How to live when the power’s out. Stories from Abkhazia

Abkhazia is in the midst of a severe energy crisis. Rolling blackouts were introduced on November 15, during which time there is no power for several hours a day in different areas at various times. Residents of Abkhazia have to adapt to life in these conditions.

Astanda

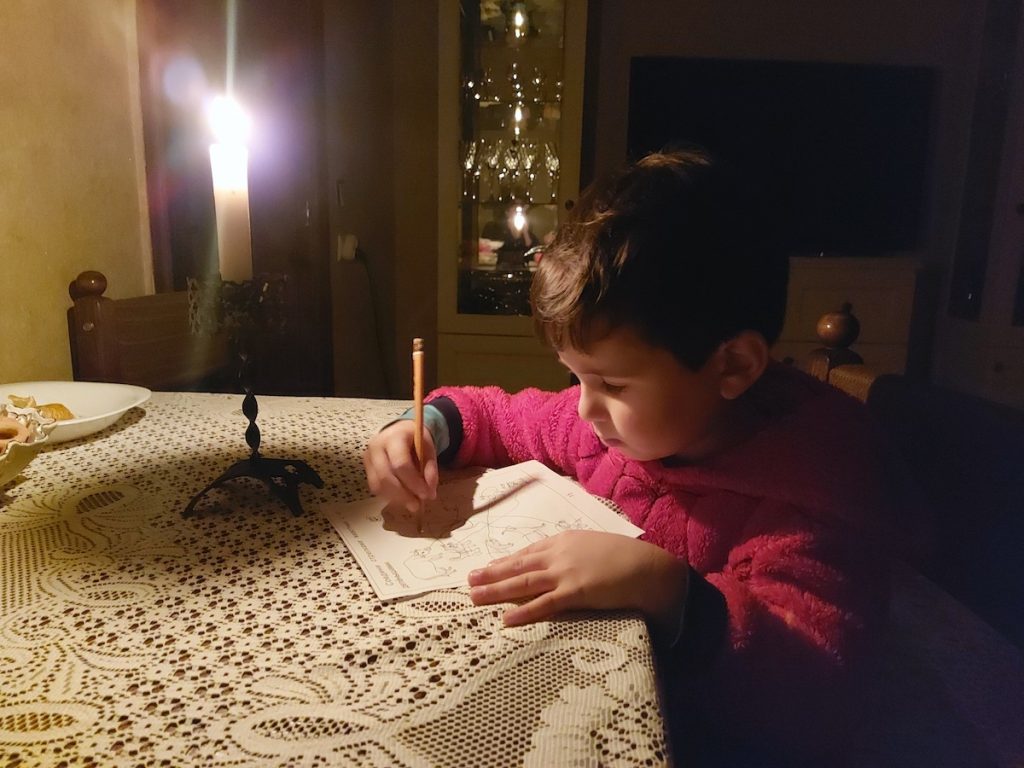

Astanda Jalagonia wakes up every day at six in the morning. She needs to make breakfast before the power is cut. She cooks porridge and wraps her five-year-old son in three blankets to keep warm. For the younger half-year-old, she prepares boiling water in a thermos in order to make a milk mixture after he wakes up.

The children usually wake up at eight, just at the time the electricity goes out. There is no power until 10:00, because this is how the schedule of the energy company Chernomorenergo is drawn up. But even after 10, it is not turned on, because every time there are some problems on the line.

“We spent the whole weekend without power. It was evident that the power engineers were fixing something, the power was turned on several times, but it went out again,” says Astanda.

- Op-Ed: Abkhazia without electricity and business above all

- Rolling blackouts return to Abkhazia following failure to rein in cryptocurrency mining

- Op-Ed: Abkhazia needs Russian money, but it might come at a high cost

Eleonora

Astanda’s neighbor Eleonora Giloyan didn’t meekly wait for the light, she called Chernomorenergo and the Sukhumi power grids in the hope that ‘if she didn’t sit in silence, the problems would be resolved faster.’ On another call from Eleanor to SUES (Sukhumi power grid management), she was told that they could not turn on the power because the network simply didn’t have the capacity, because there is a cryptofarm at the former leather factory nearby.

“Well, turn it off,” the girl shouted into the phone. And at the other end they answered: “If we could.” Eleonora Giloyan told this story to her friends and published it on Instagram.

“You have no idea how many people responded to my publication,” she says. “People began to write me the addresses and names of the owners of the mining farms.”

It is the cryptocurrency mining farms that are considered the main culprits of the energy crisis in Abkhazia.

Eleanor collected all the data and handed it over to the police. On Wednesday, November 24, one of these addresses was raided. As a result, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the State Security Service and Chernomorenergo de-energized the crypto-farm in the building of the Sukhumi Institute of Physics and Technology.

Denis

Denis Solomko’s family invested 2.5 million rubles [about $33,000] in the construction of a new farm. His parents were engaged in agriculture all their lives. The crisis due to the coronavirus pandemic forced Denis to start to till the ground. Everything was going well, the farm was developing. But a new crisis broke out – the energy crisis.

Rolling blackouts for six hours a day disrupted the entire technological process on the farm. In the incubators, 2,300 quail eggs have gone bad.

“If the power was turned off only on schedule, the tragedy would not have happened,” says Denis, “but because of the rolling blackouts themselves, permanent accidents began to occur, the power was no longer available at the prescribed time, and the incubation process was interrupted.”

According to Denis, their direct losses amounted to 23 thousand rubles [about $300], and the lost profit was about 150 thousand rubles [about $2,000].

But, as the young farmer says, this story has become a lesson for them.

“I should have bought a diesel generator earlier. And we all put off this waste, directing our free finances to equip the farm”, says Denis. “we bought it anyway, but only after losing money and the ability to earn.

And we are not alone. Everyone who is engaged in production, trade, warehousing today, if they do not suffer significant losses, as they lose most of their income, because part of the profit needs to be spent on fuel for generators.”

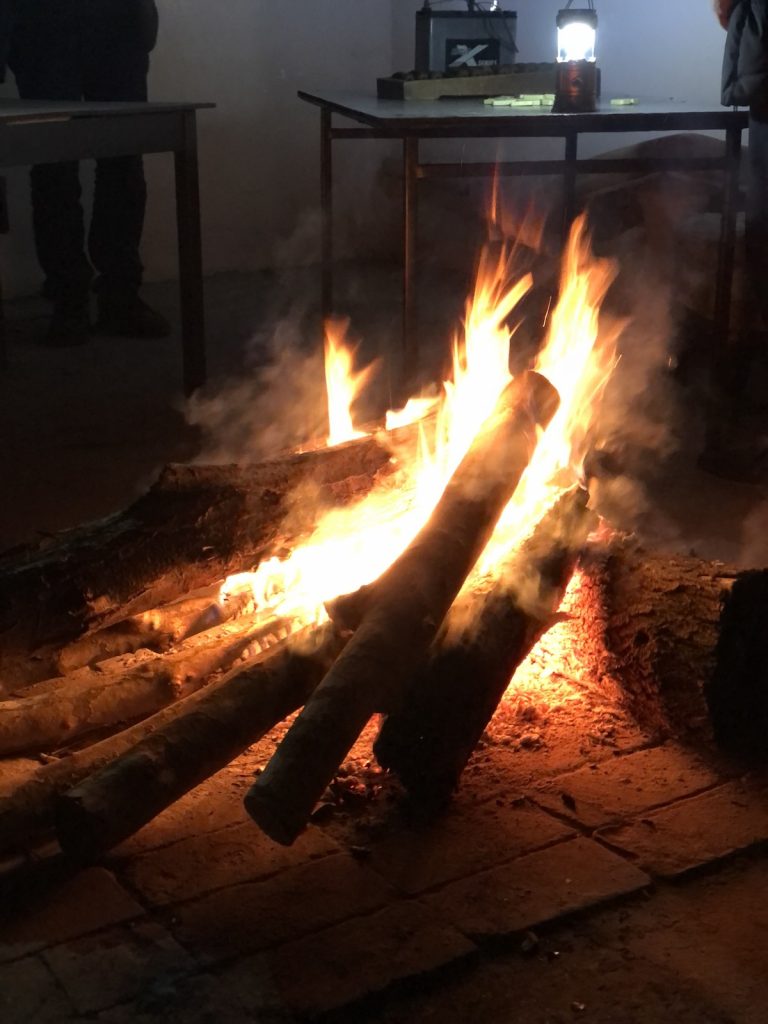

Gatherings in the yard

In one courtyard of the New District, rolling blackouts have become an occasion for meetings with neighbors. Every evening at 5 p.m., residents of a high-rise building on Agrba Street descend into the courtyard, where many years ago, by joint efforts, they built a patskha [Abkhaz. kitchen]..

Everyone brings something tasty from home. Men make a fire, women make coffee. In conversation and gossip, two hours pass unnoticed.

“For two hours we return to childhood, because in this courtyard we grew up together,” says one of the residents of the house, “without phones and social networks, throwing off all our worries, we just sit by the fire. It even resembles something like happiness.”