Ukrainian refugees: Here to take? Common myths about refugees in Europe

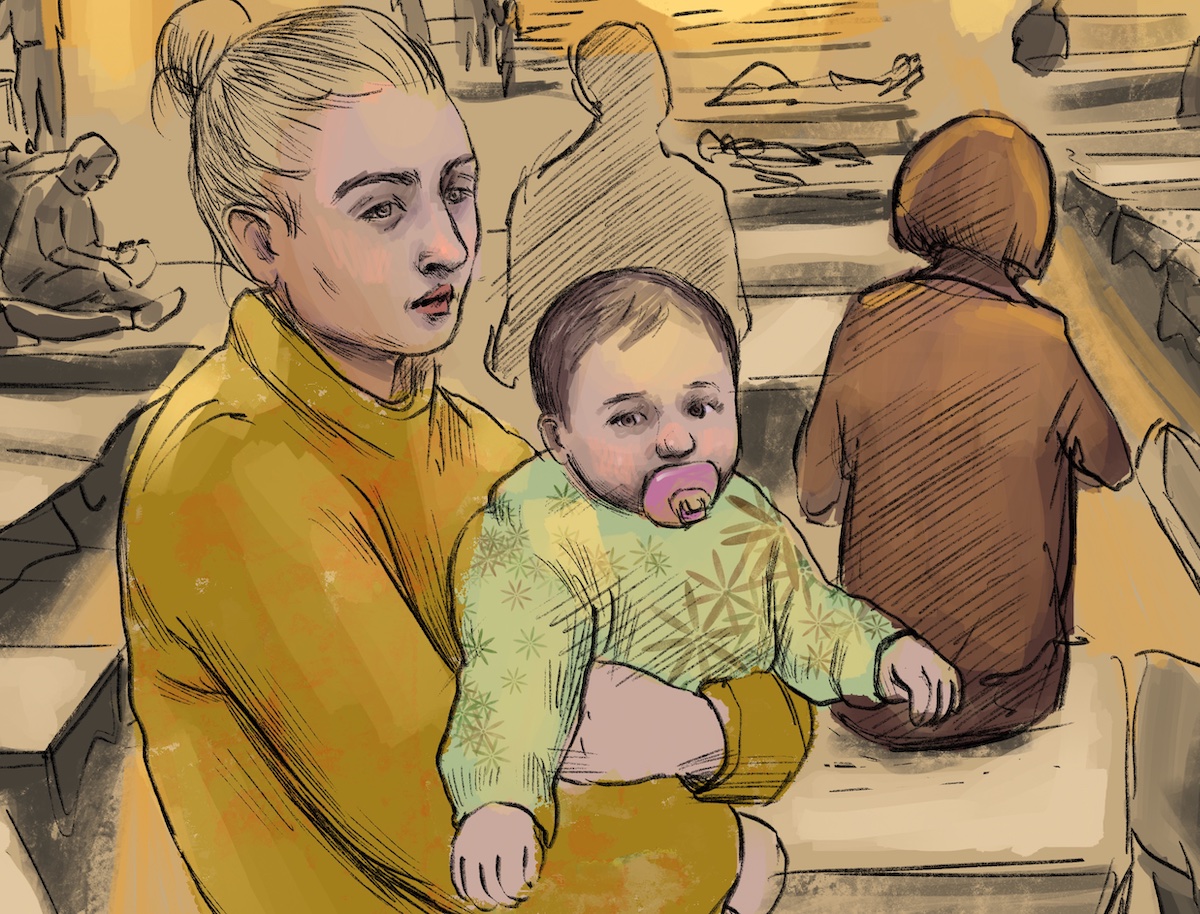

Ukrainian refugees in Europe

The full-scale war in Ukraine has led to an exodus of Ukrainians abroad, primarily to the West. According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), as of mid-June 2024, nearly 6 million Ukrainians are in European countries.

The highest number of Ukrainian citizens received temporary protection in Germany—1.1 million, followed by Poland with 957,000, and the Czech Republic with 346,000. Germany only surpassed Poland, which shares a border and a similar language with Ukraine, in 2023. Factors in this intra-European migration include larger social benefits, higher wages, and integration initiatives by the German government. Additional reasons for relocation are positive feedback from Ukrainians who settled there earlier and the desire to provide their children with quality European education.

Job hunting and learning new languages, integrating into European communities, and trying to maintain mental health while worrying about relatives and friends left behind in Ukraine—these are the common challenges Ukrainian refugees face abroad. They also deal with generalized refugee stereotypes within Europe and a lack of understanding back home, leading to a loss of shared identity.

Ukrainians abroad and Ukrainians in Ukraine

Today, more than 280 million people—3.6% of the global population—live in countries where they were not born, though not all of them are refugees. Collectively, migrants worldwide make up the fourth largest “country” by population. Moreover, even more people are willing to migrate if given the opportunity. The main factors driving migration are socio-economic (for voluntary migration) and safety, as in the case of Ukrainians.

Zaborona conducted a survey among its readers, inviting them to anonymously share their opinions on choosing to stay in Ukraine or leave, as well as on migration stereotypes.

According to the survey, the reasons for going abroad include:

- War

- Personal and family safety

- Occupation or threat of occupation of one’s place of residence, fear of re-occupation (for residents of territories seized by Russia in 2014)

- Availability of work abroad

- Concern for children’s future

- Loss of home or family

- Lack of opportunities for self-realization in Ukraine

- Doubts about the effectiveness of government institutions

Ukrainians who stayed in the country explain their choice as follows:

- No opportunity to leave

- Family (some have elderly parents who refuse or are unable to leave due to health reasons; some have spouses who are conscripted or already serving)

- Support for the country, patriotism

- Being in a relatively safe place

- Moral values

The information from the Zaborona survey aligns with data from the Rating Lab. Comparing opportunities, Ukrainians conclude that Europe offers jobs, protection, income, comfort, and infrastructure, while Ukraine provides services and amenities, including medical and partially educational services, business opportunities, and affordable housing. Success can be equally achieved both in Ukraine and Europe.

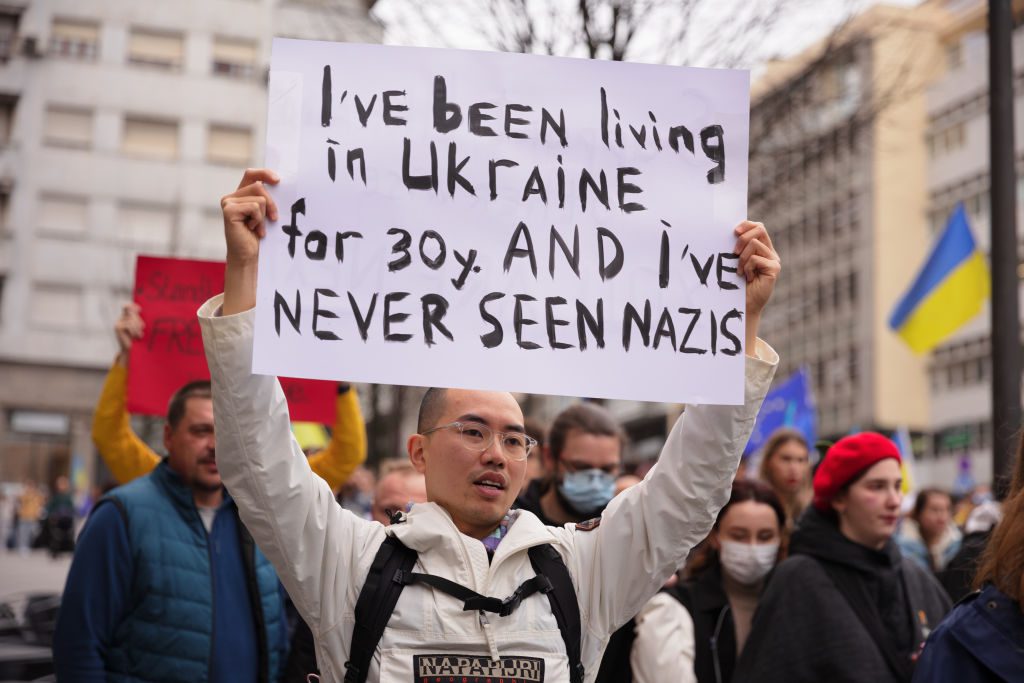

Myth 1: Migrants take jobs from locals

Discussions about Ukrainian refugees attempting to take jobs from citizens of their host countries occasionally surface on social media. This phenomenon was explored in the report “They Will Come and Take: Anti-Ukrainian Hate Speech on Polish Twitter” by Ada Tymińska, a human rights advocate with the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights in Poland. Despite the sympathy towards Ukrainians being unquestioned at the time of the report’s publication in April 2023, the researcher predicted that anti-Ukrainian sentiments would inevitably resurface in more favorable circumstances, as the active support for refugees naturally wanes due to fatigue.

“Changes in attitudes only arise from fears for one’s own well-being,” says Ada Tymińska. “If a less rational politician suddenly claims that Ukrainians will come and take jobs or social benefits, some people will agree with them.”

In Poland, anti-Ukrainian sentiments are being fueled by the pro-Russian far-right party “Confederation,” which actively opposes the “Ukrainization of Poland,” blocks border crossings on the Polish-Ukrainian border, and calls for limiting benefits to refugees. Meanwhile, farmers, whose interests “Confederation” supposedly protects, are already complaining about a shortage of seasonal workers.

“I suggest recalling the statements of Polish farmers in the spring, that there would be no one to pick strawberries or do low-skilled jobs,” says Vasyl Voskoboinyk, president of the All-Ukrainian Association of International Employment Companies. “Usually, incoming people cannot compete for high-paying positions; they fill market niches where there is less demand among the local population. Similarly, Poles preferred to go to Germany to pick asparagus because such work is better paid in neighboring countries.”

The Polish Economic Institute (PEI) claims that the employment rate of Ukrainians in Poland is currently the highest among OECD countries. However, Ukrainian refugees face various challenges in the Polish labor market and sometimes experience unequal treatment.

“Refugees find it harder to have their qualifications recognized, and they often work below their skill level or in the informal economy. National discrimination is not widespread,” explains Radosław Żyżyk, senior advisor of the PEI Behavioral Economics team. “Those who have faced or heard of discrimination point to low wages, exploitation of their vulnerability in the labor market, unequal treatment and workloads, and harmful stereotypes.”

In an experiment (PEI report “Ukrainian Refugees in the Polish Labor Market: Opportunities and Obstacles,” March 2024), it was found that in several industries where special qualifications are not required, employers were 30% less likely to respond to resumes submitted by Ukrainian women compared to Polish women. Analysts note that this difference signals potential discrimination at the initial employment stage.

Marcin Kołodziejczyk, director of the International Recruitment Migration Platform EWL, notes that Poland has long faced a worker shortage. The need for labor is so great that people from all over the world, including Latin America and Asia, come to work in the country.

“The Polish labor market needs about half a million workers over the next five years,” says Marcin Kołodziejczyk. “Today, with Poland’s unemployment rate being the second lowest in Europe (3%), the labor shortage is felt in almost every industry, and the economy is growing (+2% in the first quarter of 2024). This is not about competition but about the demand for a large number of workers. There is enough work for everyone.”

The consistently low unemployment rate in Poland has also been noted by the “Ukrainian House” foundation in Warsaw in recent years. According to information from the Statistical Office, the influx of refugees into Poland has not had a significant impact.

“The fact is that recent polls show that among Poles, this stereotype is not as common as it might seem,” says Ukrainian House expert Oleksandr Pestrikov. He refers to another study by the Polish Economic Institute.

Only 30% of respondents believe that foreigners pose a threat to Polish workers. 23% are confident that foreigners can compete with skilled workers. 56% are convinced that the threat exists only for low-skilled workers.

“Locals are more afraid of wage dumping. Where a Pole demands higher pay, Ukrainians are willing to do the work for less,” says Pestrikov. “The Polish economy depends on cheap labor. This is both an advantage and a problem. It hinders the robotization and automation of industry, and workers do not want to remain cheap labor forever.”

According to the observations of the Ukrainian House expert, the phenomenon of casual work has almost disappeared in the last two years. Ukrainians in Poland are looking for stable jobs with weekends, sick leave, and vacations. And here a new problem arises: Polish society is ready to see Ukrainians as construction workers and waiters, but not as lawyers, managers, teachers, or shop owners.

“I was also told that Ukrainians don’t pay taxes because they don’t work or work unofficially,” says Inna, who ended up in Austria. “To which I reply that I would be happy to work officially full-time because I have an Austrian diploma, over ten years of Ukrainian work experience in my field, and fluent German. But where is the job?”

The Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs of the Czech Republic also confirms that Ukrainians are not taking jobs. According to its data, four out of five Ukrainians have found work in unskilled and unstable positions.

“Europe is currently experiencing rapid demographic aging. There is a shortage of labor everywhere,” comments Ella Libanova, an academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and director of the Ptoukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies. “Therefore, businesses are interested in having more workers. Ukrainians are not competitors to Europeans in terms of employment—they occupy different niches. This is always the case: migrants, especially in the first generation, take the jobs they are given. They do not displace locals. Yes, some competition arises, but it is not as significant as some might want to claim. This is an exaggeration.”

At the Ukrainian Center for Economic Strategy, it is observed that the economy does not have a fixed number of jobs occupied by either locals or migrants.

Daria Mikhailishina, Senior Economist at the Ukrainian Center for Economic Strategy, comments, ‘Immigrants stimulate the economy of the host country as they purchase goods and services here. To produce more goods and services, more jobs are needed. Therefore, immigrants typically do not occupy jobs held by local residents but contribute to economic growth, which creates a greater number of jobs. Additionally, in many European countries where a large number of Ukrainians have migrated, there is a shortage of labor due to low birth rates and an aging population, so Ukrainian migrants can help fill this gap.’

In a study published at the end of 2023 on the impact of large migration waves on OECD countries, it is noted that this phenomenon enhances domestic production and productivity in both the short and medium term. Economists from the International Monetary Fund conclude that as immigrants enter the labor market, local residents move into new professions, often requiring higher language and communication skills or performing more complex tasks. As they enhance their skills, productivity in the economy increases. The responsiveness of physical capital (investments) to increasing the workforce is also a key element in creating dynamic advantages from immigration.

Myth 2: Large amounts from budgets are spent on resettlers, which could have been directed towards community development and other local expenditures

The stereotype that Ukrainians move to Europe for financial assistance and stay for social benefits is quite common among both locals and those who remain in Ukraine (as evidenced by Zaborona’s survey responses).

“In Germany, many believe that Ukrainians stay here just to receive social assistance and that they don’t want to work. I work as an interpreter for Ukrainians during live conversations in various institutions. It’s very frustrating that this stereotype is often justified,” shared a Ukrainian.

However, nearly everyone who participated in the survey and belongs to the group living abroad states that they work. Women with children emphasize that the payments are very modest: “It’s only enough for diapers and formula.”

In Poland and the Czech Republic, it has already been calculated that Ukrainian refugees who found themselves in these countries with the start of full-scale war more than compensated for the funds spent on them.

The Polish government spent 15 billion zlotys on support for refugees from Ukraine in 2022 (about 3 billion euros) and about 5 billion in 2023. This aid includes a one-time payment of 300 zlotys (70 euros), a monthly child benefit of 500 zlotys, which increased to 800 zlotys (187 euros) from January 2024. However, only 7% of Ukrainian refugees live on Polish social assistance, which is one of the smallest in the EU.

Almost 80% of Ukrainians who arrived in Poland due to the full-scale invasion work and support themselves. The EWL migration platform’s study confirms that Ukrainian refugees started looking for work from the first weeks of their stay in Poland, changing jobs over the year, seeking opportunities for professional growth.

In the Czech Republic, the balance of income and expenditures on support for Ukrainian refugees looked like this: in 2023, expenditures of 21.6 billion Czech crowns (858 million euros) still exceeded income of 21 billion crowns. However, in the first quarter of 2024, revenues predominated—6.4 billion Czech crowns (about 254 million euros) in taxes and fees against 3.5 billion crowns in assistance. It’s worth noting that 88% of Ukrainian refugees work in the Czech Republic.

About 80% of Ukrainian refugees in Germany live in partially subsidized apartments. Rent and housing expenses amount to 750-850 euros per person per month. Additionally, medical insurance, integration courses, and support for children and pensioners are provided.

In Germany’s employment centers, there are about 700,000 refugees with Ukrainian passports registered. They can receive 563 euros per month. There is also child support.

According to a report by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), the employment of Ukrainian refugees in Germany requires optimal integration over 10 years. Then, the average employment rate among Ukrainian refugees in the country will reach 55%. In five years, a figure of 45% can be expected. Employment is hindered by a high proportion of single mothers and relatively poor health conditions among refugees.

“The German government says that if 20% of Ukrainians are currently employed, they will be satisfied with an increase to 40%,” says Vasily Voskoboinik, president of the All-Ukrainian Association of Companies for International Employment. “The low percentage of employed in Germany is due to language requirements, and they also focus on highly qualified work, giving Ukrainians the opportunity to improve their qualifications or retrain to work not only with their hands. Currently, the government is simplifying employment conditions, reducing the language requirements for Ukrainians.”

He believes that Ukrainian refugees are not among those who rely solely on social assistance in Europe.

“When people went abroad in search of asylum, they weren’t looking for work, they were trying to get as far away from the combat zone as possible,” says Vasily Voskoboinik. “It’s inappropriate to say that Ukrainians came and became social dependents. Although there is a certain percentage. But no matter how much social assistance is paid, it won’t be enough for normal functioning. If there’s not enough money, Ukrainians will look for work. Some find work illegally, but they earn money.”

According to the survey by the Center for Economic Strategy, as of November 2022, 73% of Ukrainian refugees in Europe were receiving financial assistance, whereas as of January 2024, this figure had decreased to about 40%.

Nearly half of those surveyed in Germany (44%) and the Netherlands (40%), where social benefits are among the highest in Europe, state that while financial aid enables them to support themselves in their host countries, they are actively seeking employment. This is a key finding from the study “Unlocking Potential: Ukrainians in Germany and the Netherlands,” conducted by the Migration Platform EWL and the Center for Eastern European Studies at the University of Warsaw.

“Many European and global countries are providing assistance to Ukrainians displaced by the war,” says Daria Mikhaylishina, Senior Economist at the Center for Economic Strategy. “However, over time, the number of Ukrainians receiving assistance has significantly decreased due to changes in the policies of host countries and because many have already found employment and no longer require assistance. Moreover, the economies of host countries benefit more than they spend on assistance.”

Meanwhile, CES notes that Ukraine’s labor market keenly feels the impact of the full-scale war. The economic shock from the start of Russia’s invasion resulted in declines in both demand and labor supply — businesses were not hiring, and people were not seeking jobs. Subsequently, labor demand began to recover slowly; however, the number of job seekers surged as early as the summer of 2022, surpassing 2021 averages. However, trends diverged thereafter: the demand for labor continued to recover alongside economic restoration, while job seeker activity steadily declined, partly due to Ukrainians migrating abroad and mobilizing into defense forces.

Myth 3: Migrants do not pay taxes and do not contribute to economic development

Back in May 2022, Oxford Economics forecasted that if Poland were to retain 650 thousand Ukrainians, GDP could increase by 1.2% by 2030. If the number were to reach 1 million Ukrainians, the growth could be up to 2%, compared to scenarios without forced Ukrainian resettlements. Similar predictions were made by the National Bank of Ukraine, estimating that by 2026, thanks to Ukrainian refugees, Poland and the Czech Republic’s GDP could grow by 2.2-2.3%, and Germany’s by 0.6-0.65%.

In 2022, contributions to Poland’s state budget from Ukrainians ranged from 0.8% to 1.0%, increasing to 1.3-1.6% the following year. In monetary terms, this equates to 10.1-13.7 billion zlotys (approximately 2.34-3.18 billion euros) in 2022 and 14.7-19.9 billion zlotys in 2023. The study “Impact Analysis of Ukrainian Refugees on the Polish Economy,” commissioned by the UN, was conducted by the international consulting company Deloitte in collaboration with the Migration Platform EWL.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees report states that in the long term, as the economy fully adapts, this figure could rise to 0.9-1.35%.

“This has a significant impact on the Polish economy, considering the challenges posed by Russian aggression, the overall situation, and significant labor shortages in Poland,” says Martin Kolodziejczyk, Director of the International Recruitment Migration Platform EWL. “Ukrainians are saving the Polish labor market—both those who arrived before the full-scale invasion and military refugees.”

Therefore, since 2022, Ukrainians in Poland have been contributing to economic development by paying 10-14 billion zlotys in taxes, increasing to 15-20 billion zlotys in 2023. The majority of Ukrainian refugees also assist families in Ukraine, donate to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (VSU), or volunteer—reports from EWL in Poland and Germany attest to this.

“Recently, there was a study by experts from the United Kingdom, where there are significantly fewer Ukrainian migrants concentrated,” notes Ella Libanova, academic at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and director of the M.V. Ptukha Institute of Demography and Social Studies. “They state that the additional 0.2% of GDP is precisely the contribution of Ukrainian migrants. This is significant for Britain. Ukrainians live in Europe, work, pay taxes, and spend money. It is known that every zloty spent in Poland contributes to the Polish economy.”

According to a survey by the Center for Economic Strategy as of January 2024, 45% of Ukrainians who have moved abroad are employed or have become entrepreneurs, thus paying taxes on their income from work or business. All migrants pay at least consumption taxes, value-added tax, by purchasing any goods and services.

“Let’s not forget that in Poland and the Czech Republic, locals were paid for providing housing,” emphasizes Vasily Voskoboynik, president of the All-Ukrainian Association of Companies for International Employment. “Speaking of Polish assistance of 800+ per child [a monthly payment of 800 zlotys per child under 18], it is clear that this money will be used for the child, enter the budget, and remain in the country’s circulation, contributing to economic development.”

“To avoid being dependent on anyone, in Poland I started my own business from scratch,” says Yelizaveta. “I found my first sneakers for my mom in a dumpster. There I also got a coffee machine and a kettle for an empty apartment. At first, I traveled for orders with a small suitcase of tools, and now ten masters work in my permanent makeup studio in Warsaw. We have a high price, and 80% of our clients are locals.”

Myth 4: Worsening сrime rates

While this stereotype is more often applied to people from non-European cultures, some locals might generalize the concept of “refugees” and apply this thinking to all.

At the beginning of 2024, the Ukrainian House Foundation in Warsaw was forced to publicly respond to an article in Rzeczpospolita. The article claimed that the “influx of thousands of foreigners following the outbreak of war in Ukraine has been reflected in crime statistics.” In an open letter to the editorial office, the foundation reasonably suggested that there were likely certain reasons and prerequisites (events, alarming survey results, xenophobic statements by politicians) that prompted Rzeczpospolita to publish crime statistics involving non-citizens in Poland.

“It would be fair to outline these reasons and explain your intentions in writing the article,” the letter states. “It is troubling that a serious newspaper, shaping public opinion, resorts to ethnic profiling and manipulation of cultural differences.”

Experts from the foundation worked with the figures published in the article and concluded that the 17,278 foreigners who committed crimes in 2023 were responsible for only about 2% of all crimes. Additionally, the 3,240 thefts committed by foreigners accounted for approximately 3% of all thefts in Poland, and the 2,451 drug possession charges made up 4% of all such charges. Moreover, the crime growth rate among migrants is 7.7 times lower than the increase in the number of foreigners themselves.

“The stereotype of deteriorating crime rates due to refugees is something I have encountered only among Polish journalists,” comments Aleksander Pestrikov, an expert from the Ukrainian House. “They often like to emphasize the nationality of suspects and convicts.”

Incidentally, in a survey of Polish citizens for a report by Robert-Miron Staniszewski from the University of Warsaw on the social perception of refugees from Ukraine, fear of worsening crime rates did not rank first among threats from Ukrainians. Current concerns include the negative impact on the labor market.

“As for crime rates due to migrants, this exists but does not concern Ukrainians,” says Nadejda, who settled in Germany. “In our neighborhood, beggars—mainly Roma from Romania—sit outside supermarkets. It seems they only annoy me—the locals treat them kindly, even though they are all of working age. Germans say that in the early 2000s it was especially dangerous on the streets when Italians clashed with Serbs.”

“Ukrainians predominantly work,” asserts Ella Libanova. “There are very few men among Ukrainian migrants, mostly women and children. Therefore, it is unlikely that they significantly worsen the crime situation.”

Vasily Voskoboynyk, president of the All-Ukrainian Association of Companies for International Employment, draws parallels with the USA.

“We remember America in the 1920s-30s when the Italian mafia appeared there. But we must understand that people were coming from a poor country, unable to earn legal money to live at the level they dreamed of, so they formed groups,” says the expert. “But if 80% of those who left are women and children, it is unlikely that Ukrainian women will form some sort of female mafia.”

Aleksander Pestrikov notes that there are no special data on Ukrainian crime rates in Poland, but preliminary studies on migrant crime in general show a standard trend: crime rates among foreigners are lower than among local citizens, if only because they face deportation.

“The main stereotype attributed to Ukrainians is the tendency to drive under the influence,” asserts an expert from the Ukrainian House. “They are also accused of theft and a tendency toward domestic violence.”

At the same time, Ukrainian women suffer from psychological violence triggered by the stereotype that “Ukrainian women are prostitutes.” After the release of the program “Immigrants for Swedes” on Swedish television (SVT), where comedienne Elaf Ali joked that Ukrainian women are a common sight in Swedish brothels, a Ukrainian woman in a local club heard from a stranger that she is a prostitute, “because that’s what they say on TV.”

Myth 5: Refugees increase the strain on the healthcare system, education system, and housing market

Experts predict that the issues of long waits for doctors, pressure on the education system, and rising housing prices could become the biggest problems and reasons for worsening attitudes of Europeans towards Ukrainians. Ukrainians will face challenges not only from the less socially protected locals but also from those whose jobs the Ukrainian refugees largely do not compete for.

“Poles have a low level of trust in their own government and recognize the inefficiency of the government when it comes to social services,” notes Ada Timinska, a human rights advocate with the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights in Poland and a researcher on anti-Ukrainian hate speech in Polish social networks. “In Poland, there are long waits to see a doctor, and it’s difficult to enroll a child in kindergarten — that’s true. So, the sudden arrival of new people creates a sense of increased threat. However, problems with access to specialized medical care existed even before the arrival of Ukrainians. This only highlights that the state is ineffective in some aspects.”

Respondents in a Zaborona survey also spoke about problems in the healthcare and education systems in countries with a significant number of Ukrainian refugees. For instance, one woman in Germany was offered an appointment with a mammologist in seven months, and another couldn’t find a place in a kindergarten in a Czech city.

“People are arriving, and the load [on the healthcare and education systems] is increasing. But there are also more jobs,” notes Ella Libanova, an academic at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and director of the M.V. Ptukha Institute of Demography and Social Studies. “Among Ukrainian migrants, there are many medical and educational workers. What prevents schools with Ukrainian students from hiring Ukrainian teachers? This not only provides employment for Ukrainian women but also simplifies the education process for the children.”

Alexander Pestrikov predicts that problems in the educational sphere will worsen by the fall of 2024 when all Ukrainian children will be required to attend Polish schools. Until now, parents could decide whether to keep their children in Ukrainian online schools. This will mean more children in classrooms, more conflicts, parental disputes, and bullying.

Temporary status grants access to healthcare in Poland. “But the fact is, if you have to pay for housing and live on something, you have to work,” says Yelena, who came from Ukraine. “And when you work, you have healthcare even without status because you pay contributions from your salary. Your place in the queue to see a doctor is legally paid for.”

The Ukrainian House Foundation analyzed data from the healthcare system for 2022. During the first year of the war, 0.5 billion zlotys were spent on Ukrainians, although 2 billion were planned. It turned out that Ukrainian refugees utilized less than half of the amount allocated for them through the National Health Fund.

“Before 2022, most of our citizens in Poland were young, childless people who simply did not go to hospitals,” explains expert Alexander Pestrikov. “Meanwhile, there are now many mothers, children, older people, and individuals who pay close attention to their health among the refugees. They are just starting to be seen in hospitals, and it’s becoming difficult to convince the average Pole that Ukrainians are not a threat.”

According to the study “Social Perception of Refugees from Ukraine, Migrants, and the Actions of the Polish and Ukrainian States” by the University of Warsaw and the University of Economics and Humanities in Warsaw, the most common reason for negative attitudes towards Ukrainian refugees among Poles is the alleged “dependence” of Ukrainians. Respondents pointed out for the first time the “Eastern mentality, Soviet culture,” which manifests in a lack of concern for the common good. Many Poles claim that Ukrainians have demands for social benefits, believe everything should be free for them, and want to have the same rights as Poles.

“There was a shortage of doctors and teachers in Poland even before the war, and there are still many vacancies now, so they hire Ukrainians,” says Natalia, a Ukrainian. “Our people are taught to work well, carefully, and responsibly, so in many areas, even locals prefer to receive services from Ukrainians, especially in the beauty, food preparation, and repair sectors.”

Alexander Pestrikov notes that there has not been a single case where a Pole was deprived of something because it was given to Ukrainians: “However, this does not prevent pro-Russian parties from outright stating that the government now has not only its own citizens but also the citizens of a neighboring country on its welfare. This stereotype is very widespread.”

As an argument in favor of the conspiracy theory that locals tend to believe, he cites a new poll showing that over 60% of Polish citizens agree with the statement that Poles in Poland are now becoming “second-class citizens,” while Ukrainians have received undue privileges.

“The housing situation is more complex,” notes Alexander Pestrikov. “In 2022, prices did start to rise, and for example, in Warsaw, housing accessible to students almost disappeared. This is indeed related to the influx of Ukrainians, but now prices have almost returned to 2021 levels.”

Viktor, who settled in the Czech Republic, acknowledges that the arrival of Ukrainians has affected the real estate market: “But the apartments are rented out by locals. So, it’s the locals’ money that they can use for their lives or for improving the condition of their housing. Stereotypes about Ukrainians are spread mostly by less educated people, including right-wing radicals.”

Among other stereotypes faced by Ukrainian citizens abroad is the idea that “if you’re fleeing from war, you have nothing and never will.”

“In the eyes of foreigners, we [Ukrainians] should literally look homeless, without money for bread,” a girl shares in a survey by Zaborona. “Very often foreigners forget that before the war, we were successful in our fields. So, having a car is normal. Having a dress or jeans is also normal. As is taking care of your hair and body.”

Some foreigners are surprised that Ukrainians have very good education and qualifications. “We have to explain that we fled not from poverty but from war. Some don’t understand how we know 3-4 languages at once. And very often, out of surprise, they say something like ‘wow, what great English, where did you learn it?’ notes another participant in the Zaborona study.

Misunderstandings between Ukrainians and the return home

On the other hand, Ukrainians who have decided to stay abroad share the experience of being seen at home as cowards and traitors who don’t care about the fate of the state. It’s as if they are living their best lives abroad, have forgotten about Ukraine, and are indifferent to the war. They are believed to have left not for safety reasons but for bigger money, and that they neither donate nor help.

According to calculations by the Center for Economic Strategy, between 860,000 and 2.7 million Ukrainians may remain abroad. These are mainly promising, educated Ukrainians, students, mothers with children, who will later be joined by their men. Older people or people with lower levels of education are more likely to return to Ukraine after the war.

The non-return of Ukrainians, according to the CES, will have a significant impact on the Ukrainian economy, which could lose between 2.55% and 7.71% of GDP.

“If half of those who left stay abroad, it will be a very serious blow for us,” says Ella Libanova, an academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and director of the M.V. Ptukha Institute of Demography and Social Research. “The issue of returning Ukrainians who left because of the war will be one of the most important challenges of the near future.”

The overall sentiment is confirmed by data from the OneUA international survey, which included more than 18,000 respondents in eight European countries. Ukrainian refugees living in Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Moldova, and Romania are more likely to indicate that they intend to return to Ukraine compared to refugees in the Netherlands and Germany. The main factors are social attachment and economic considerations.

In the Zaborona survey, only 11% of respondents mentioned changing their decision about whether to stay or return. The main obstacles to returning are the ongoing war and the unpredictability of the future. Respondents who plan to stay in Ukraine cite the lack of opportunity to leave and their love for the country as reasons. It’s important to note that those who chose to live abroad, besides feeling safe, also mention their love for Ukraine as an argument—they can donate and promote Ukrainian interests in other countries while being in safety.

This material was prepared and published with the support of the Science+ project.