Azerbaijan joins Central Asia advisory council: what it means for South Caucasus

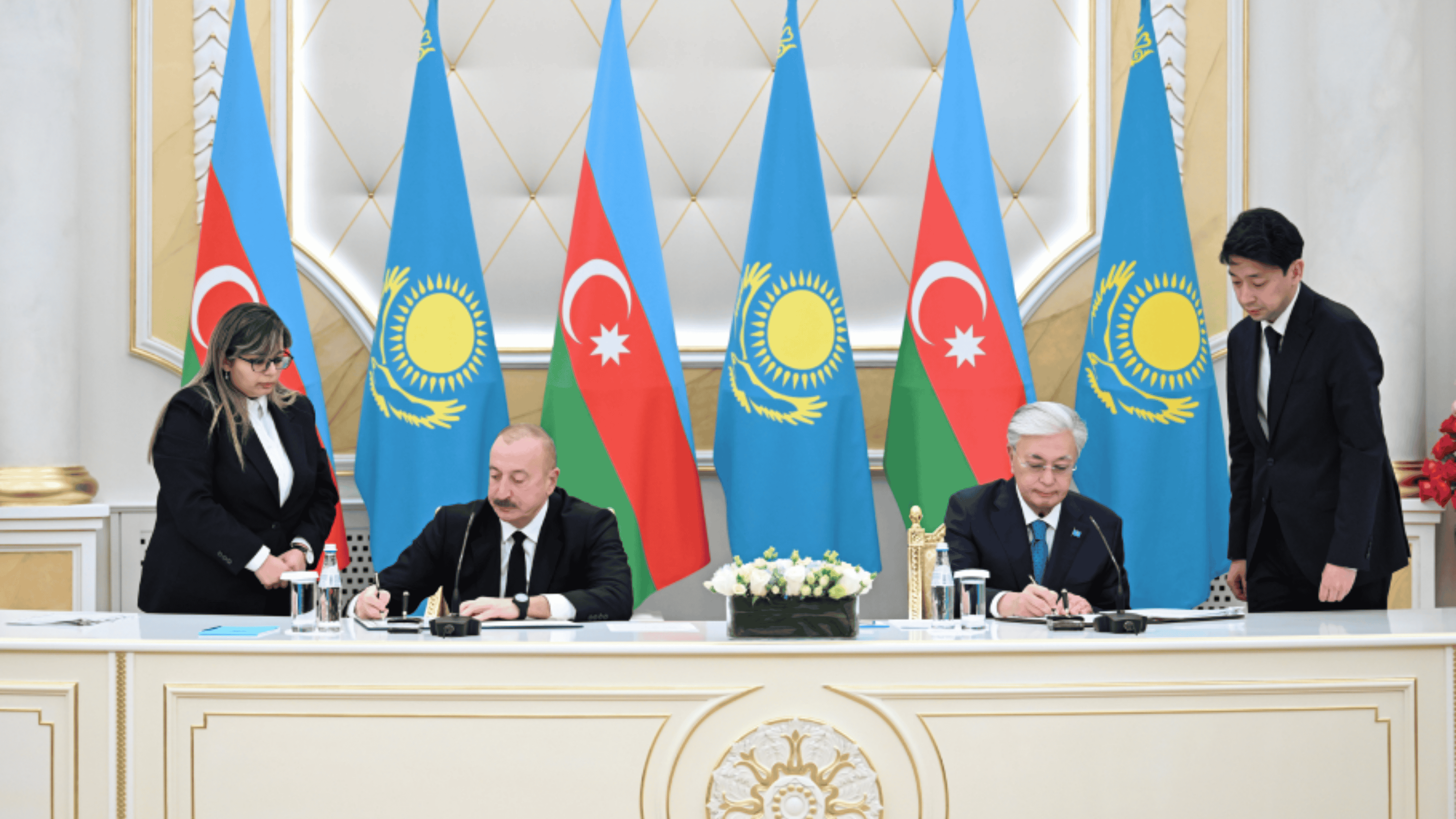

The seventh consultative meeting of Central Asian heads of state, held in the Uzbek capital Tashkent, delivered significant news for Azerbaijan.

Participants agreed to admit Azerbaijan to the consultative framework as a full member.

Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev described the decision as a historic moment.

“Bringing Azerbaijan into the format will help build a solid bridge between Central Asia and the South Caucasus and create the conditions for a shared space,” Mirziyoyev said.

The summit, where Ilham Aliyev delivered an address, was presented by official structures in Baku as an important success for the country’s foreign policy.

Many observers argue that Azerbaijan’s entry into the Central Asia consultative format paves the way for a rethink of its role in the wider region.

The commentary was prepared by a regional analyst. The terms, place names, opinions and ideas used represent solely the views of the author or a specific community and do not necessarily reflect the position of JAMnews or its staff.

Motives behind Azerbaijan’s push for integration with Central Asia

Azerbaijan’s decision to join the consultative meetings of Central Asian heads of state is driven by a mix of political and economic motives.

1.

After resolving the Karabakh conflict, which lasted for nearly three decades, and restoring its territorial integrity, the country began to redefine its foreign-policy priorities.

The government continues to promote what it calls a long-standing policy of “balanced foreign relations”, avoiding full alignment with either the West or Russia.

Against the backdrop of Russia’s war in Ukraine and intensifying competition among major powers, Central Asia has come to be seen in Baku as a relatively neutral, stable and promising direction.

For Azerbaijan, the region offers a convenient platform to pursue national interests without being forced to choose between Moscow and Western capitals.

2.

Economic, energy and transport considerations have also been decisive.

In recent years, the Trans-Caspian transit route — known as the Middle Corridor — has moved to the forefront, promoted as an alternative to traditional northern routes running through Russia.

Through this corridor, Azerbaijan and the Central Asian states are becoming key links in cargo transport between East and West.

President Ilham Aliyev has repeatedly said that freight volumes along the Middle Corridor through Azerbaijan have grown by 90% over the past three years — a figure seen as evidence of the region’s rapidly expanding logistics potential.

Participation in international transport projects together with Central Asian countries allows Azerbaijan to increase the flow of trade crossing its territory.

Baku recognises that the more efficient and secure the Central Asian states’ access across the Caspian to China, South Asia and the Middle East becomes, the higher Azerbaijan’s transit revenues and strategic importance will rise.

Energy expectations

Central Asia holds substantial oil and gas reserves, and Azerbaijan — with its existing energy infrastructure, including the TANAP pipeline and the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan route — is well placed to play a role in moving these resources to Western markets.

The idea of linking the energy networks on both sides of the Caspian has been discussed for many years. Participation in the current format gives Azerbaijan new opportunities to deepen cooperation with Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan in energy exports.

Regional integration also broadens Azerbaijan’s potential to increase its own non-oil exports to Central Asian states and to attract investment.

Large amounts of funding from international financial institutions — including EU programmes under the Global Gateway initiative — are being channelled into joint transport and infrastructure projects such as modernising the Middle Corridor or building new railway lines.

What opportunities does this open up?

First and foremost, this membership boosts Azerbaijan’s authority both regionally and internationally.

As a full member, Baku can now participate directly in decision-making processes among Central Asian states and exert a direct influence on developments in the region.

Thanks to its geographic location, Azerbaijan is a natural bridge between Europe and Asia. This role now enjoys official regional recognition and could evolve into more coordinated projects with Central Asia.

At the Tashkent summit, regional leaders already discussed a roadmap for economic integration and joint transport projects in Central Asia through 2035.

If these meetings lead to the adoption of common transit and logistics standards, as well as unified customs and digital solutions, freight movement along the Middle Corridor could speed up, potentially increasing national revenue.

Political support may also strengthen for long-discussed projects, such as the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline.

In addition, cultural and humanitarian ties are expected to flourish, with possible joint programs in education, tourism, and technological cooperation.

Potential risks

Central Asia remains a region where the interests of major powers — including Russia, China, the US, and Turkey — intersect. By deepening cooperation with this region, Azerbaijan inevitably needs to take the positions and demands of these countries into account.

In particular, closer engagement within the Central Asian consultative format could be perceived by Moscow as a political alignment of Turkic-speaking states.

Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, in an article published ahead of the Tashkent meeting, stressed:

“We do not want anyone to impose their model of governance or their own rules of the game on us. Cooperation must be built solely on an equal footing and without interference in each other’s internal affairs.”

This indicates that the Central Asian states are not aiming to create any externally controlled or federative structure and intend to maintain flexibility in the format.

If necessary, neighbouring powers such as Russia and China can be invited to participate as guests. Back in 2022, Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev suggested inviting Russia and China in such a capacity.

On one hand, this underscores that the format is not directed against any specific country. On the other hand, it requires Azerbaijan to be ready for dialogue at the table with major global players.

Currently, the consultative meetings of Central Asian heads of state are not a full-fledged integration organization. Decisions made within this platform remain largely advisory.

Political analysts warn that Azerbaijan’s new status could remain largely symbolic. Despite full membership, its influence on decision-making may still be limited.

At the Tashkent meeting, Mirziyoyev proposed formalizing the consultative meetings into a permanent platform called the “Central Asian Union.”

If this proposal is implemented, Azerbaijan’s voice in the new body would carry weight, and decisions would be backed by concrete commitments.

Otherwise, the meetings risk becoming annual events where leaders issue declarations of intent, failing to meet expectations.

Resource and adaptation risks

For deeper cooperation with Central Asia, Azerbaijan will need to dedicate economic, financial, and human resources.

For example, the regional states are discussing plans to increase trade turnover and create a joint “Made in Central Asia” brand. If Azerbaijan wishes to participate fully in such initiatives, it will need to adapt its business environment and industrial sector.

In addition, each Central Asian country has its own internal priorities.

Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are members of the Eurasian Economic Union with Russia, while Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan belong to the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Turkmenistan, meanwhile, traditionally maintains a policy of permanent neutrality. This means that even within a common platform, differing foreign-policy orientations persist.

Azerbaijan will need to advance its interests in ways that avoid touching on partners’ sensitive issues.

Internal regional challenges also pose risks. Disputes over water resources, border conflicts, or market competition could require Azerbaijan to take on a mediating role.

Azerbaijan draws closer to Central Asia