My Karabakh - Part II: 1988 - The Karabakh protests begin

Armenian journalist and writer Mark Grigoryan describes his experience of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in a series of essays written exclusively for JAMnews.

Karabakh stories, all parts here

1988: the Karabakh protests begin

began for me on 21 February, when I set off with Samvel Shakhmuradyan to the museum of composer Aleksandr Spendiarov.

At the museum, we wanted to find out about the fate of a manuscript written by the composer’s daughter Marina, who described how in 1940 she, a young and talented singer, was shipped off to the gulag, having been accused of making an attempt on Stalin’s life.

But we didn’t make it to the museum. Neither that day nor later. We didn’t get there, because when we met, Shakhmuradyan told me:

“Let’s go to the protests.”

“What protests?” I asked.

“In half an hour there’ll be a demonstration by the opera house, where they’ll speak about how Karabakh has asked to withdraw from Azerbaijan and become a part of Armenia.”

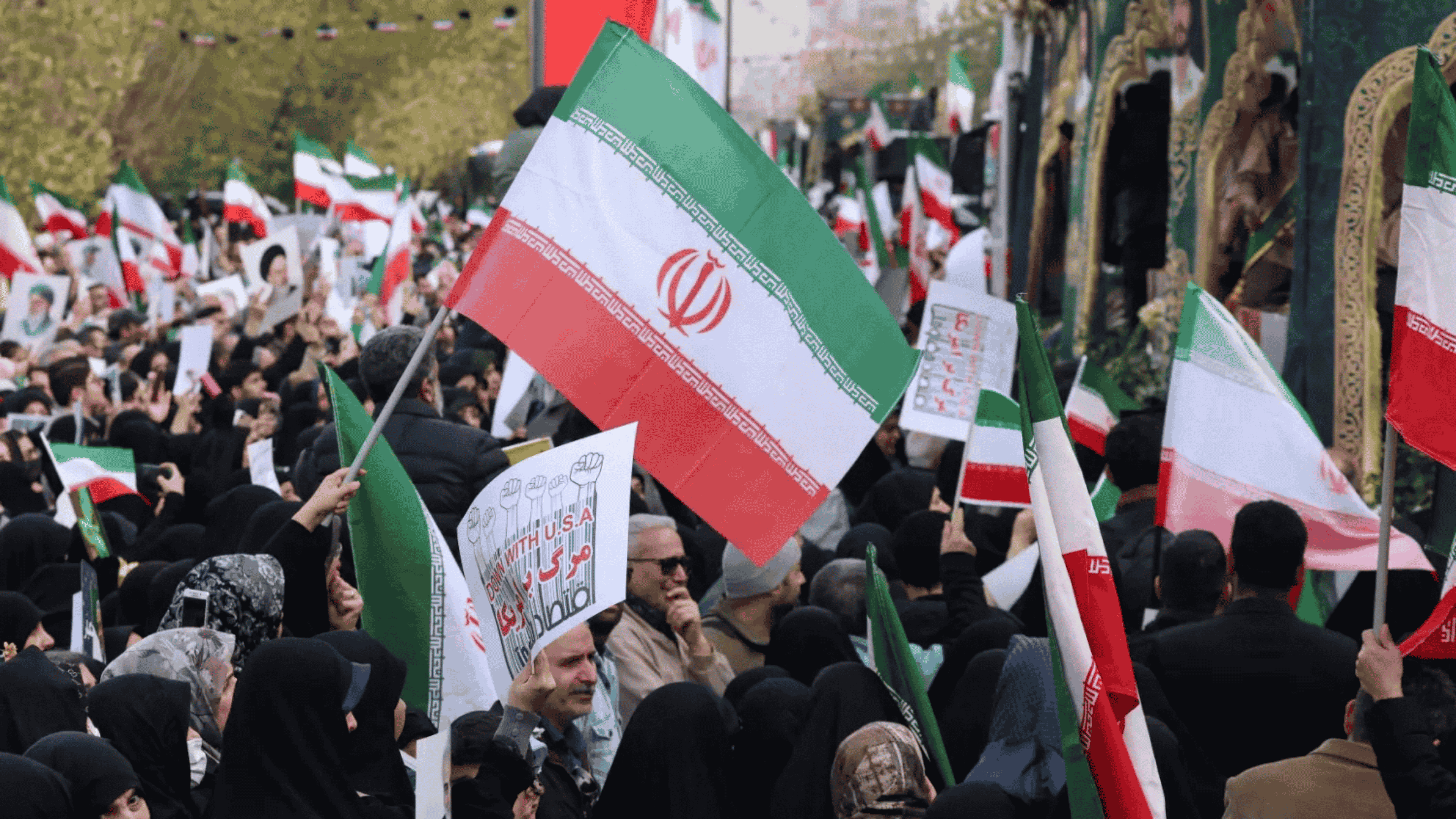

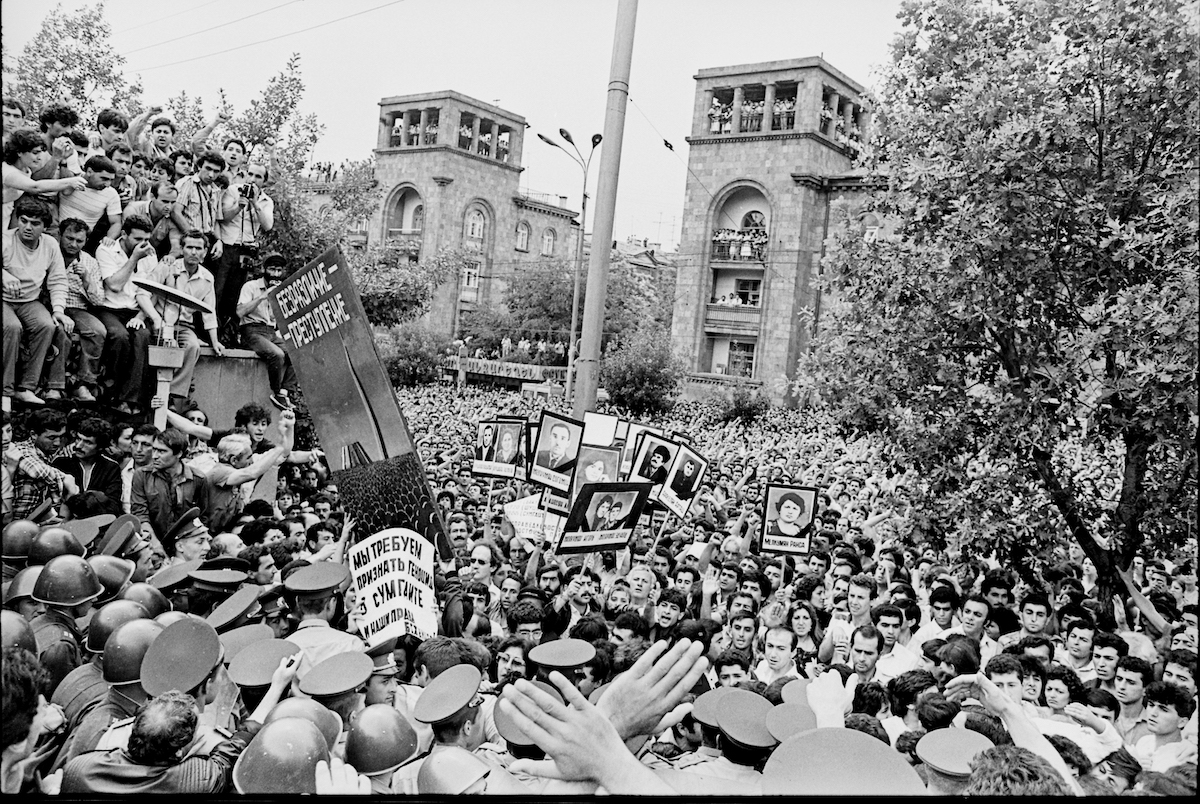

And so we ended up at Opera Square. This was the first in a long line of Karabakh protests, which changed our lives forever and played a decisive role in the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Itall seemed so simple back then: if Karabakh had been given to Azerbaijan by the ill-will of Stalin, then Gorbachev, who had declared the period of perestroykaand glasnost [Rus. restructuring and transparency], had to right one of the biggest mistakes made in the history of the Soviet Union and return the autonomous region of Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, where in all fairness it should have been from the very beginning.

This overly-simplified logic simply had to make its way to the ears of Gorbachev, who needed to hear the historic truth and the problem would be solved.

It seemed that to deliver a fair resolution to the problem would take Gorbachev just several days, or maximum a week.

But pay attention to one important detail: in this logic, there was no place for Azerbaijan, nor for Azerbaijanis. The first Karabakh protests were for Moscow; they were aimed at eliciting a reaction from the centre. And the centre did not take time in reacting.

Vladimir Dolgikh, a member of the Politburo that came to Yerevan, took a look at the masses of several tens of thousands of people (some accounts claim as many as 200 000 people were present) and said that they were ‘a bunch of extremists’.

A few days later, while speaking at a demonstration, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia, Karen Demirchyan, responded to the demand to have Karabakh join Armenia and, not hiding his annoyance, said: “Do you think I have Karabakh tucked away here in my pocket?”

I wasn’t at that particular meeting; I heard Demiryan’s words from Voice of America, because the tumult and emotions of the first demonstrations were so high that my gastric ulcer worsened, and I ended up in hospital. It was there that I heard about the Sumgait pogroms.

This was an enormous shock for me, as it was for many others in Armenia. We were completely unprepared for the idea that our fair demands on the Kremlin could be reacted to in such a way, especially when the reaction did not come from Moscow or Baku, but from an industrial city not far from the Azerbaijani capital.

People talked about terrible events both in their kitchens in Yerevan and at the demonstrations which took place next to the opera almost every day: hundreds of murdered Armenians, thugs roaming the streets, raped girls who were then burnt and who had been stabbed in the stomach. It would seem that we had been sent back to 1915, when the Armenians in the Ottoman empire were targeted simply for being Armenian.

It was wild and disorienting to imagine that Soviet authority, which had seeped into every crack and crevice of everyday life, including into our thoughts, was unable to do anything in order to stop the thugs in Sumgait.

Was it unable or was it unwilling? Had it organised the pogroms itself?

Many were overcome by despair, not knowing what to think. We were in a situation where the only way to find out what was happening in the neighbouring republic was to go to the demonstrations taking place on Opera Square in Yerevan. Rumours were not a negligible source of information. The Soviet press was silent.

But the so-called ‘enemy voices’ of the Voice of America, Radio Liberty and the BBC reported what they could. But they too were rather powerless: the USSR was still capable of preventing foreign correspondents from gaining access to places and events that, if exposed, could cause cracks in the facade of the myth of the unity of the Soviet people, their friendship and brotherhood, and also about the happy life of national minorities.

In those days, I, like many others, all of a sudden felt cut off from the rest of the world: Soviet television was completely silent about the events, only once in a while showing party functionaries of varying levels reading lectures on ‘the brotherhood of nations’.

These lectures gave rise only to anger and frustration. Those who were not involved in the conflict didn’t react in any way. These lectures were not needed by anyone.

Having been released from the hospital, I went to Moscow, where I was doing my PhD. My dissertation was more or less ready, and I just had to complete several small details. I already had a number of articles, all that remained were a few formalities to finish off.

I didn’t pack light for Moscow: I had to deliver a series of pamphlets which explained the ‘only fair position’ on the Karabakh issue.

With time, the Armenian position changed: the cornerstone of the movement was first humanitarian, then political, and then the Karabakh movement became the movement for the independence of Armenia. A few years later, this took on new dimensions entirely, and the war broke out.

But I am purposefully not describing what happened after 1988, because my aim is not to describe the ‘Armenian position’ in the conflict, but to speak about how I, a thirty-year-old man, felt in 1988.

Then, in the spring of 1988, I was convinced: the Karabakh problem was first and foremost a humanitarian issue. The picture looked like this: Armenians had it very difficult in Karabakh. They had it so tough that the population was in rapid decline, many of them preferring to leave, flee and emigrate from their native lands where they had been born and where their ancestors were buried.

Yes, the population of Nagorno-Karabakh declined in the Soviet years (it was the only Soviet oblast in which, untouched by the war, the population had shrunk and not grown).

With time, the number of Armenians became less and less proportionally. In 1925, they had made up about 90 per cent of the oblast, but in 1988 they were down to about 75 per cent.

This caused fears that Karabakh would suffer the same fate as that of Nakhichevan, which had also been settled by Armenians in the beginning of the century, and in which less than 2 000 Armenians remained by 1988, settled in just two villages.

I might be wrong about some of these figures. It’s been more than 30 years after all. But I remember that at the demonstrations, which played an enormous role in the formation of public opinion, they said that the humanitarian situation in Karabakh was not simply ‘bad’, but it was worse for Armenians than it was for Azerbaijanis because this was Baku’s policy: make sure the Armenians disappeared from Karabakh.

But time went on, and I began to notice that my friends and acquaintances all thought something different about what was going on in Karabakh.

But about that next time.

[su_quote]My Karabakh. Part I: Hadrut, a donkey, water and a brawl[/su_quote]