All the details of the case against Georgian journalist Mzia Amaglobeli

Mzia Amaglobeli’s verdict postponed

The sentencing in the case of Mzia Amaglobeli, founder and director of the popular Georgian outlets Batumelebi and Netgazeti, has been postponed until August 4.

Mzia Amaglobeli has become the first journalist to face trial in Georgia.

She was arrested in January 2025 for slapping the Batumi police chief during a protest after he insulted her.

This was classified as “assaulting a police officer,” and she now faces four to seven years in prison.

Mzia was 23 when she and her friend Eter Turadze founded the newspaper Batumelebi. It was the early 2000s, during the authoritarian rule of Aslan Abashidze in the autonomous republic of Adjara, where they both lived, and no independent media existed in the region. “Back then, we managed to break away from the flattering, propagandistic, Soviet-style journalism,” Mzia Amaglobeli said in court.

The outlets Batumelebi and Netgazeti are known for their critical approach and high-quality journalism. They have received numerous international awards, including the European Press Prize.

On August 1, the 202nd day of Mzia Amaglobeli’s detention, Batumi City Court spent nine hours hearing the closing arguments of her lawyers.

At 10:30 p.m., the judge decided to postpone the hearing at Mzia’s own request. She said she wanted to make her final statement but after so many hours in court, she had “no strength left to speak or even to listen.”

Once again, Mzia was not allowed to sit next to her lawyer during the hearing. She spent all nine hours in a glass booth – standing or walking inside, taking notes, occasionally looking toward the courtroom and trying to comfort friends and family with a calm smile.

The atmosphere inside and outside the courtroom

The courtroom was packed. Among those present were ambassadors and representatives from several Western embassies, including Sweden, Norway, France, Germany, the Czech Republic (including the ambassador himself), the Netherlands, Poland, Lithuania, and the European Union.

The 5th president of Georgia, Salome Zourabichvili, was also in attendance.

During breaks, the courtroom greeted every entrance and exit of Mzia with applause and chants of “We love you, Mzia!” and “Freedom for Mzia!”

Outside the courthouse, hundreds of people stood or sat on curbs and even on the pavement to support Mzia. Activists, journalists, and concerned citizens traveled from Tbilisi and other cities to show solidarity.

Also in the courtyard were mothers of several detained participants of the pro-European protests that have been ongoing in Georgia for more than eight months. People chanted: “Freedom for Mzia!”, “Freedom for political prisoners!”, “Down with oligarchy!”

“This is not a trial of Mzia Amaglobeli, it is a trial of Georgian Dream. They have condemned themselves,” said Zviad Koridze, a representative of Transparency International Georgia, before the hearing.

“Mzia should not be in prison. This is the wish of a few individuals who want to punish her and intimidate us, journalists,” said Eter Turadze, editor of the newspaper Batumelebi.

“Mzia, stay strong! You are a strong woman, and we take example from you,” said the mother of detained pro-European protester Zviad Tsetskhladze.

“This verdict will be a verdict for everyone involved in this unjust case. First and foremost, for Police Chief Irakli Dgebuadze, who has now gone down in history as ‘red cheek’ (from Dgebuadze’s own testimony describing how Mzia slapped him). It will be a verdict for all political leaders, starting with Bidzina Ivanishvili (honorary chairman of Georgian Dream, oligarch, and widely considered Georgia’s shadow ruler),” said the 5th president of Georgia, Salome Zourabichvili.

Closing statement by lawyer Maia Mtsariashvili

At around eight o’clock, lawyer Maia Mtsariashvili, relying on arguments and documents, calmly and firmly explained why Mzia Amaglobeli is a prisoner of the regime.

Mtsariashvili spoke about the publications founded by Mzia and the projects she implemented. She provided specific details of the unfair investigation into her case.

Among many examples, Mtsariashvili noted that the investigation didn’t even question Mzia. She presented evidence of “false testimony,” including very similar wording in the statements of the questioned police officers.

The lawyer devoted much time to the attacks on Mzia by representatives of the ruling Georgian Dream party. Mzia was constantly labeled a “dangerous criminal” and was urged to repent and confess guilt, which violates the presumption of innocence, she said.

“I have a question for you,” Maia Mtsariashvili addressed the judge. “Will you be able to withstand the pressure from representatives of the highest authorities in the country — after all, they have already passed judgment on Mzia Amaglobeli? Forgive me, but I don’t believe you can. I don’t believe anyone in the country’s judicial system is capable of doing that today.”

The lawyer refuted the prosecutor’s claim that “Mzia Amaglobeli attacked the Batumi police chief.” A slap is not an attack, she stated.

“In the explanatory dictionary by Chikobava, a strike with an outstretched hand to the face is called a slap. We are talking specifically about a slap, not an attack — this is a crucial point. A slap is a slap, no matter what you call it. You can call it a terrorist act, but it will still remain a slap in the perception of society,” Mtsariashvili said.

Concluding her speech, the lawyer said that “this is a case that will be talked about for many years to come.”

“The case of Mzia Amaglobeli is a mirror. Looking into it, you see how leaders abuse their power. You see how the prosecution tries to portray the victim as the criminal, and the criminal as the victim,” Mtsariashvili said.

The courtroom greeted the end of her speech with loud applause and cries of support.

Judge Nino Sakhelashvili remained silent throughout the entire session.

While the lawyer was speaking, she constantly shuffled through and reviewed documents, occasionally nodding at the lawyer or glancing at Mzia, who stood calmly and stubbornly on her feet in her booth.

The judge’s patience ran out when it was time for another lawyer, Juba Katamadze, to speak. The judge stated that she would give him only three minutes. She also warned that if anyone wanted to say something in defense, this session was the last opportunity to do so.

The arrest

Mzia Amaglobeli was arrested twice during a protest outside the police station in Batumi, a city in southwestern Georgia, on the night of January 11–12, 2025.

The first arrest came after she stuck a sticker on the police building calling for a general strike. She was released on bail a few hours later.

But soon after, she was arrested again – this time for slapping the head of the city’s police, Irakli Dgebuadze, following repeated verbal abuse directed at her. The incident was preceded by a clash between protesters and the police, with eyewitnesses reporting provocative actions by the security forces.

Eter Turadze, chief editor of the newspaper Batumelebi, recounts that after Mzia Amaglobeli’s release, she stood together with relatives and supporters. The atmosphere was calm, and the participants were already preparing to disperse when the Batumi police chief, Irakli Dgebuadze, began arguing with the crowd.

At that moment, the police arrested two of Mzia’s relatives right before her eyes. A video recorded that same evening shows Amaglobeli falling during the crush that started around this arrest. It was at that moment that she slapped Dgebuadze.

It was the 43rd consecutive day of protests in Batumi. Mzia Amaghlobeli had not taken part in the rallies until that night – she joined after police detained her friend, activist Tsiala Katamidze, and began using force against other demonstrators.

After her arrest, Mzia Amaglobeli became a victim of inhumane treatment. For three hours following the arrest, the journalist was denied access to a lawyer. In court, she gave a detailed account of how the police officer Dgebuadze spat in her face, tried to hit her, and refused to let her have water or go to the restroom.

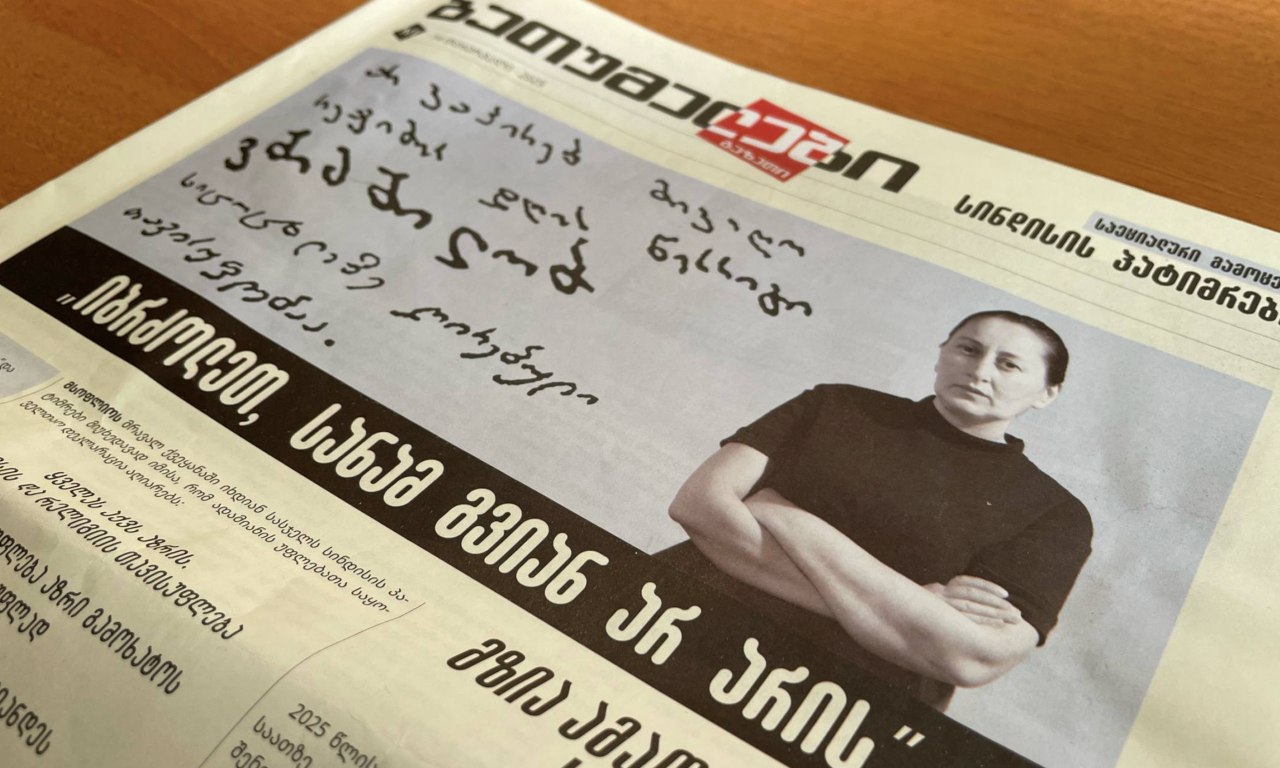

At her first court appearance, Amaghlobeli brought a copy of How to Stand Up to a Dictator by Maria Ressa, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning journalist from the Philippines — a gesture that quickly became a symbol of the case and of the wider fight for press freedom in Georgia.

Many activists still bring the book to protests and court hearings in politically motivated cases.

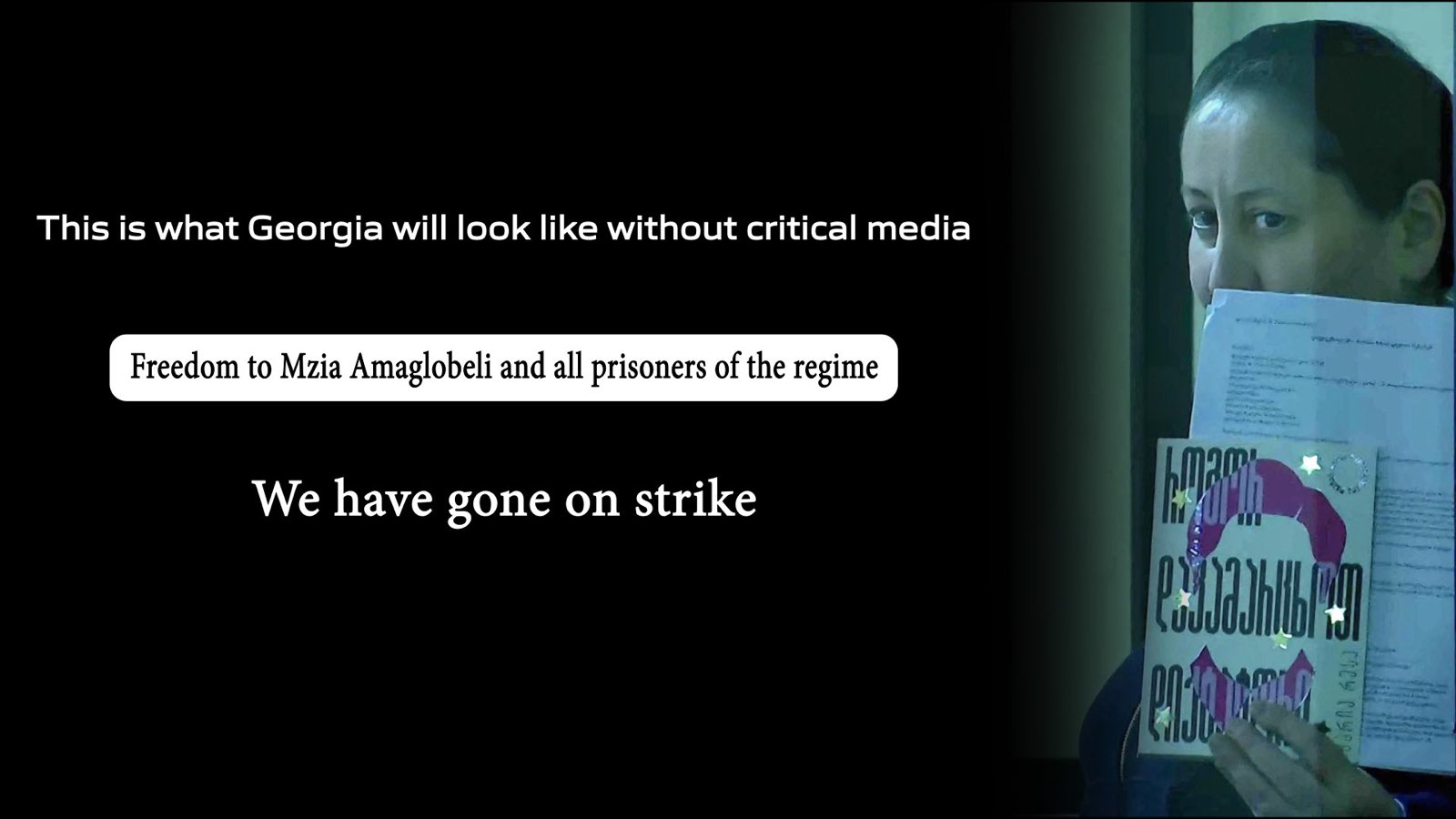

Immediately after her arrest, Mzia Amaglobeli went on a hunger strike that lasted 38 days. In letters to her colleagues, she stressed that it was a protest against injustice — not an attempt to pressure the investigation.

“Fight until it’s too late,” she said, and throughout all seven months of pretrial detention, she set an example of this struggle herself: with her calmness, stubbornness, and “excessive kindness,” as noted by the prison psychologist in their report.

Pretrial detention was imposed as a preventive measure, with prosecutors claiming that if released, she might “influence witnesses.” Yet all the witnesses in the case were police officers, raising questions about how a journalist could possibly exert influence over them.

During her time in prison, Amaglobeli nearly lost her eyesight. According to the most recent medical report from February, one eye is completely blind and the other has just 10% vision left.

Three cases against the journalist

Georgia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs opened three cases against her: in addition to the criminal charge of assaulting a police officer, she was also charged with two administrative offences over the sticker incident.

She was found guilty in both administrative cases – on March 18 and June 18 – and fined a total of 3,000 lari (about $1,100).

The officer’s cheek turned red

The entire criminal case for assaulting a police officer hinged on the claim that the slap Mzia Amaghlobeli gave to Batumi’s police chief was extremely painful – so much so that Irakli Dgebuadze’s cheek turned red.

For seven months, investigators tried to determine just how painful the slap was, whether only his cheek was red or his ear too, when exactly he felt the pain, when he noticed the redness, and so on.

“When [Dgebuadze was slapped], the sound was so loud that the protest immediately stopped,” former head of the Adjara police department Grigol Beselia told the court.

Dgebuadze’s reddened cheek quickly became the subject of widespread mockery online.

“Why did the pain I felt amuse society so much? Do you understand what it’s like to be hit in the face?” Dgebuadze protested during the trial.

During the proceedings, the lawyers noticed that Dgebuadze’s ear turned red even while he was giving testimony in court. When lawyer Maia Mtsariashvili pointed this out aloud, he replied, “It’s hot in the courtroom, that’s why my ear is red.”

Violations in the case

Mzia Amaghlobeli’s case was riddled with false testimony and fabricated reports.

Here is the English translation of your text:

All prosecution witnesses were police officers. All of them, using the same words, claimed that at the moment of Amaglobeli’s arrest, all three surveillance cameras were turned off. They all described the slap in the same way: “Mzia grabbed Dgebuadze by his police jacket, tore it, and pulled him toward herself.”

One officer alleged that Mzia insulted them, calling them “dogs,” “pigs,” and “Russia’s slaves.”

“I’m 50 years old. I don’t even know how to swear,” Amaghlobeli responded. “No one has ever heard me use foul language — not in public, not in private.” She then offered to recount the insults that police officers themselves had hurled at her.

Here is the English translation of your text:

The case against Mzia Amaglobeli also involves falsified protocols, her lawyers claim.

During her first arrest, when she put up a poster, Irakli Dgebuadze stated on camera that she was detained under Article 150 of the Administrative Offenses Code.

Later, however, it became clear that this article does not allow for detention.

At that point, the police produced an “updated version” of the protocol — which cited Article 173 (resistance to a police officer).

According to the lawyers, Mzia Amaglobeli’s action is not an attack on a police officer, but rather an insult.

This is the exact word recorded in the statement on the basis of which the investigation was launched. And the law does not classify insult as a criminal offense.

Meanwhile, state propaganda began actively working on this topic.

The entire system was involved: from the Georgian Dream prime minister to the tax service.

High-ranking public figures violated the presumption of innocence by claiming that she committed the crime on order, in exchange for a “fee.”

However, the judge denied the lawyers’ requests to question those who made these claims in court and to compel them to present evidence and disclose the source of their information.

At one of the final hearings on July 21, the prosecution raised the possibility of a plea deal — but Mzia Amaghlobeli firmly rejected it, insisting once again that she was innocent.

Huge international response

From the moment of her arrest, Mzia Amaghlobeli drew international attention. Statements of support came from the highest platforms, and representatives of diplomatic missions regularly attended her court hearings.

On June 19, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on media freedom in Georgia – and specifically on Amaghlobeli’s case – by a vote of 324 to 25. The resolution stated that Mzia Amaghlobeli was “being punished for exposing corruption and reporting on fraud during the 2024 parliamentary elections.”

Her case has been closely followed by several international organisations, including Amnesty International and the Clooney Foundation for Justice TrialWatch.

Since 2019, the Clooney Foundation has been monitoring cases in more than 40 countries. Currently, the foundation is working on cases involving about 60 journalists in 10 countries, including Mzia’s case.

In its preliminary findings, it noted several concerns — including the abuse Amaghlobeli faced after her arrest — and highlighted the authorities’ failure to investigate. It also pointed to the disproportionate nature of the charges.

Numerous domestic and international organisations have declared that Mzia Amaghlobeli is a political prisoner.

“Mzia Amaghlobeli qualifies as a political prisoner under the definition set by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe,” the first report by Transparency International Georgia states.

According to the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, her case “demonstrates that Georgia’s judiciary is no longer fulfilling its core functions and is issuing politically motivated rulings.“

The case has now reached the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). The complaint argues that multiple fundamental rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights have been violated — including the right to liberty and security, the right to a fair trial, the right to privacy, and the right to freedom of expression.

The court has already begun reviewing the case, and the Young Lawyers’ Association believes it may be granted high-profile status.

News in Georgia