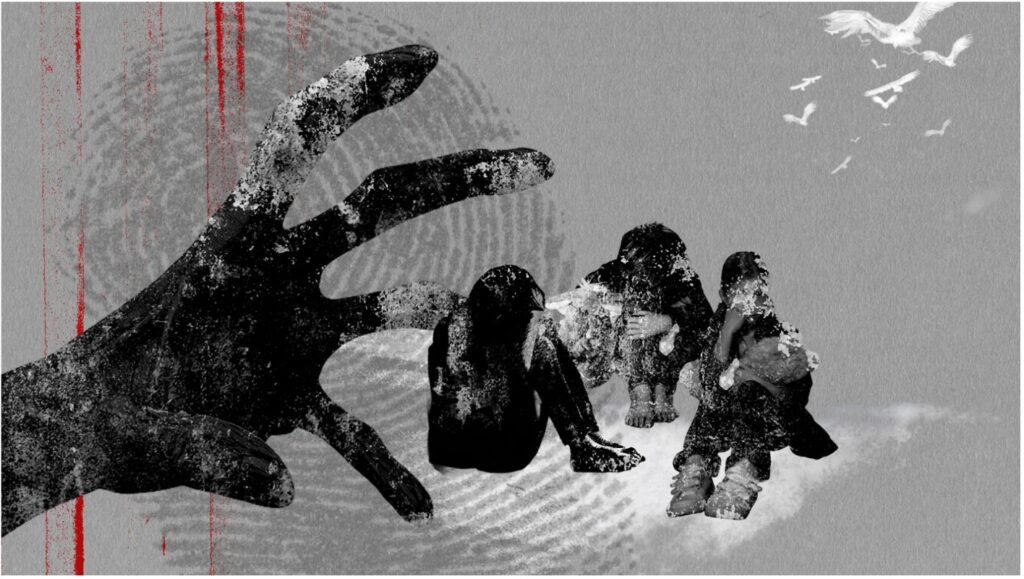

Deported at 14, returned at 17: story of Ukrainians taken by Russia

How Russia abducts Ukrainians

“Honestly, it felt like I was inside some kind of film. But I thank God that nothing worse happened to me. Because it could have. Thank God I’m alive. That’s what matters most,” Denis says.

He is one of thousands of Ukrainian children deported to Russia by occupying authorities. Denis was simply grabbed off the street. For a long, long time, his mother knew nothing of his fate.

When, with the help of the public union “Ukrainian network for children’s rights,” she finally got her son back, she hardly recognized him: she had lost a 14-year-old boy, and met a 17-year-old youth with experiences no adult would wish on anyone.

Speaking with me, Denis often uses phrases that make your heart tighten: “I have nothing to report on this matter,” “at that time I didn’t know,” and so on. These are phrases learned in places of detention, where a sincere word can carry very dangerous consequences. Or when you have to answer countless questions from people who want to slot human suffering into neat boxes: SBU officers, various experts, representatives of the international community.

I’m sorry, Denis, that I’ve brought you back to these burning memories…

Gave blood and fingerprints — and became a Russian citizen

Everything that was happening in Denis’s native village in the Kherson region frightened him and seemed unreal. His mother’s plea not to step outside the gate. The shelling. Russian soldiers repeatedly entering the yard, pointing their weapons at the family, checking documents and inspecting every corner, asking whether there were any weapons.

Then his father was beaten so badly that Denis had to take him to occupied Kherson for surgery. In early autumn 2022, when his father had just been discharged and they were simply walking through the city, armed Russian troops detained them.

“Russian soldiers were stopping people on the street — men, women with children, pensioners. Then they loaded us in groups onto ferries — fenced-off areas about a metre and a half high, lots of armed soldiers. My father and I kept saying we didn’t want to go anywhere, but they told us we had no choice. They loaded us on, took us to the other bank of the Dnipro, to Oleshky. There we had to say our surnames, names, dates of birth, give passwords to our phones and hand the phones over. Everything happened so fast, there were so many armed Russians that I didn’t even manage to call my mother. Then they put us all on large buses and took us to Dzhankoi. I was very scared they’d separate me from my father. He told me not to worry, that the important thing was that we were together, that we’d find a way out and everything would be fine,” Denis says.

According to Daria Kasianova, head of the Ukrainian Child Rights Network, detaining people on the street for subsequent deportation is a fairly common Russian tactic — but only one of many. There are numerous situations in which Ukrainian children end up in Russia against their will.

“For example, some are travelling with parents from occupied territories through Russia to third countries. Russians may detain the parents, arrest them, send them to prison, and simply take the child to a Russian institution. They say: go wherever you planned, but your child stays here. There are cases when Russians enter a home on occupied territory, the child says they live with their mother who has just stepped out to the shop or to collect water, and they take the child anyway — effectively abducting them — and the child then ends up in Russia. And that’s not even mentioning the so-called evacuation of children’s residential institutions to Russia — that’s a separate tragedy,” Kasianova says.

…In Dzhankoi, where Denis and his father were taken, Russians collected palm, finger and footprint samples from everyone, as well as saliva and blood — allegedly in order to prepare identity documents. They were given food — yoghurt, sandwiches, soup, tinned food. Denis says he could finally eat properly and that his father shared his portion with him.

Then, with these new identity documents, Russians transported them further. It turned out to be Krasnodar region. They were moved between different boarding houses, always surrounded by armed guards, restrictions and no explanations. Only statements that Russians had “saved” Ukrainian civilians from shelling by Ukrainian forces. And Russian television propaganda about the “successful” Russian offensive and the “near-total occupation” of Ukraine.

In early 2023, instead of identity documents, they were given Russian passports — stating they were citizens born and residing in Kherson region. They had never applied for Russian citizenship.

“Putin’s decrees have greatly simplified the acquisition of citizenship for residents of Donetsk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions. They receive Russian citizenship automatically, because in Russia’s Constitution these territories are listed as Russian. We once returned a 12-year-old boy who, in the Russian database, was registered as a Russian citizen — even though he had no Russian documents at all. Forced citizenship is Russian policy. It is a way of appropriating Ukrainian citizens,” Kasianova says.

…The Russian passports allowed Denis’s father to obtain a certificate for housing in Russia. But he was frightened by rumours that men registered at such addresses would be conscripted into the Russian army. So father and son took a different approach: using the passports, which gave them limited freedom of movement, they travelled around Krasnodar region in search of low-profile hostels and temporary work.

“We decided from the beginning that we would try to return to Ukraine. But we needed money for the journey,” Denis explains.

Still a minor, he worked with his father at various construction sites. Illegally. As “khokhols” — a slur for Ukrainians — they were rarely hired, and if they were, they were paid far less than Russians. Constant insults, intimidation, threats. To get work, Denis changed the year of birth on photocopies of his documents from 2008 to 2003. This was dangerous: adding five years made him eligible for mobilisation into the Russian army. Police repeatedly demanded that he register for military service in Krasnodar region.

“To avoid drawing attention, we kept moving from place to place. It was very frightening. You didn’t know what would happen the next day, what was allowed and what wasn’t,” Denis says.

Run, because they’ll kill you

By chance, he managed to get in touch with his aunt, who lived in the Russian-occupied part of the Zaporizhzhia region. She urged him and his father to try to reach Ukrainian-controlled territory, saying she had heard something about a “green corridor” in the Vasylivka district.

The journey was grueling: from Russia’s Krasnodar region to occupied Crimea, then to occupied Melitopol, and on towards north-western Zaporizhzhia. At every stage they had to explain to Russian police and soldiers why they were so far from the Kherson region. They lied, saying they were visiting the aunt.

“We could have stayed with my father’s sister, but I really wanted to go home to my mum. And I was afraid the Russians would separate us or mobilise my father,” Denys says.

There were many people trying to reach Ukrainian-held territory through Vasylivka. But Russian soldiers focused on Denys, his father and a few other young men.

“They took me into a tent. They asked what I was doing there, whether I had seen where Ukrainian troops were — all very aggressively, with swearing. Then they slapped me around, basically beat me. One of them forced me to do push-ups and squats — I squatted, and he kicked me. I thought they were going to kill me. I was in shock.

“They were beating my father in another tent. They saw his post-surgery scars and decided he was a wounded Ukrainian soldier. They demanded he reveal Ukrainian positions. They told him I had confessed everything and that they had killed me. I don’t remember how long it went on. Then they let us wash off the blood and told us to disappear from the checkpoint within 10 minutes if we wanted to stay alive,” Denys recalls.

They returned to the aunt’s village. There they took on small jobs to earn at least something for food.

But eventually they had to flee back to the Krasnodar region.

…Denys had told a Russian soldier off outside a shop for swearing loudly in front of children. The next day he was taken to a field outside the village.

“They beat me pretty badly. They asked if I thought I was smart or brave. Then they forced me to apologise to the Russian soldier I had supposedly offended. I refused, and they beat me again — all on camera. I crawled back to my aunt’s house and tried to get medical help. They found out, dragged me back to the field, smashed my phone, beat me again, made me kneel and fired shots near me — bullets flew past. They kept demanding I apologise. And they filmed everything again.

“After that, my father and I just wanted to run. We were afraid that if we stayed in occupied territory, they would shoot us for sure. So we went back to the Krasnodar region — it was safer,” Denys says.

Meanwhile, through Instagram he managed to find his older sister, who was living under occupation. She told their mother he was alive. Their mother contacted the volunteers of the Ukrainian Child Rights Network, asking for help to bring him back from Russia.

According to Daria Kasianova, the organisation most often learns about a child’s deportation from the child’s relatives. Sometimes neighbours who saw the child being taken away report it; sometimes information comes from other children who were returned earlier, from Ukrainian intelligence, the SBU, the children’s ombudsman, foreign partners or organisations monitoring Russian adoption sites.

Daria Kasianova / Facebook

To his mother

“We keep changing the algorithm for returning deported children. Until the end of 2023, we would send mothers or other legal guardians to collect them — this was a requirement set by Russia. But then Russian authorities began detaining and interrogating those mothers, grandmothers and sisters, creating a dangerous situation for the relatives. Now we send specially authorised people who carry all the necessary documents from the child’s legal guardians. They bring the children back to Ukraine through third countries. But if I tell you everything today, tomorrow I won’t be able to extract even one child,” says Daria Kasianova, ending our discussion.

According to her, returning a child is a costly operation. Preparing documents, organising logistics, escorts, accommodation and food all require funding — on average up to $1,500. These expenses are covered by international organisations.

USPR begins planning a child’s reintegration into Ukrainian life as soon as an extraction operation starts. This includes determining where and with whom the child will live once back in Ukraine. If, for example, Denis’s family had still been living under occupation, he would have been placed with a foster family who, together with psychologists, would help him overcome the trauma of his past.

“My mum sent me the number of a volunteer; I wrote to her and forwarded all our documents. Later she bought train tickets to Minsk for me and my father. We boarded — and a week later I was already in Kyiv. Volunteers also helped my father continue from Belarus to Europe. The Belarusian side initially refused to let me through because I was a minor travelling alone. I told them something, pleaded — and they let me into Ukraine. Imagine, while I was gone my mum and stepfather had a baby girl. I got to hold her. At first I didn’t even recognise my mum,” Denis says with a smile.

USPR case manager Natalia Humeniuk, who met Denis at the Ukrainian-Belarusian border, recalls seeing him happy and smiling — and slightly overwhelmed: the teenager could hardly believe he was back in Ukraine.

“You could feel that what he went through in Russia made him cautious in how he spoke, a bit withdrawn. He worried about his father’s safety — his father was still in Belarus. Now that his father is in Europe, and Denis believes they’re both safe, he has opened up more,” Natalia says.

Since meeting him at the border in June 2025, she has been working with Denis: taking him to Kyiv, where his mother now lives; helping him obtain Ukrainian documents, IDP status and the status of a child returned from deportation; arranging state benefits; helping him find a job and register for military service. She also helped resolve his education problems.

The full-scale invasion interrupted Denis’s schooling at the end of Year 7. He did not study while in Russia. Now, at 17, he is catching up.

“He won’t sit at a school desk again — he’s an adult now, a young man who in deportation worked on construction sites, earned money and dealt with adult problems. We offered private tutoring; he tried it but decided to stop. He went to work to help his family. He’s completing school externally,” Natalia explains.

Denis says he is studying online through his village school (his village was liberated in November 2022). His mother arranged for him to enter Year 9 in September. What remained of Year 7 was dropped; Year 8 was lost entirely. But, he says, the situation simply has to be pushed forward. After years of deportation, his Ukrainian has become a bit rusty, but he manages the schoolwork. He now plans to finish Year 9 and pursue secondary and vocational education at the same time.

“Children who were deported or returned from occupied territories have significant gaps in their education. But they have opportunities to catch up. For example, with support from the Canadian government, we can pay for individual lessons in specific subjects. And just over a month ago, our Coordination Centre, together with UNICEF in Ukraine, launched a pilot project in ten schools in Kyiv and Kyiv region with large numbers of such children. The project is implemented by the Ukrainian Network for Children’s Rights in partnership with the Voices of Children charity, which delivers this part of the initiative. Each school appoints a special teacher to help these children adapt, and the learning process is organised according to their individual needs. Overall, during COVID-19 and the war we developed very strong methodologies for helping children close their educational gaps,” says Iryna Tuliakova, head of the Coordination Centre for the Development of Family-Based Care.

Iryna Tulyakova / Instagram

How many have been deported?

“Since the start of the full-scale war, russia has run an intensive campaign to adopt Ukrainian children. Even when children said they had parents in Ukraine, and those parents demanded their return, russia did not send them back. Their surnames, first names, and patronymics were changed, Russian birth certificates were issued — and try to find such a child,” says Darya Kasyanova.

According to lawyer Kateryna Rashevska from the Regional Human Rights Center, after The Hague issued arrest warrants in spring 2023 for Putin and the Russian children’s ombudsman Lyvova-Belova, russia made the adoption process of young Ukrainian children non-public.

“Russians constantly claim that 380 Ukrainian children have been adopted. This number has officially not changed since April 2023. Yet, according to our data, children continued to be placed in Russian families even in 2025. russia simply hides the real figures. Occasionally, information leaks occur — when local Russian officials want to boast about their achievements,” says Rashevska.

Does Ukraine know the total number of children deported to russia — whether adopted or placed in Russian orphanages?

Rashevska says no. In Ukraine, there is no legal distinction between children deported to russia and children moved within the occupied territories, for example from Kherson to Melitopol. In both cases, children’s rights are considered violated equally.

“In the Ministry of Justice there is a register of deported and forcibly displaced children. On the ‘Children of War’ platform, it shows 19,546 children. A special commission at the Ministry of Justice checks the information on each child listed in the register. The downside of this register is that it is closed to parents and the public. On the ‘Children of War’ platform, you can enter a child’s full name to see if they are in the register, but you cannot view the entire list. Only a legal representative — parents or guardians — can request an extract. This limits the ability of NGOs and volunteer groups to work with the data,” Rashevska explains.

The lawyer believes the figure of 19,546 children needs careful verification. It is possible, though difficult, to determine how many children from orphanages or foster families were deported or relocated. It is also possible to estimate the number of children living with parents who went missing — and could have been deported — as parents report these cases to the relevant state authorities. But it is much harder to determine how many children became orphans due to Russia’s military actions and were then deported, as there is no one to report these cases after the parents’ deaths.

According to Rashevska, in Ukraine, many cases are often called deportation even if legally they are not. For example, if a child’s legal guardian took them to russia, it is considered a family matter, not deportation, even if the child does not like being in russia. But if russians tell Ukrainians to leave through evacuation corridors and simultaneously transport them to russia, this counts as deportation.

“Deportation involves coercion. Coercion does not only mean a gun at your temple; it can also mean circumstances in which you cannot freely make a decision. For example, if russians provide only one evacuation corridor — say, to Taganrog — and from there people are taken to Vladivostok or Novosibirsk, this is not evacuation, it is deportation. Recall Lyvova-Belova’s words in April 2023, when she said that 730,000 Ukrainian children crossed the Russian border via such ‘evacuation’ routes. Therefore, the figure of 19,546 children needs verification,” Rashevska concludes.

Russia manipulates. But what about us?

Sometimes the Ukrainian side can arrange for a child to be returned from Russia, but the child doesn’t want to go, because the Russians have convinced them that as soon as they cross into Ukraine, they will be taken to an orphanage and their mother will be executed.

But usually, the situation is different.

“Russia does not return our children, even when international organisations or our foreign partners are involved. Here’s an example I always use: a group from Donetsk region, 31 children deported by Russia to the Moscow region in May 2022. So far, only six or seven have been returned,” says Daria Kasyanova.

According to her, among those working to bring Ukrainian children back from Russia, the greatest enemy is… time.

Children deported at a young age do not remember their life in Ukraine or their relatives. They grow up immersed in the Russian environment, which becomes familiar to them.

There is a relevant UN Convention, ratified by Russia many years ago, stating that a child has the right to know their origins. In theory, Russian adoptive parents should tell a deported Ukrainian child the truth about their biological parents if asked. But will the child ask? And will the parents tell the truth?

“These children grow up calling other Russians ‘mom’ and ‘dad’. How do we ensure that returning to Ukraine doesn’t cause them more trauma than being raised in a Russian family? That’s a private matter. But the Ukrainian state cannot accept the legality of transferring its citizens to Russian families. There must be international legal mechanisms to validate such decisions in the best interest of the child.

We have two options. Either ignore the process, pretend these children don’t exist, and let them grow up in Russian families—after turning 18, they will likely choose not to return to Ukraine, as they’ve grown up with a Russian identity. Or we can try to organise their return while protecting the child’s rights. This requires cooperation with Russia, and Russia refuses to cooperate,” concludes Kateryna Rashevska.

She notes that after World War II, Poland managed to return only 10–15% of its children taken to Nazi Germany, even though Germany was occupied by allied forces and Poles could search almost every home. Even then, the victors did not agree on child repatriation. The USSR insisted on unconditional return, while allies recommended assessing what was in the child’s best interest—if a child was better off in a German family than in an orphanage, why take them home?

“Today, Russia manipulates the issue of deported children in its favour: it claims it will only return a child to biological parents or legal guardians, not the Ukrainian state. And in these manipulations, it succeeds. For example, of 48 children from the Kherson regional orphanage, only seven have been returned to Ukraine. These children were aged from a few months to four years. Russia claims Ukrainian children do not want to return. But a child’s expressed preference does not equal their best interest. Being turned into cannon fodder for Russia is clearly not in the interest of Ukrainian children,” says Kateryna Rashevska.

However, she notes the situation is slowly improving. On 17 October 2025, the International Committee of the Red Cross issued a commentary on the Fourth Geneva Convention, stating clearly that a state claiming to have evacuated children must immediately return them to their country of origin. Otherwise, it constitutes deportation—a violation of the Geneva Conventions.

Although this commentary does not mention Russia specifically, the implication is clear…

By the time of writing, Ukraine had managed to return 1,791 children. How many were deported to Russia versus relocated within occupied territories is unknown. Both categories are not distinguished in official statistics. Denis is among them.

He says his deepest wish now is to join his father in Europe: “I want to be with my father, then live, enjoy life, develop, and forget everything we had to go through. I will finish school—after that, everything is in my hands.”

The report was produced with support from Mediaset.

How Russia abducts Ukrainians