"Artists have always lived in hardship." The story of an artist from an Azerbaijani province

The story of artist Najmeddin Huseynov

Hikmat Nazim

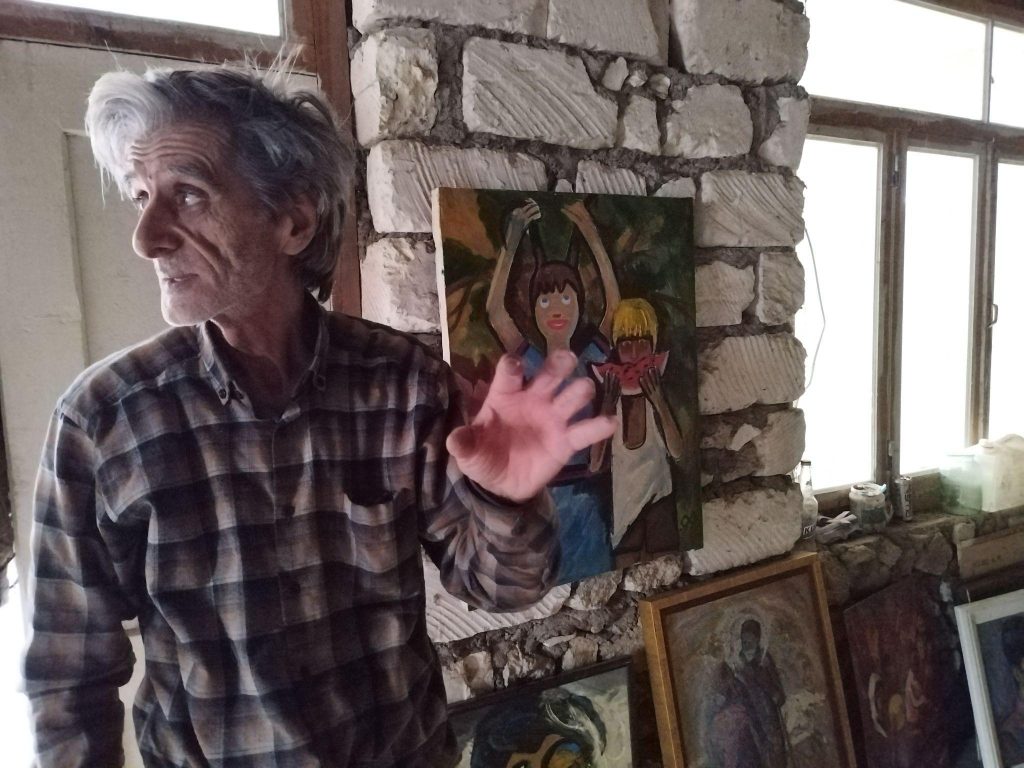

Artist Najmeddin Huseynov sits in front of an empty easel and looks at his dusty works stacked on top of each other on the floor. His son Taleh, who listens to our conversation, sometimes takes pictures of us and says: “They are preparing a photo essay about my father.”

Huseynov says that his son is always like this: when someone comes to prepare a report about his father, to interview him, he sits in the corner and listens, or takes pictures for the Instagram account dedicated to his father.

- Russian children in Georgian schools – where they study and what problems the state has faced

- How to keep labor migrants in Armenia? New EU proposal

- “Everyone wakes up to the sound of adhan, and we to the sound of the anvil”

Huseynov was born in 1955 in the village of Chaily, Gazakh region. Graduated from Azerbaijan State Art College.

The man who speaks the language of the palette, inspired by the fairy tales that his grandmother used to tell him in his childhood on long winter evenings, is now completely gray. He often does not even have enough money to buy canvas and paints for work. In the studio he sits in front of an empty easel and thinks, or returns to some old work, adds details that he missed.

He lives in the village where he was born. In his house, the repair of which he could not finish. More precisely, in the workshop he created in one of the rooms.

He is a member of the Union of Artists of Azerbaijan, the Union of Professional Artists of Russia, an honorary member of the International Academy of Contemporary Art, and a full member of the European Academy of Natural Sciences. But his whole life is in this cramped room-workshop, in which it is impossible to take a step and not stumble upon his work.

He shows his diplomas, honorary titles, documents confirming membership in academies and unions, which he hung on the wall, and insistently says: “Take a picture of this too.” He points to a paper with the inscription “Certificate of Honor”: “This is the first award …”

“Sometimes a person feels very unnecessary, he doesn’t even want to live… People around make you feel like this…”

I met my friend Sakhavat on the way, and told him: “I’m going to talk to Najmeddin, let’s go together.” And when Sakhavat asked the artist a question about a picture he saw in an art album from the shelf, the pain of the artist was revealed:

“Your friend is trying to read and understand the picture, it’s nice, we would be very bored if it was someone else who doesn’t care about art, and through him we learned something new in art…”

He suddenly asks: “Have you seen my cartoons? I see that you are interested in reading the pictures, let’s read them a little.” He took the dusty papers that were piled on the floor and spread them on out.

He is trying to help us, because we can hardly “read” the drawings: “Look, he is a neurologist, he has a hammer in his pocket”, “Don’t you understand, they greeted each other, the adult man is very talkative, the boy was bored, so he turned away and left, but his glove remained in the old man’s hand,” we laugh and he invites us into the next room.

As we enter, another world opens before us. All the works the artist has created so far are collected in this room with cobwebs hanging from the unfinished ceiling and damp walls.

Najmeddin doesn’t like to complain about his difficulties. When his son Taleh tries to list the problems, he interrupts him. The artist believes that art is above all. “Artists have always lived in suffering and deprivation…” he says.

He is not embarrassed by the dampness of the room where the works are stored, the cobwebs hanging from the ceiling, even the fact that his works are already deformed due to poor conditions. He still tries to neatly arrange the paintings so that they come out beautifully in the photographs. “A little sloppy, sorry…” he tells us with a guilty expression on his face.

Suddenly something comes to mind. He goes to the door, takes one of the paintings from the bottom of the wall, and holds it in his hand: “My son put this painting on an American site. A buyer was found, offering $1,000. We thought that half of this amount would be spent on sending the painting from Azerbaijan to America, so I changed my mind and did not sell … “

At this moment my friend Sakhavat intervenes, asking if it is better to sell the paintings than to keep them at home? Najmeddin smiles and says that they are not paying a price that is acceptable to him: “It is better for them to die in front of my eyes than to sell at such a price. At least I will work on them when there is time, I will prolong their life while I myself live … “.