Azerbaijan-Russia: why they can’t be on friendly terms with each other

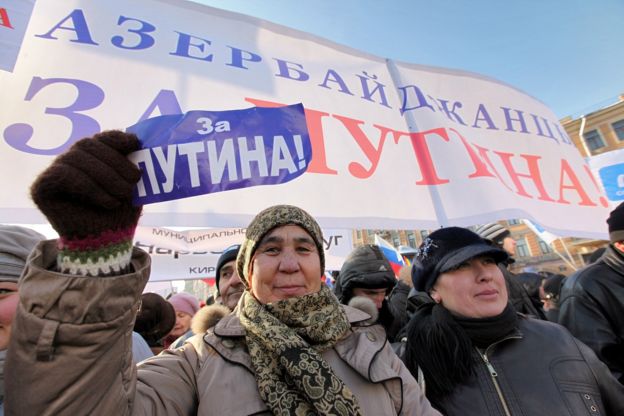

Russia-Azerbaijan relations are deteriorating, and political analysts fear that it could lead to some serious consequences, as Baku depends on its ‘Big brother’ in the political, economic, migration and energy issues.

The matter concerns numerous spheres, including the military-political sphere, where the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict plays an important role, the economy, where Russia is a major consumer of Azerbaijani products, migration, as over 1.5 million Azerbaijani citizens are permanently residing in Russia, as well as the energy sphere, where both countries supply energy to Europe where Russia can and does influence market conditions.

The causes of deterioration

On 20 July, the Baku City Court sentenced Alexander Lapshin, a Russian blogger, to three years in prison. Earlier, the latter had visited the unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR) and was ‘blacklisted’ by the Azerbaijani Foreign Ministry. Despite that, he later traveled to Azerbaijan using a Ukrainian passport, where his name was somehow written differently. As a result, he was sentenced for trespassing the state border.

Obviously it’s not the best year for the two countries’ relations, in general.

In May this year, the Russian court dissolved the All-Russian Azerbaijani Congress, the most renowned Azerbaijani diaspora organization in Moscow, which had been operating since 2001. Moscow received an indignant reaction from the Azerbaijani Foreign Ministry, as well as from the President’s aide, Novruz Mammadov.

The Russian Foreign Ministry responded to it as follows: “We don’t need any dubious advice on how we should build inter-ethnic relations in our own country.”

The two countries’ Foreign Ministries exchanged barbs on other matters as well: for example, on the case of Dilham Askerov, a Russian citizen who was sentenced to life in Karabakh for being an Azeri spy and saboteur.

Maria Zakharova, a spokesperson for the Russian Foreign Ministry, termed the Azerbaijani media’s behavior as ‘blatant rudeness’. In response to that, the Azerbaijani pro-governmental media outlet, 1news.az, referred to the Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson as ‘a backstreet diplomat’.

The situation was further aggravated by yet another escalation of tension on the line of contact in Karabakh on 4 July. Two civilians, including a 2-year-old child, were killed in shelling on the Azerbaijani side.

The next day, the Russian Foreign Ministry issued a statement condemning the non-admission of ethnic Armenians, citizens of Russia, to Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan perceived this statement as an attempt to ‘pass the buck’.

“Today we are dealing with a kind of cold war,” says Grigory Shvedov, a Russian human rights activist and journalist, and editor-in-chief of the Caucasian Knot media outlet. “In fact, Russia-Azerbaijan relations haven’t seen an upswing for quite long. We could see how the Foreign Ministry is defending Lapshin, which has never been the case with regard to other Russian citizens.”

In the expert’s opinion, the weapons supplied by Russia could be a factor of influence and pressure on Azerbaijan: it can assume different quality in case of certain aggravation.

Touching upon the developments in the past few months, Hikmet Hajizade, the Azerbaijani ex-ambassador to Russia, stated that there had been similar scandals earlier, and that they usually ended with a semblance of truce. “But there actually has never been any friendship between our sides. It all comes down to the imperial ambitions, Russia’s desire to subordinate Azerbaijan, to deploy troops here under the pretext of the peacekeeping contingent,” the diplomat believes.

According to Hajizade, Russia has many means of exerting pressure on Azerbaijan in general. And it’s not just the matter of military superiority, but the tightly linked economies of the two countries.

Chained together

The Federal Migration Service (FMS) claims that 523 000 Azerbaijani nationals have been staying in Russia since the beginning of this year, whereas according to the 2010 population census data, 603 000 ethnic Azerbaijanis resided in the country in the reporting period. According to the RF Central Bank data, USD 1.2 million are transferred from Russia to Azerbaijan annually.

In addition, Russia is a major client for Azerbaijan’s non-oil exports. According to the Azerbaijani State Statistical Committee data, USD 409 million worth in commodities (mostly fruits and vegetables) were exported to Russia last year.

“Russia accounts for 10% of Azerbaijan’s total exports, with 70% of Azerbaijan’s agricultural products exported to Russia. Therefore, there is a certain economic dependence. Russia has already used economic leverage for exerting pressure on other countries, especially when banning imports of goods.”

Although Azerbaijani authorities are well-aware of the aforesaid, they don’t make any efforts to introduce agricultural products to the European market and thus reduce the country’s dependence on Russia.

“Azerbaijan has been dragging its accession to the WTO for many years. But membership in this organization is one of the preconditions for importing into the EU,” says the economist. “However, the country doesn’t take this step, because the WTO requires improving the quality of goods and customs operation. As a result, Azerbaijan becomes economically vulnerable to fluctuations in Russia.”

The expert’s words were confirmed by the developments at the end of March, beginning of April this year, when Azerbaijani freight drivers couldn’t cross the Russian border for several weeks. They were blocked by Russian long-haul truck drivers, who tried to persuade their Azerbaijani colleagues to join their protests against a new tax collection system ‘Plato’. It all resulted in fistfights and vehicle damage.

“Essentially, Russia and Azerbaijan are bound by common game rules which are accepted by both the country’s leadership and ordinary greengrocers trading in the Russian market. None of the sides aspire to join Europe,” said Jafarli.

However, the low-skilled workers (the aforementioned ‘greengrocers’) aren’t the only category of people who travel to Russia for work or move there forever.

Marina Aliyeva, an Internet-marketer, is going to move to Moscow end of this year. Before that, she has taken a couple of Russian paid courses in her major. “I’m leaving for two reasons: I will be paid three times more there than here, and also, here we don’t use technologies and methods of doing business that are applied there. I’m actually leaving for the sake of higher salary and career development.”

Energy is one more aspect of the Russian-Azerbaijani relations. In this sphere, the countries are no longer partners, but rather, rivals.

The Southern Gas Corridor, which is being constructed now, is probably one of the most ambitious energy projects for Azerbaijan in recent years. Its total cost amounts to USD 45 billion. It is expected that, starting from 2020, natural gas will be supplied through this pipeline to Europe via Georgia and Turkey, i.e. bypassing Russia. In the long run, it will be connected to another ‘bypass’ gas pipeline project, TAP (Trans-Adriatic gas pipeline), which will reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas.

However, it seems that Moscow doesn’t like the project very much. There are protests against the pipeline in Europe. One of the initiators of the protests is the Italian ‘Five Star Movement’, a political party that makes no secret of its pro-Russian moods.

Apart from this, Russia is also pushing through its own project, the Turkish Stream (or TurkStream), which is targeting the same market as the TAP project – in other words, it is actually creating an alternative to the alternative.

Generally speaking, Russia is negative about the gas pipeline project involving Azerbaijan.

Alexander Medvedev, the Deputy Chair of Gazprom JSC, stated last year that Azerbaijan was unable to fill the pipeline with gas, and that Russia, in this regard, remained the best alternative for Europe.

http://www.bbc.com/russian/features-40683693?ocid=socialflow_facebook