One year after emigration: Russians in Georgia

Russians in Georgia

More than a year has passed since a mass influx of Russian citizens to Georgia who left their country in protest of the war in Ukraine. In September they were joined by a new wave of compatriots, thousands of Russians seeking to avoid mobilization. According to various sources, more than 100,000 Russian citizens now live in Georgia.

On the streets Georgian cities such as Tbilisi and Batumi, Russian speech is heard at every step. Russian citizens have started a new life here — they work, study, raise children, go shopping, rent apartments, get together, walk in parks. Russian cafes, shops and the like have sprung up. In numerous Russian-speaking groups on social networks people offer each other a variety of household services — cleaning, haircuts, manicures, language lessons, plumbing repairs.

One gets the impression that a parallel world has arisen in the country, which often does not intersect with the local one at all.

One February evening in 2023 about 30 people gathered in a small office on Tara Shevchenko Street in Tbilisi.

They introduce themselves as Katya, a chemistry teacher; Yuri, dancer; Lena, psychologist; Anastasia, banker; Gleb, programmer; Stas, photographer; Nikolay, musician; Christina, English teacher; Nadia, marketer; Ivan, business consultant; Ivan, bartender; and Alice, beautician

With rare exceptions, most of them are from Russia.

Their meeting place is called Reformum Space. This is a space for discussions, meetings and presentations, recently opened by the international organization Free Russia Foundation, where representatives of the Russian-speaking community living in Georgia gather.

This time, Nikolay Levshits meets Russian-speaking immigrants – he came to Georgia from Moscow in 2019 and has become a real connoisseur of local life. He has the largest Russian-language Telegram channel in Georgia with about 95,000 subscribers.

After the start of the war, the channel became almost vital for many Russian emigrants — there they look for work, find out how to open a bank account, where to duplicate house keys, which school to send their children to, where to go to yoga, and much more.

- “If they close the border, there will be only one way left – war.” Stories of refugees from Russia

- “The letter Z is on every third car” – how a Russian traveled from Moscow to Tbilisi

- The fate of Ukrainian refugees in Georgia after they fled the war-torn areas via Russia

The purpose of this meeting is for people to get to know each other, share their needs and discuss solutions.

Those sitting in the hall stand up one by one and tell their story — when they arrived, what their profession is, what worries them, how they live in Tbilisi, what plans they have.

For example, a cosmetologist from Moscow plans to open a beauty salon, a psychologist from St. Petersburg offers his services to the Russian-speaking community, a young chemistry teacher and a partner cannot find a job in Gori, a bartender invites everyone to Abashidze Street.

Mark, start-up guru

One of the speakers is 34-year-old Mark Markin. He talks about his startups. Last year on March 22 Mark came to Tbilisi with his wife Kristina and 11-year-old son Stepan.

Mark is originally from Ulyanovsk, but had been living in Moscow for many years. In 2009 he worked as a dispatcher at the Moscow Vnukovo airport, and a year before the war he launched a small online sales business.

On February 24, 2022, his life was turned upside down.

“Before the war, I expressed my protest against Russian policy in every possible way. And on the 24th, the question arose with an edge — either you stay with them, or you leave.

Mark left his job and his small business.

“I knew that Georgia is a free, democratic country that has defeated corruption and bureaucracy and is on its way to the West. I had always had a very good idea of Georgia, which is why I decided to come here. But I was also scared, I didn’t know how we would be welcomed.”

It happened that the very first Georgian he met at the Tbilisi airport has now become his best friend. This is Givi, a taxi driver who helps Mark solve various problems:

“While earlier I called my father in Moscow and asked for help, now at such moments I call Givi. Givi has all the tools, Givi knows the way out of any situation. Once he even brought us to Sighnaghi.”

Mark rented an apartment for $350 in a new residential complex on the outskirts of Tbilisi.

“Then prices were low. Now, as far as I know, it costs twice as much. This is a very nice big apartment. People from all over live in this district.”

- How the war in Ukraine affects the real estate market in Georgia

- “It’s like the war has started again.” What do Russians living in Georgia think about mobilization?

Mark is in business again — transportation from Georgia to Russia and back. Mark’s office, which opened on January 23, is a branch of the CDEK company.

“We can send goods from anywhere in Georgia to any part of Russia. Our services are very cheap. For example, sending a small parcel from Georgia to Novosibirsk costs only 27 lari [about $10].”

Mark and Christina work hard and have little time for fun. Mark likes to walk along Chavchavadze Avenue in the center of Tbilisi. On weekends they go to the movies.

Eleven year old Stepan has started learning English in an international class at a Georgian-American school. There are twelve students in his class, four of whom are from Russia, the rest from Egypt, China, and Vietnam.

“He has a very good relationship with other children and he likes it here, although he often asks me when we walk down the street and he sees various inscriptions about Russians on the walls: ‘Dad, why are they writing about us like that, what have we done?’ I explain what we have done, that these are well-deserved words and must be endured.

I’m ashamed. I can’t say anything. I cannot change my government and the only thing I could do was leave Russia and try to give my son a better future. If I had stayed there, they would have put me in jail and I would not have been able to help my country or my family. Here I can at least write on the wall: Russia, fuck off from Ukraine and Georgia.”

Russians in Georgia

Katerina, activist

Katerina Kiltau, 30, was declared a foreign agent in Russia in 2021 due to her opposition activities. War or no war, she wanted out of Russia.

On March 5, Katerina came to Tbilisi on a mission to help the Ukrainians. Together with friends she created the Emigration For Action group, which helps Ukrainian refugees and has become a meeting place for the Russian-speaking community.

Lectures, anti-war festivals, discussions and various educational events about Russian politics and propaganda take place in a narrow Bethlehem street in Old Tbilisi.

“We work every day, so we feel and remember that every day is a war. Every day, every minute, we feel responsible for the people we help.”

The events are attended mainly by Russians.

Several times they also had Georgian-speaking guests, but according to Katerina, it is quite difficult to find such people and it is almost impossible to get Georgians interested in attending their events.

“We know how much harm Russia has brought to Georgia, and so we understand why Georgians do not want Russians here. We are clearly in our own bubble, we are afraid to communicate with Georgians and do little to integrate. However, it is necessary to have dialogue and work together on projects to achieve a common goal.”

Katerina is lucky; she rents an apartment in the center of Tbilisi for only 600 lari [about $233].

“This is an old Tbilisi house and I love it very much, but I feel a great responsibility for all those students who can no longer find an apartment because of us.”

“Despite the complex Georgian-Russian context, Georgian hospitality is truly unique. I have not experienced a single case of aggression. On the contrary, everyone is trying to help.”

Also unique is the fact that almost everyone here speaks multiple languages. In Russia, for example, this is a rarity. Now I understand how many imperialist pretensions we have.”

She is, however, planning to go to Germany.

“I am planning to go to Germany and look around. Hopefully I will be there in the next six months. I want to scale up the project so I can help more people and let more people know that not all Russians are bad.”

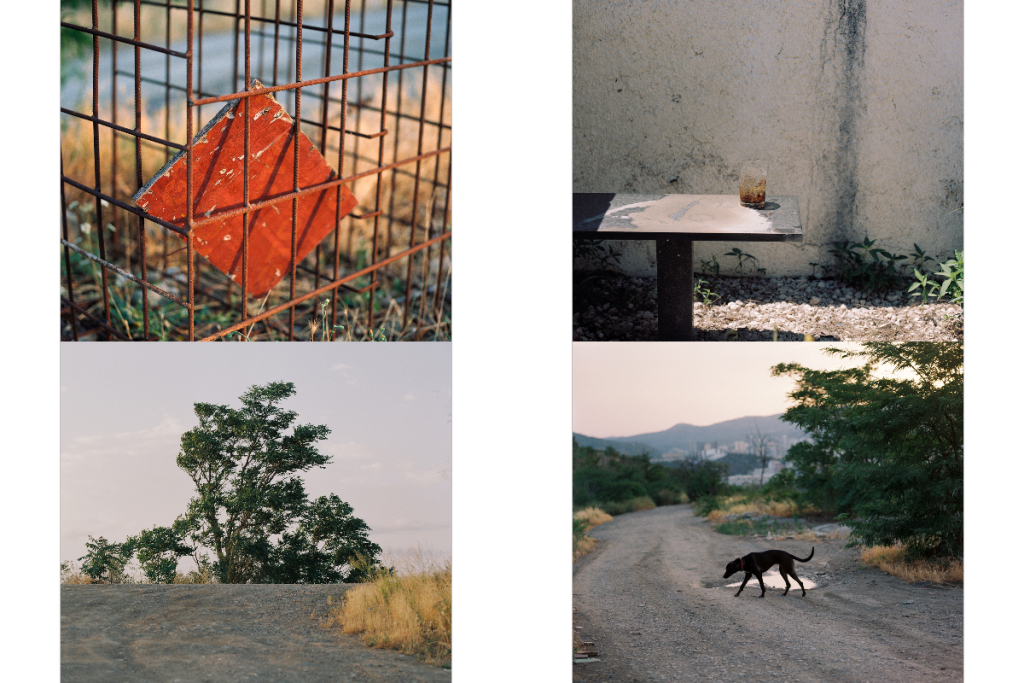

Egor, photographer

Egor, 34, came to Georgia with his girlfriend right after the start of the war. They lived with friends until finding their own place.

“We liked it from the very beginning. This is an old, completely wooden apartment. We went to see it right away, and when we checked it out that evening, it already had 700 views.”

Egor Slezyak is a photographer. In Moscow he had many orders: portraits, advertising, food, interiors. In Tbilisi, it is very difficult for him to find a job.

“I have done several commissions for a Dutch newspaper, once I made a video for the National Gallery, that’s all. I understand that the photography market in Georgia is very small and even Georgians find it difficult to find a job.”

He’s been back to Moscow several times.

“I have no income here. I was offered a small job in Moscow and I could not refuse, so I went. It was a very strange feeling. When you leave your country because you are completely alienated from what is happening there, and then come back to receive money, this is a very unpleasant compromise.”

Egor’s girlfriend Danin is also an artist — she creates modern installations from old tapestries. Her work is also hard to sell.

“When you have no income, everything is expensive. Vegetables and dairy products in Tbilisi can be bought very cheaply, but in general, prices in Tbilisi and Moscow are about the same.”

For the first three months, Yegor and Danin did not actually leave the house, as they were not in the mood to have fun. Even now, they spend most of their time at home or visiting friends, mostly otherimmigrants.

“When you walk around the city and see Ukrainian flags everywhere, you remember every minute that there is a war going on, and it is impossible to feel good. Those who remained in Russia probably try not to notice what is happening and continue their daily lives. And I always remember what my country is doing and that I am Russian.

I always feel like no one is happy that I’m here. I know that the Georgians are waiting for us to leave. This is very annoying, but understandable. So we have no other choice but to adapt.”

Russians in Georgia

Who has come to Georgia?

There are no exact statistics on how many Russian citizens have come to Georgia after February 24, 2022.

According to border crossing data, from March to November 2022, over one million Russian citizens crossed the Georgian border.

According to the latest data published by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, there are currently about 113,000 Russian citizens in Georgia.

The wave of migration from Russia is divided into two parts: “February” and “September”.

Twenty year old Katya Chigaleichik is a social anthropologist who is engaged in research, and after moving to Tbilisi, she began to study the topic of the migration of Russian citizens to Armenia and Georgia as part of the Exodus-22 project.

According to her, the majority of people who came to Georgia from Russia are mostly young people born in 1980-90 who have a higher education and profession. Most of them are from St. Petersburg and Moscow.

There is an opinion that the second wave of emigrants who arrived after “September”, i.e. after the announcement of partial mobilization in Russia, are mainly people from the regions. However, according to Katya, this is not the case, and most of the second wave are Russian citizens who came from big cities.

According to Katya, 50% of immigrants from Russia in Georgia are programmers and IT specialists. This is the largest group with remote work and relatively high salaries. They live in Georgia as tourists — they travel to different places, see the sights.

“They are for the most part introverted and less involved in everyday life in Georgia.”

The second group is creative people. Musicians, designers, artists, who lost everything in Russia and are now in a hopeless situation, are looking for work and are forced to start life from scratch.

The third group is people who started a business here and their financial situation is relatively better than the rest.

The fourth group is the “September” immigrants who were engaged in physical labor in their homeland and are now looking for the same job in Georgia.

Anastasia Burakova, 30, who helps political emigrants from Russia as part of the Ark project, also deals with the migration of Russian citizens.

“The first wave of emigrants are mainly those who opposed Russian policy, participated in opposition speeches and simply could not stay in Russia after the start of the war. The second wave, which came after the announcement of partial mobilization, is more diverse. However, to a large extent, these people are also political emigrants.”

According to Anastasia, at this stage there are about 2,500 activists and political emigrants with Russian passports in Georgia.

Coexistence of Georgians and Russians?

Georgians and Russians have been living under the same sky for more than a year, although their relationship is rather complicated.

The Russian citizens we spoke to said they knew a few rules had to be followed in Georgia.

For example, the first rule is not to address young people in Russian.

“In general, you should stay away from them. They don’t like our presence here,” Gleb, 21, who rents an apartment in Tbilisi with three friends, says. They are programmers from St. Petersburg who arrived in Tbilisi in April 2022.

On the other hand, as we were told, it is very easy for Russian citizens to communicate with people over 50-60 years old — they are more friendly and have nothing against communicating in Russian.

“I start to speak only English, I never speak Russian. But in many cases, the vegetable seller or the taxi driver speaks Russian to me,” photographer Egor says.

“Communication is sometimes very funny, before we decide what language to speak,” Katerina Kiltau says. “I always say the first few words in Georgian, then I continue in English, then people understand that I am Russian-speaking, and, if they know Russian, then they themselves begin to speak it. Sometimes we speak several languages at the same time.”

Despite this, everyone agrees that communication between the local population and the Russians at the moment does not go beyond one-time contacts.

“Georgians are very polite and friendly people,” Katya Chigaleichik says, “so they try their best not to show how tired they are. We came to them from a hostile country, we brought too many new problems, and they are just waiting for us to leave. No one tells us this directly, but we know it and feel it.”

22-year-old Artyom, a friend of Gleb, says that they only communicate with the owner of the apartment, or with people who work in a store and cafe. They have not made friends with anyone in Tbilisi:

“We try not to catch the eye of people here. We are clearly not liked here. We understand this, but we have no choice. I admit that my generation knew little about Georgians. Older people have memories of contacts with each other during the Soviet era, but we do not. This place is alien to us, just as we are aliens to Georgian youth,” Artem says.

In Telegram chats, which are mainly created by migrants, you can read various reviews about life in Georgia.

The Georgian climate and food are especially praised. They are surprised that Georgians speak loudly, the level of their involvement in politics, and also the fact that they do not take off their shoes at a party. As for prices, many write that prices in Georgia are already comparable to those in Moscow.

“Yes, there are many differences between Georgians and Russians at the level of everyday culture. It is especially noticeable that the streets are full of dog shit, I don’t know how or why you endure this,” says Artem.

Locals interviewed by JAMnews are ambivalent about the presence of so many Russians.

Part of the population believes that Russian migrants will revive the country’s economy. Others see the danger given the occupation of Georgian territories and the historical context.

The majority of those interviewed by JAMnews say that although they constantly hear Russian spoken on the street, they have either never or rarely had personal contact with Russians.

Tata Amashukeli has small children and every day she brings them for a walk in the park.

“There are a lot of Russians on the playground, also with children, we meet every day. We smile at each other as a sign of greeting, but there is no other communication. They never express a desire to make contact. They talk to each other, very quietly. One day a girl was asking someone on the phone where she could buy winter overalls for a child. Although there were local mothers nearby, and she could have asked us, she did not consider it necessary,” Tata says.

43-year-old Tamara sees the problem not specifically in a person of Russian nationality, but in a large number of Russian citizens:

“In fact, the national composition is changing in Georgia. I live in the central district of Tbilisi, and every second person on the street is Russian. In no way do I want you to get the impression that I am separating people by nationality. This is fascism. I just think that it is not we, the citizens, who should think about it, but the government – to introduce a visa policy or some kind of control. Otherwise it isn’t dissidents, just people who don’t want to get shot.”

According to an opinion poll conducted by NDI and published in February 2023, 69% of Georgians believe that the number of Russians could have a negative impact on the country, while only 17% believe it could have a positive impact.

There is an instinctive among Georgians that is groundless, says Paata Zakareishvili, political scientist and former Georgian State Minister for Reconciliation and Civil Equality, belueves:

“Georgians fear that the Russians have come with evil intentions and that in the future Putin will use their presence in Georgia against us. Putin does not need to send tens of thousands of Russian citizens to Georgia and then attack us. Moreover, he does not need a reason for this at all. He can blow something up in Tskhinvali and blame the Georgians, it would not be hard for him.”

In his opinion, the fear that Russians will compete with Georgians in the local market in business is much more realistic:

“They are more prepared than Georgians in many areas, and it is quite easy for them to get a job. Moreover, in some cases the quality of service has also improved. For example, I heard that a Russian repaired a computer more efficiently and better than a Georgian. They are more qualified and competitive, and this may give rise to fear that they will take the place of Georgians.”

Katya Chigaleichik, who studies Russian migrants in Georgia and Armenia, agrees that contacts between the Russian community and the local population were minimal this year. According to her, Georgia differs from Armenia, inasmuch as occupation is a factor:

“Many Russians think that being too active on their part will irritate the Georgians, saying that for them we are all occupiers, it’s better to be by ourselves and not be too active.”

According to Katya, the Russian community is generally very closed and often does not go beyond its surroundings. In Tbilisi there are so-called “Russian” places where only the Russian-speaking community gathers. Such, for example, is Koshini bar, which offers a view of Old Tbilisi.

“Basically, we communicate only with each other and mostly do not communicate with Georgians. In most cases, we have the same friends here with whom we were friends in Russia. The circle of people around us has not changed much.”

“Russian” places where there are no Georgians

Koshini Bar was opened by 29-year-old Artem Grinevich in May 2022 with the aim of creating a multicultural space for people of different countries to socialize and their integration into Georgian society. But it never materialized — most of the bar’s visitors are Russians.

The bar organizes concerts, film screenings, karaoke, discussions, theater performances. Despite Artyom’s wishes, Georgians don’t go to his bar.

“It is absolutely clear why the Russians in this country are not trusted and they avoid relations with us. We had several events that Georgians came to, but there were not many of them. Finding a local person who will come here and participate in any event is almost impossible.”

Russians in Georgia

Artem tried to hire Georgian staff, even offering them a higher salary, but no one responded.

“We feel very responsible for making everything so expensive. So we really want to have Georgian employees and pay them more. Everyone treats us very politely, but no one wants to come into contact with us.”

Koshini is another popular meeting place for the Russian community, with about 500 regulars.

Grail, Chacha Time and Ploho Bar are also considered “Russian” establishments. In addition to entertainment spaces, there are many places for social and political meetings: Dom, Reforum Space, Antizona, etc. There are many places for cultural events in the Vera district in the center of Tbilisi –Auditorium bookstore, Kera Space, Dissident Books, Bumaga, and so on.

What’s going on outside of Tbilisi?

Denis Kuznetsov, 26, came to Georgia after the announcement of partial mobilization in the fall of 2022.

He settled in Batumi because it is much easier for him to communicate there.

“I couldn’t find a job in Tbilisi. You have to speak Georgian there, and in general, people who speak Russian are not treated very well. I was afraid to say something in Russian, I had to speak in English. Here it is easier to speak Russian. It is easier for me to find a job in Batumi and I feel better here.”

In Russia Denis was an actor, now he works in a Batumi bar. His salary is 800 lari [about $310], but in the case of generous patrons, he can earn 1,800 lari [about $700] a month.

Due to a busy schedule and low income, Denis cannot travel.

“I would be happy to have a remote job like others and see Georgia: beautiful nature, good people, warm climate. This is the ideal country if you have money, but I can’t afford it. On working days they feed me, and on other days I have to feed myself, pay the rent — it’s not easy. I can’t even afford a laptop.”

Denis made friends with Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian emigrants in Batumi. They get together and play board games. Sometimes Georgians also join. In the evenings he walks along the beach.

He does not even think about returning to Russia. “I’ve had high blood pressure for a week to analyze what my country is doing.”

Denis plans to travel to Germany and hopes to be there in May.

What happens next?

For many Russians, Georgia is a kind of transit space where they consider their future plans after a hasty flight from Russia.

But there are those who intend to stay in Georgia.

According to Katya Chilageychik, there will soon be more of them, because the Schengen zone is closed to Russians and Kazakhstan and Turkey have tightened their regulations:

“More people will come and stay here, so we need to start building relationships with the locals. To do this, first of all, Russian immigrants must have a good understanding of where they are. Today everyone already knows what needs to be done to be a “good Russian”: one must say that 20% of Georgia is occupied by Russia, one must say “hello” and “I am against the war.” These phrases have become a kind of calling card. Everyone has already learned them, but in many cases people have no idea what these phrases really mean and what the history of Georgian-Russian relations is.”

“The Russians know that Georgia is occupied by Russia, and this topic is very painful for Georgian society. However, in addition to this knowledge, Russian citizens often do not know how to behave, and this causes even more irritation,” Anastasia Burakova, founder of the Ark, says.

In turn, activists are trying to fill the gaps with lectures and trainings.

For example, in clubs, Russian immigrants are told the history of Georgian-Russian relations and explained why their presence in Georgia may be unpleasant to locals.

These types of meetings take place at the Koshini bar, Emigration For Action office, Reformum Space, and other venues.

“During mobilization, a lot of Russians who came here had no idea about the occupation,” Artem Grinevich, founder of Koshini bar, says.

“They were surprised to feel a strange attitude. We organized a special event for them and explained what was going on. We talked about Abkhazia, South Ossetia, the 2008 war and the occupation. We also let them know how much trouble we have caused the Georgians, even in terms of raising prices.”

Katya Chilageichik also organized several private events where Georgian and Russian people from different fields met.

“We met with Georgian and Russian journalists, feminists, activists of the LGBT community. Such meetings are necessary to exchange experience, knowledge and problems with each other. However, the meetings were held in complete secrecy, and we did not publish anything on social networks.”

According to activists, on the one hand Russian emigrants should overcome their fear of relations with Georgians, and on the other, Georgians should also become more open and admit that not all Russians are “occupiers”.

“I want to tell Georgians that what often looks like an imperialist, colonialist attitude is actually fear and confusion. It is very important to share your fears, dissatisfaction and desires with each other. For example, I want the Georgians to ask us directly — how long have you been here? why did you come? And we will give them a direct answer and say that we simply had no choice. Only individual and human relationships will break down the wall that has been built between us.”

Russians in Georgia