Armenian-Azerbaijani border, security and journalists

Armenian journalists working near the Armenian-Azerbaijani border

For more than a year, Armenian journalists have had to obtain permission to work in some settlements of the Syunik and Gegharkunik regions.

The restrictions were introduced even before the 44-day war, in August 2020, when amendments to the Law on the State Border came into force, thereby prohibiting video and photo recording of the border area, as well as “engineering structures and barriers located on the border strip and used by the border troops; buildings, structures, observation towers, vehicles”.

The authorities justified the need for changes. The statement of the National Security Service of Armenia, adopted after the amendment, emphasized that the footage taken by the residents of the border or tourists with the help of video cameras and drones does not escape the attention of the border guards of the neighboring state – Azerbaijan.

Such filming may, according to the NSS, have a negative impact on the security of the border, as footage may end up on social media, where Azerbaijani special services can see it.

- Closed railway of my childhood and the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict

- “They should know that we have an enemy” – children and the Karabakh conflict

- Club stand-up returns to Yerevan

Additions to the law would have gone unnoticed if there had not been another statement from the National Security Service – this time on February 10 last year. It noted that for security reasons, journalists would need to obtain special permission from the national security authorities to work in the “relevant territories” of Syunik.

The statement was made after a serious aggravation on the border and amid rumors about the possible beginning of the process of delimitation and demarcation between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Many journalists and human rights activists, however, believe that the NSS has not provided sufficient legal grounds for restricting their activities.

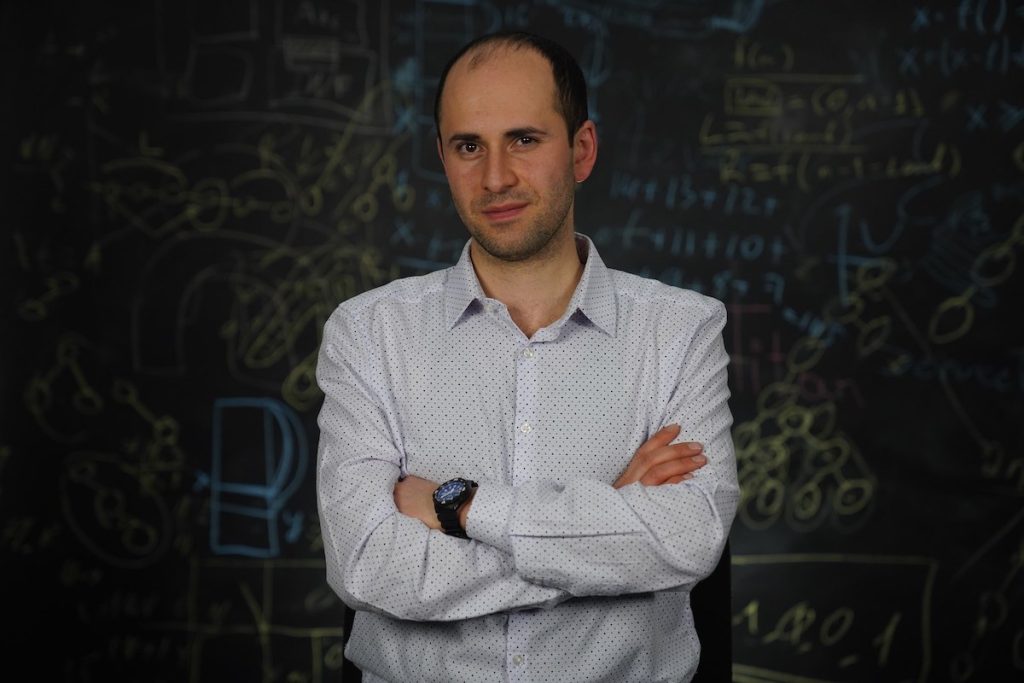

One of the journalists who travel frequently to the border areas, Gevorg Tosunyan of the popular civilnet.am media resource, says restrictions on journalists’ work in the early post-war period were often arbitrary.

So, in order for the film crew to be able to enter the village of Shurnukh, which after the war was divided into two parts, it was necessary to obtain permission from the border troops of the National Security Service.

“If you applied in advance, then it would certainly be possible to work on the spot, but there was another problem.

When the situation at the border escalates, a journalist needs to immediately be on the scene to carry out their professional activities.

But they are simply not allowed to do this, and get reminded of the need for permission. And obtaining a permit usually takes more than a week”, says Tosunyan.

But there is also a second problem. Permission in different parts of Armenia must be obtained from different structures. So, in Syunik they are issued by the National Security Service, in the Gegharkunik region – by the Ministry of Defense.

So, Tosunyan was denied permission to record in the border villages of Gegharkunik, citing the fact that the situation there was tense.

“The situation in these areas after the war is almost always tense, and yet the voices of the people living there should be heard”, the journalist believes.

He is convinced that cooperation between the state and journalists can be more effective. Those reporters who are ready to go to hot spots are unlikely to spread disinformation – they need objective information.

But it is very difficult for his colleagues, who are hundreds of kilometers away, to verify the authenticity of the information transmitted to them and the reliability of the source.

Tosunyan’s colleague David Galstyan also often travels to the border areas and seems to know all the roads leading to the villages located close to the borders.

“I think coverage of the situation in these villages is very important”, Galstyan says.

He traveled to the border many times and almost never got a travel permit. However, he never had any problems after the publication of materials prepared during these missions.

“In addition,” he emphasizes, “the communities that are subject to restrictions are not specified, which means that this clause of the law can be used by the NSS and the Ministry of Defense to prevent journalists from working in any villages close to the border”.

“I have certain internal principles, rules that I always follow. I know what can cause damage, create problems in terms of border security. Naturally, my colleagues do the same.

I have my own internal mechanism of self-regulation, which I am guided by. I am not interested in scandalous news from the border, I am more interested in the problems of people living in border villages”.

David Galstyan argues that the restrictions are meaningless and ineffective, and sometimes even reach the point of absurdity. For example, it is forbidden to shoot indoors where it is impossible even to accidentally shoot any military facility.

“If the NSS and the Ministry of Defense see a problem in the filming conducted by journalists, then in fact, the main leak of information comes through photos or videos taken by local residents or soldiers serving in the same area.

Professional journalists, especially after the war, know what and how to film, so that there is no way to understand where it was filmed”, says David Galstyan.

Chairman of the Committee for the Protection of Freedom of Speech Ashot Melikyan shares the concerns of journalists and notes that the new restrictions have made their work more difficult. At the same time, Melikyan advises treating them with understanding.

“Of course, the work of journalists covering the life of border settlements has become more complicated, but after the 44-day war, new realities have to be taken into account.

Journalists took these restrictions painfully, but after the war the borders were moved and all the restrictions that applied to other border areas extended to new points.

Yes, bans create difficulties for journalists, but there is an objective reality that cannot be ignored”, Melikyan says.

However, according to him, it makes sense to reconsider these restrictions, creating a clear regulatory mechanism instead. For example, if journalists want to cover the daily life of the border areas, SNB officers should support and accompany them, limiting their filming of military or other strategic installations.