Children born out of wedlock in Azerbaijan

To give birth to a child, one has to go through a hard path: a match-making as is required by traditions, a betrothal, a wedding ceremony, a lavish wedding party, even if it’s through a loan. However, there are mothers who choose a shorter path.

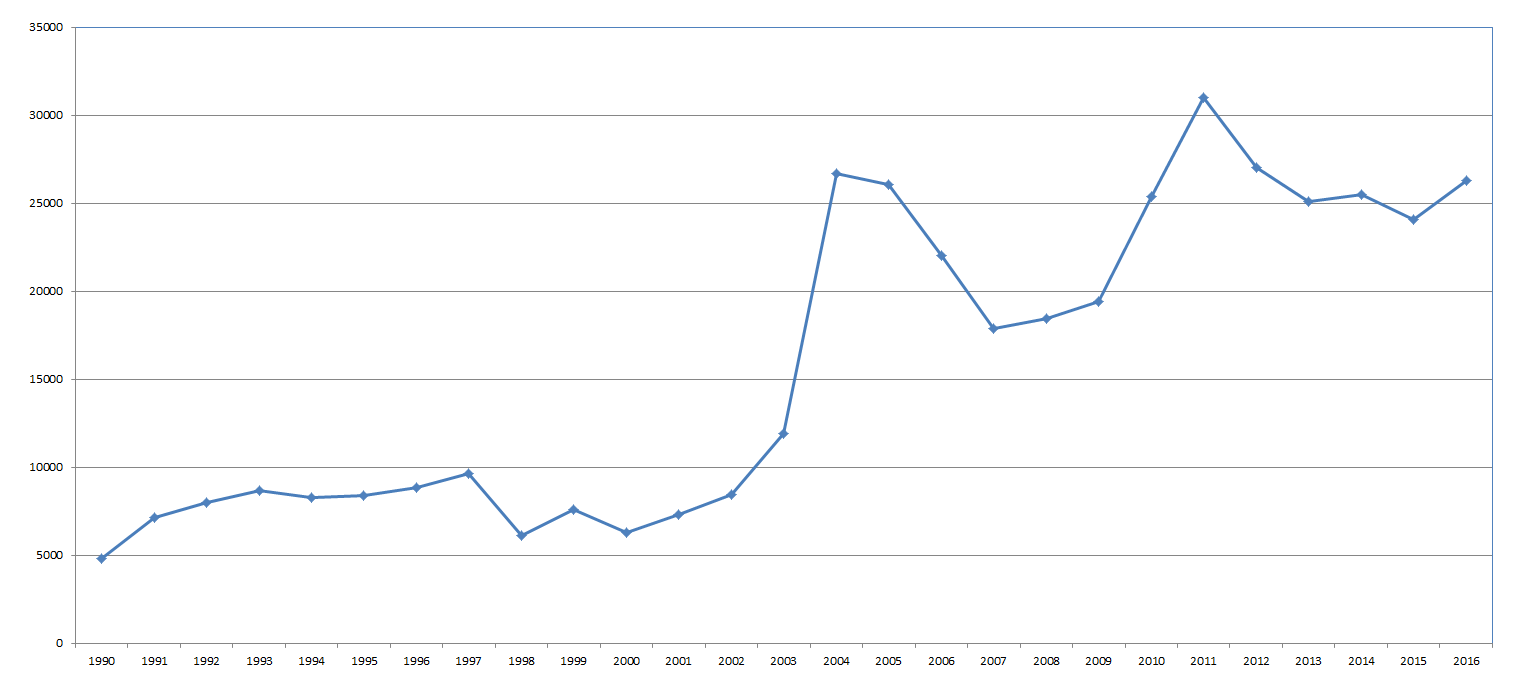

Over 26 000 children were born to unmarried mothers in Azerbaijan in 2016.

Out-of-wedlock birth rate in Azerbaijan (according to the State Statistical Committee data)

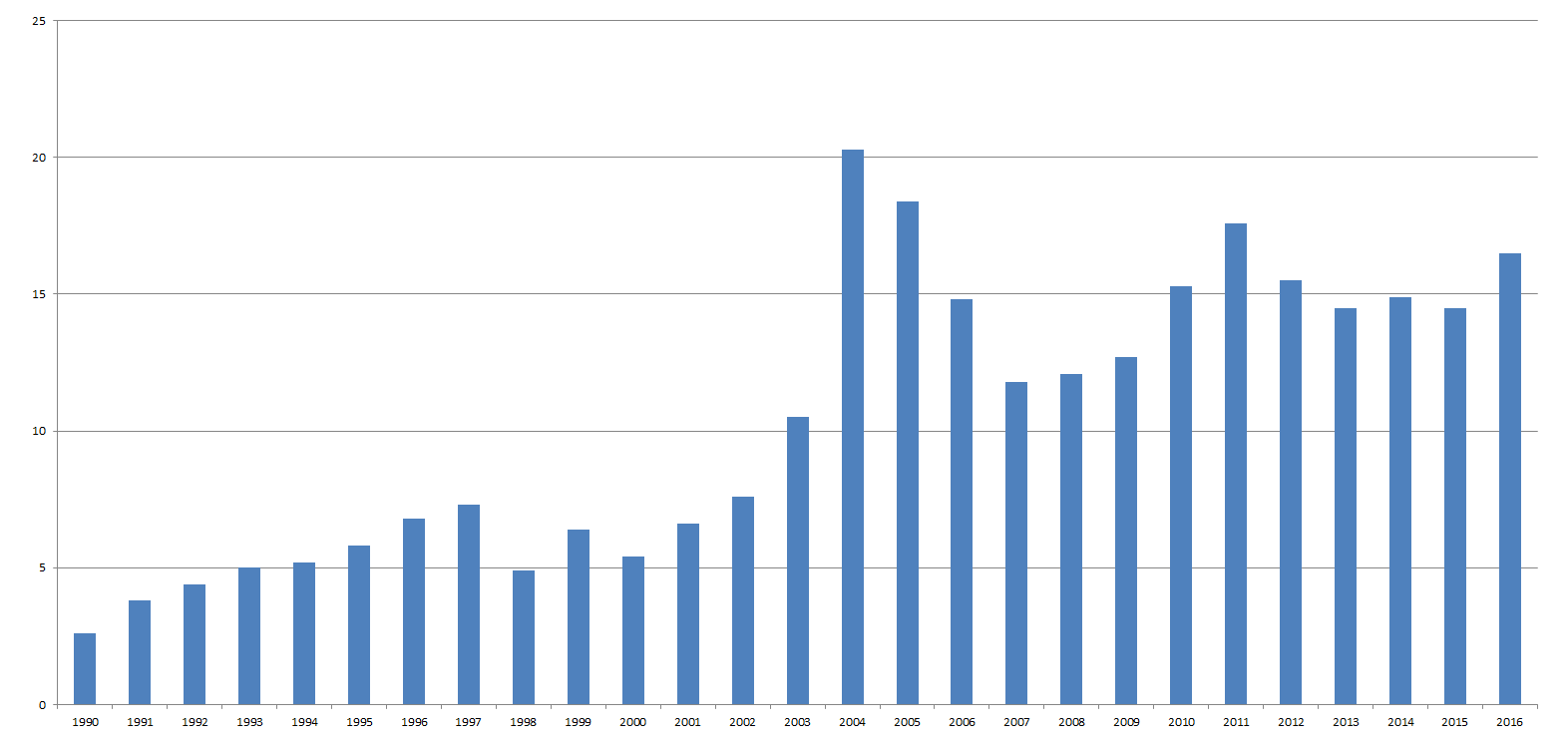

Ratio of children born out-of-wedlock to the total number of births (according to the State Statistical Committee data) in percentage

We’ll try to figure out what’s behind these numbers.

Zenfira

Zenfira Agayeva*, 30, has three children. As you listen to her story, you feel as if you are watching a movie. She has a beautiful face. Although she is wiping her tears from time to time, she doesn’t look unhappy. Maybe that’s because she is accustomed to the emotional stresses.

During the conversation, she occasionally admonishes her children who are playing outside, but she does it in a calm tone.

Her first child was born when she was 17. She ran away and lived in a common-law marriage with a man, who was 15 years older than her. The man dumped her when she was 7-months pregnant. But he returned after the baby was born. They lived together for one year and then he disappeared never to come back again.

When she started searching for him, she found out that he was married. The father didn’t acknowledge the child, so the latter now bears his mother’s family name.

Then Zenfira met another man. When he learned about her past, he said he accepted it. Having entrusted her first child to her mother’s care, Zenfira started a new relationship. This relationship wasn’t registered officially either. The guy’s mother, who had learned about the girl’s past, was flatly against their legal marriage.

Zenfira gave birth to two sons, one after the other. Although they lived like a family, they never officially registered their marriage. They got the children’s birth certificates several years later, when the children were supposed to go to school. The father gave the children his surname.

“He treated me and the children well. His mother didn’t want us to get married legally. So, every time, he had to come up with some new reasons for not doing it. I tolerated it, because he supported us. My first child rarely visited our place. So, I had to go to my mother to see him. However, after we built a new house and moved there, the situation changed. He started beating me and he didn’t take care of the children.

“Then my mother died and my brother sent my elder son to the orphanage. They refuse to tell me where he is. I haven’t seen him for 2 years already. My family has also rejected me.

“Once, my husband severely beat me, because I’d bought halva in the shop. I took the children and went to the shelter. It’s the second time I’m staying here.”

Now Zenfira is looking for her elder child, while thinking about the other two children’s future. She doesn’t require an official marriage. The only thing she wants is to return home. She can’t provide for her children herself.

The family’s refusal to accept her back is a separate story. When she returned to her parental house for the first time, she was 9-months pregnant. It was then that her brother, a 9th grade student, committed suicide. Now the family blames Zenfira for that, claiming that their son allegedly committed suicide because his sister got pregnant by a married man.

What does the law say?

Under the Family Code, after a child is born, the paternity is established. A biological father’s name is recorded on a child’s birth certificate and a child gets certain rights. The birth certificate is issued by a relevant public agency, on the basis of the document, issued to a mother at the maternity house upon a child’s birth. In case of a legal marriage, a woman just names her husband’s surname and gets all the documents without any problems.

If the parents aren’t married officially, they should file an application with the executive authorities. If paternity is established, a child will enjoy the same rights, let’s say, to an inheritance or alimony, as children born to legally married parents.

If a father doesn’t accept a child, the latter either stays under the mother’s care, or a lawsuit is filed to establish paternity.

What do neighbors say?

For a patriarchal Azerbaijani community, the birth of an illegitimate child in the family is not just undesirable, but it’s absolutely unacceptable. Not only does a woman lose any chance to marry again and is subjected to public condemnation for the rest of her life, but the child also gets an offensive nickname ‘Bijbala’ (‘a stray child’, a vulgar mocking name – ed.). Therefore, few women decide to give birth to a child out of wedlock. And you will rarely find a woman who makes the deliberate decision to give birth to a child ‘for herself’, to raise and bring up a child on her own.

If you take a look at the statistics, you’ll get the impression that over 26 000 women in Azerbaijan have decided to become single mums. Is it really so?

What do officials say?

According to Aynur Veysalova, a senior consultant at the Department of Information and Analytical Research of the State Committee for Family, Women and Children Affairs, the children born out of wedlock are divided into two groups: “The first group comprises children born to couples who started a family, but who didn’t register their relations on paper. There are quite normal relations in those families and fathers don’t give up on their children.

“The second group includes children, born to couples who break up after living together for a while. Children in such families experience psychological problems. There are also some financial problems – only a mother’s income is hardly enough to provide for a child.”

And that’s another problem; according to Veysalova, there are about 9 000 single mothers in Azerbaijan and they are often unable to provide for themselves and their children. What prevents them from getting education and finding jobs is the patriarchal lifestyle, which is commonplace in many families. Women in such families are financially dependent on their fathers or husbands all their lives.

Speaking about the influence of free relations, as a ‘stylish’ trend, on the growth of out-of-wedlock births rate, the committee official compared Azerbaijan with Europe: “Europe prefers unofficial relations, but, at the same time, no one in Europe renounces responsibility for cohabitation; the laws there are rather stringent. Whereas in Azerbaijan, the free relations couldn’t replace the family model. Mostly uneducated and uninformed couples show interest in such relations in our country.”

So far, the committee sees a solution to this problem in carrying out awareness-raising activities and in introducing punishment for mullahs, who conclude religious marriages (‘nikah’) without official ones. Certain progress has already been made in this regard. Mubariz Qurbanli, the Chair of the State Committee for Work with Religious Organizations of Azerbaijan, has recently pledged that the clergymen, acting in circumvention of the state, would be strictly punished.

Divorce without marriage

Many people in Azerbaijan believe that an increased divorce rate is one of the reasons for refusal to officially register the relationship. In other words, when divorce stopped being something extraordinary, the grooms’ relatives have started apprehending possible division of property in advance. If a marriage isn’t registered officially, then there is no problem.

For example, Leyla Safarova*, a mother of two children who has been staying in the shelter for quite long, says that in her case everything was done in according with the traditions, be it match-making, betrothal or wedding ceremony. But they were still denied to officially register their marriage. “We were told that the groom had some document-related problems and we were asked to wait. I got pregnant two months after the wedding. My mother-in-law openly stated that we wouldn’t get married officially, so that I wouldn’t lay claims for a share in the apartment in case of divorce.

“We got divorced 11 years later. My children bear their father’s surname, but I didn’t get anything after the divorce. The only thing I managed to achieve through court was the alimony for my children, that’s it.”

Early marriage and dual life

Mehriban Zeynalova, the Chairperson of ‘Təmiz Dünya’ (‘Clean World’) public union:

“Early marriages are one of the reasons for such a high rate of children born out of wedlock. Girls are married off before they reach the age of consent and the children are registered as born out of wedlock. For example, in 2015, 6 370 children were born to unmarried females aged 15-19. A person cannot legally get married at the age of 15.

“Another reason is a dual life, that is, a man has an official family, but he has an affair with another woman, and a child is born of this ‘parallel’ marriage.

“The third group includes couples who don’t register their relationship when starting a family.”

Sevda

Our second character is ‘a victim’ of a man with a dual life, though she herself doesn’t like that word.

Some 30 years ago, Sevda Azizova* moved to Baku from a region with a conservative lifestyle and visions of relations between men and women. Her father worked as an engineer at a water service company, while her mother was a teacher.

“I moved to Baku after finishing school. I enrolled in the medical institute here. Then I met a very handsome man. He was 26, and I was just 19. According to him, he was the only child in the family and his parents were rather well-off.

“What’s the point of complaining now that he cheated me? It turned out that he was engaged. When he found out that I was pregnant, he said that his parents would kill him, because he was engaged to the daughter of his academic supervisor. He was going to build a career in science.

“The situation was different at that time. Young people didn’t know much, as compared with the present-day youth. I was afraid to tell my parents about it. My landlady could have advised something, but she learned about it when I was already 7-months pregnant. I couldn’t have an abortion.

“When my father learned about it, he said he didn’t want to become a child killer, adding that I’d better keep out of his sight.

“My mother secretly helped me. And also, my landlady, a Russian woman, took much care of me until the last day of her life.”

Sevda khanum gave birth to a son. She raised him and provided him with an education. She has never visited her native region again and she has completely lost her family links after her mother’s death. She found it very hard to do everything on her own:

“The laws were very stringent at that time. A neighborhood police officer demanded on a number of occasions that I should name the child’s father, saying otherwise he would have to institute criminal proceedings into a rape case. However, my landlady knew the laws. So, she interfered in the matter, saying that no one was entitled to look for a child’s father against my will.

“I gave my family name to my son. Only God, my landlady and I know what I’ve been through.

“Then I graduated from the institution. Work placement was the thing that I feared most. I was afraid that I would be dispatched to a region with my fatherless child. But then the Soviet Union collapsed and the work placement practice was abolished. So, I stayed in Baku.

“Being a pediatrician, I used to work in a bakery. Who would have employed me without a bribe at that time? Whereas in the bakery, we were allotted bread and buns. We left the bread to ourselves and sold the buns.”

Sevda khanum’s son graduated from the Azerbaijani Technical University and left for Russia to work: “However, work is not the only reason he left. When a university student, he fell in love with a girl, his group-mate. And she loved him too. When I went to her family to arrange a match, her parents refused to give their consent, because they learned that the guy didn’t have a father. My son was very frustrated and he left.

“He started earning money, we bought a land plot and built a small house. He met an Uzbek girl there. He got married. He has two children now. We often visit each other. I don’t work anymore, my son provides for me.”

During the conversation, Sevda khanum didn’t say a single unkind word about the man who’d left her. ‘It’s my fate’, she insisted. She never got married again, though there were men who proposed to her:

“There was a man, who told me he would marry me only if I send my child to an orphanage. And I kicked him away! There were men who offered to ‘support’ me, but I refused. Sometimes, people were talking crap behind my back. Sometimes I laughed at the women, who gripped like a vice on their husbands on seeing me. As if I was going to take their husbands away from them.

“There were days when my son and I ate only bread from the bakery. But I raised my child myself. I’m grateful to him, for he never asked me anything. I told him everything when he enrolled in the university. I told him: ‘If you want to find your father, I can tell you his name.’ But he didn’t want it.”

A question that a young bride is most frequently asked after the wedding is as follows: ‘Is there something?’ And that ‘something’ implies a baby, a child, who usually comes into an Azerbaijani family unplanned, but with documents. It’s a real tragedy for the Azerbaijanis if that ‘something’ appears without an engagement and wedding, and the statistics could hardly change it.

*names have been changed to protect the privacy of the individual.