”

But according to Janezashvili, in parallel with these changes, Dream was making decisions that further subordinated the system to the ruling party. She gives several examples.

“For example, the appointment of judges for life is indeed a guarantee of the independence of a judge, but shortly before that, Mechta transferred the High Council of Justice, which appoints judges, into the hands of the clan. So the fate of the judges was in the hands of the clan.”

Janezashvili also recalls that, for example, the trial of Nika Gvaramia was open:

“The absurdity of the accusation was visible live, but this did not stop the judge from acting from political interests,” she says.

“When we got to the sanctions against judges, this means that what has been done in court since 2012 was not aimed at the result, the result that democratic justice needs,” Janezashvili says.

“A clan is not only a group of people, it is a management model. Kinship-hierarchical relations underlie the management of state institutions. Because of this, the system is closed to many professional personnel. While qualified judges within the system pay tribute in silence. Otherwise they face reprisals,” Giorgi Mshvenieradze says.

The clan controls many aspects of justice. Former judge Anna Gelekva, who was left out of the system due to a conflict with the clan, says the clan can manipulate appointments and after such appointments it becomes clear that the judge is subordinate to the clan, not society.

Nazi Janezashvili points to judges who do not miss the opportunity to take up political cases in order to score points in front of the clan and get a promotion: “Sometimes this becomes a path to an appointment to the Supreme Court.”

Political context

The opposition has long been trying to convince the West of the need for sanctions against members of the Georgian Dream party and its leader, the country’s presumed informal ruler, Bidzina Ivanishvili.

Experts believe that sanctions are a clear political signal to the authorities, which, after the start of the war in Ukraine, stepped up anti-Western rhetoric.

“It is important to emphasize that these are not sanctions against Georgia, but sanctions aimed at protecting the interests of Georgia,” Eduard Marikashvili, chairman of the Georgian Democratic Initiative, said.

In his opinion, the United States makes such a decision in relation to countries where there are clear signs of a decline of democracy and authoritarianism.

Janezashvili says that the US showed that they know what is happening in Georgia.

“This is a kind of mirror for judges, the government – it shows that the situation in the country is quite difficult from the point of view of democracy, and the lion’s share of the problems falls on judges.”

Eka Gigauri, Executive Director of Transparency International Georgia, believes that these sanctions are only the beginning:

“Our partners have told us that we have certainly made progress in 30 years of independence, but the judiciary is an issue that we need to pay attention to.”

Experts believe the court is the main source of power retention.

“Whatever happens in the country, from free elections to violations of human rights, everything ends up in court. By owning the judicial power, you are insured against many issues and can hold power indefinitely,” Eka Gigauri says.

“The more you deviate from democracy, the less you need a well-functioning democratic mechanism, as it prevents you from maintaining power. So everything starts to go the wrong way,” Eduard Marikashvili says.

“Court is always a weapon, a good way to pursue political interests,” Nazi Janezashvili says.

The court is the main pillar of Georgian Dream, whose ratings are at a historic low after eleven years of existence, experts say. A recent public opinion poll showed that the ruling party currently has the support of only 19 percent of the population.

Government officials not only do not support sanctions and comments from the United States, but also defend judges who have fallen under sanctions with particular enthusiasm.

The ruling party rejected three times the opposition’s initiative to create an investigative commission in parliament, which was supposed to investigate corruption in the courts. The initiative was put on the agenda after sanctions were announced.

Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili supported the boycott and said he stood in solidarity with the judges and judiciary under sanctions: “As head of government and representative of the ruling party, I fully support all judges.”

“When they try in every possible way to prevent the creation of an investigative commission and say that this is an act of solidarity, this is unacceptable,” Nona Kurdovanidze, chairman of the Georgian Young Lawyers Association, says.

According to Eduard Marikashvili, the Georgian court and government are now in each other’s captivity:

“On the one hand, the government has a court that will do everything to keep their power. But on the other hand, the clan is already so strong that it itself poses a threat to the authorities. Therefore, the government is not at all satisfied with making the clan uncomfortable.”

What could save the Georgian court?

The Georgian court is not in the best position in the rating of public trust.

A recent study by the International Republican Institute showed that 46 percent of respondents disapprove of the work of the Georgian court.

When asked about the main national problems, the court does not even rate in the top ten.

This is due to the fact that many citizens do not have a direct connection with the judiciary, experts say.

“It is impossible to order a dish that you have never tried. Most of our society does not know what an independent court is. People want the European Union, a good life, they don’t like specific judges — Murusidze, Chinchaladze. They cannot connect their current problems with the current situation in the court,” Giorgi Mshvenieradze explins.

“We must explain to people that without an independent court, we will have difficulties in economic development and European integration. Without a strong and independent judiciary, there will eventually not be enough jobs. After all, the court should contribute to the development of business, and business should create new jobs,” Nazi Janezashvili says.

“People need to understand why they need an independent court. They should know that when they say to high-ranking officials: I will sue you, this statement would be very strong,” Eka Gigauri says.

Experts believe that the involvement of the public, the civil sector, and individual judges, could be a way to save the judiciary in Georgia.

Nazi Janezashvili says there are many good judges in the judiciary who do not like the current situation, although refrain from open protest.

“We must do everything necessary for consolidation, and by this consolidation I mean judges as well. I know it’s hard to imagine, but we need to find allies within the judiciary. We have to give them motivation, encourage them, because it is very difficult to resist the system.”

Nona Kurdovanidze believes that the sanctions can be a positive signal for those judges who conscientiously fulfill their duties: “I believe that they will start protesting out loud.”

Anna Gelekva, a former judge who opposed the clan, believes that its influence is beginning to wane:

“After the decision of the US State Department, they wanted to hold a conference of judges in support of those who fell under sanctions. However, they were afraid and did not carry it out. They were afraid not only of the low number of participants, but also that the opposite opinion would be expressed at the conference. In addition, the trip of individual judges to the United States as part of a training program, despite the decision of the State Department, indicates that the influence of the clan is beginning to wane.”

The former judge imagines the dissolution of the “mafia court” as follows:

“The majority of judges should make a mild protest and separate from the clan. This will lead to the inevitable collapse of the clan, since the government does not need a clan that can no longer control the judges. This will be the beginning of the collapse of the system from the inside, and then its recovery.

“It is the matter of time. The authorities will have to give up judicial control, and the clan members will have to go home. If this does not happen, we will lose the country. I think that the youth will not allow this. We’ve already seen an example of this.”