The political adventures of the New Year's tree in Azerbaijan

After the fall of the iron curtain, the Soviet people discovered a lot of new things. Among these discoveries was that the fir-tree they cherished so much since childhood was not at all used as a New Year’s tree, but rather as a Christmas tree.

New Year’s itself was changing and evolving all that time along with, believe it or not, a change in the political sphere.

From Nowruz to Christmas

For many centuries, celebrating New Year in Azerbaijan, Iran, certain parts of Central Eurasia and the Asian part of Russia were timed to coincide with the day of the vernal equinox. That holiday was Nowruz.

In the first half of the 19th century, Nowruz was celebrated beyond the Baku ramparts, on Market Square where a monument to Fizuli, a poet, is located now. In those days there was a wasteland in that place (though it’s true that the wasteland was the whole area outside the fortress, for many kilometers around it).

It was that very place where people came on Nowruz to make bonfires and jump over the fires. In those times houses in the fortress were made of wood so open flames were strictly forbidden.

After 1810, Baku Khanate, like many others, was transferred to the Russian Empire, and an increase in the non-Muslim population played its role in replacing Nowruz by Christmas.

The city population started to increase dramatically in the early 1860s. It happened following an earthquake in Shemakha, a large city in Azerbaijan, and the beginning of the development of the oil industry. Some new parks were laid out in the city, including the most popular –the Governor’s Garden, while the boulevard was landscaped for evening promenades.

The change in the population’s ethnic and, first of all, religious composition (especially in its most well-off upper crust) resulted in lifestyle changes. Now both Nowruz and Christmas were celebrated in Baku.

For those who are unaware, Christmas is the same holiday as New Years, but celebrated according to the Roman calendar. For, as the ancient Church Fathers decided, Jesus was lucky to be born on New Year’s day, or thereabout.

The first New Year tree was set up in Fountains Square in the 1870s for the public’s enjoyment, contemplation and as a meeting place to take part in festivities.

And the public did join in, especially the Muslim middle and upper class.

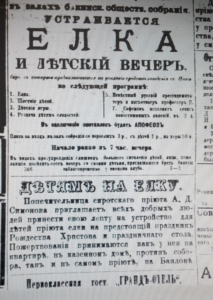

Established back in Western Europe, the tradition of holding charity balls and banquets finally reached Baku. While Dickens was writing about poor orphans freezing on Christmas eve in the snowy streets of London, the officers’ wives and sisters, merchants and oil producers in Baku were rushing with treats from one shelter to another.

Meanwhile, lists of philanthropists and benefactors were published on the front pages of local newspapers.

Shop sales are one more common feature that made the old pre-New Year’s Baku so similar to the present-day one. More than 40 photographer’s studios were operating in the city by the end of the 19th century. It was just as stylish then as it is today to have one’s photo taken. Many studios offered discounts at New Year’s. And confectioneries followed suit.

Then came the USSR

Judging by the New Year’s newspapers of Soviet times, life in the country had become boring but rich (and if not rich, it was about to become such, one just had to wait until all the enemies have perished): in the former Empire, including in Baku, the time had come for victorious atheism. The Christmas tree was banned as a vicious religious cult. But they didn’t come up with anything to replace it.

Pre-New Year’s and Christmas papers of the young Soviet Union were filled with front-page headlines screaming about increased milk yield and the speedy victory of world communism.

New Year’s, as well as 25 December and 7 January (Catholic and Orthodox Christmas) were declared as working days.

‘Only those, who’re friends of priests

Are eager to celebrate it at the Christmas tree

You and I are those priests’ foes

We don’t need these Christmas blows’ – such rhymes were disseminated among the public in the 1920s.

That’s how Valida Khanum describes those times, referring to her father: “He always told me that holidays were banned just because there was nothing to eat. He was a child in the 1930s and he told us how people were starving then. Of course they had celebrated nearly everything at home, but they hadn’t gotten a Christmas tree until the 1950s when I was born.

In the second half of the 1930s, the fir-tree slowly started to make a comeback, but this time as a New Year’s, rather than a Christmas decoration. It was then that the angel on the top of the fir-tree was replaced by the more politically appropriate red star.

Father Frost returns

After the division of post-war Europe, the USSR leadership realized that the victory of global communism was impossible. The industry started moving from military to civilian production. It was then in the second half of the 1950s that one of the world’s largest-scale housing construction projects was launched (‘Khrushchevkas’, tiny apartments-boxes where people were finally resettled from basements and communal flats).

People got separate flats, with fridges and, if lucky, TV-sets. And on TV there was ‘Morozko‘ (Jack Frost) and ‘Goluboy Ogonek‘ (Little Blue Light).

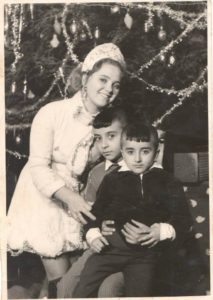

People were allowed to buy and openly decorate fir-trees. Children’s New Year matinees were also introduced in kindergartens, in which all children were dressed as standard Soviet bunnies.

“My brother and I had the most exclusive New Year in Surakhan (a settlement in Baku’s suburbs),” says Shahin. “It was in the 70s, when my parents both worked in the Palace of Culture after Orjonikidze. A New Year tree was put up there, accompanied by Father Frost, the Snow Maiden and clowns. They were genuine and funny, not like they are now. We had access to the room where Father Frost put on his make-up. And also, my brother and I received a surplus of gifts. As for the gifts, they didn’t vary much – just standard candy and biscuits.”

The last soviet years

Almost all of us remember them quite well and each of us has something to tell.

Katya: “For as long as I can remember, we used to have an artificial New Year’s tree that my mom bought in 1981 before I was born. For 20 years we used to decorate it, tying it to a radiator so that it wouldn’t fall.

“New Year ornaments were also of great value. People didn’t take bribes then and my grandmother, who worked in the maternity house, was given New Year’s ornaments after a baby was born.”

Irada: “We almost didn’t have any ornaments, and my father’s gift is my most vivid memory of that time. He made me a crown from the broken New Year tree ornament pieces. I received one more valuable gift in the 90s–two packets of Stimorol gum. I’m serious.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and gaining independence (especially after signing the notorious ‘Contract of the Century’ with the consortium of oil companies) it became possible and even necessary to celebrate New Year’s. Though the holiday acquired a kind of patriotic tinge, 31 December was declared, just in case, the Solidarity Day of World Azerbaijanis.

Similar to the pagan Nowruz and the Islamic Qurban Bayrami, the New Year is celebrated in a gaudy manner and on a grand scale. Unlike the Soviet Union, oil country Azerbaijan has never been inclined to asceticism. And therefore the New Year is celebrated with fireworks, boulevard concerts and public festivities.

This day is the most fruitful for the entertainment industry. Restaurants offer ‘packages’ of festive services starting from US 60 to infinity; local TV channels broadcast shows and concerts.

Azerbaijani social media users react ambiguously on this holiday, equally as on many other ones. Here are some typical comments:

“Shame on you! How dare you claim to be Muslims after that! You jump around the New Year’s tree like monkeys!”

“If that money had been spent on buying cartridges instead of your crackers, we would have regained Karabakh long time ago!”

Anyway, this year things were the same as last year and the year before it. There was a fireworks display on the Baku boulevard, a rapturous crowd, nicely decorated New Year trees around the city and the President’s televised address, during which he reported that Azerbaijan had managed to maintain economic stability.