Record reserve spending, looming sanctions: What's next for Georgian economy after October 26 elections?

Georgian economy’s future post-elections

In September and October, the National Bank of Georgia sold approximately $700 million from its foreign currency reserves — a record amount never seen before within such a short timeframe. What does this mean for Georgia’s economy, especially after the October 26 parliamentary elections?

_________________________________

The October 26 parliamentary elections in Georgia have heightened risks for the country’s economic development.

Local observers reported widespread voter pressure, systematic fraud, and significant violations. Western governments appear hesitant to recognize the election results, expressing doubts about whether they were conducted freely and fairly.

The legitimacy of the election results is in question, and economic risks are directly tied to this issue.

A failure by the West to recognize the elections could lead to sanctions. It remains unclear whether these sanctions will target individuals, as before, or escalate to measures isolating Georgia, such as revoking its visa-free regime with the EU.

Sanctions aimed at isolating the country would cause greater economic damage, but even targeted measures would leave a mark. This time, the list of sanctioned individuals could include Bidzina Ivanishvili and high-ranking Georgian government officials. However, when sanctions target acting government members, they essentially become sanctions against the entire country.

Given the uncertainty surrounding relations with the West in the coming months, it is difficult to precisely assess the economic impact of this process.

During the pre-election period, it became evident that negative expectations dominated among the population—nobody anticipated anything positive from the elections. This was reflected in the pressure on the exchange rate of the national currency, the Georgian lari (GEL).

When people expect unfavorable events ahead that could lead to the devaluation of the lari, they start stockpiling foreign currency and offloading lari. For example, deposits are converted from lari to dollars, while loans are converted from dollars to lari. This results in an immediate increase in demand for dollars in the currency market and devaluation of the lari.

This is exactly what happened in September and October. There was a widespread belief that the lari would devalue after the elections. This expectation was based not only on pessimistic sentiments but also on objective reasons. During the summer tourist season, Georgia receives more foreign currency than in the fall and winter, which helps support the lari’s exchange rate.

Additionally, this year (from January to September), remittances from abroad decreased by 22%. In the first half of the year, foreign direct investment dropped by 34%. The U.S. and EU countries had already announced suspensions or significant reductions in aid to the Georgian government.

On top of that, recent months have shown that sanctions imposed due to the adoption of the “Russian law” [referring to the “foreign agents” law] have significantly negatively affected the lari’s exchange rate. Despite the National Bank selling $190 million between April and June to stabilize the rate, the lari still devalued by 2%.

In September, a new wave of sanctions and lari devaluation began. However, the National Bank did everything possible to prevent the lari’s exchange rate from exceeding 2.74. To achieve this, $107 million was sold in September. When the National Bank sells dollars, it increases their availability to the population while simultaneously removing lari from circulation. This naturally helps strengthen the lari.

The exact amount sold by the National Bank in October is still unknown. It is known that $213 million was sold at currency auctions, but there is no data yet on how much was sold through “closed” transactions, the results of which will be published on November 25.

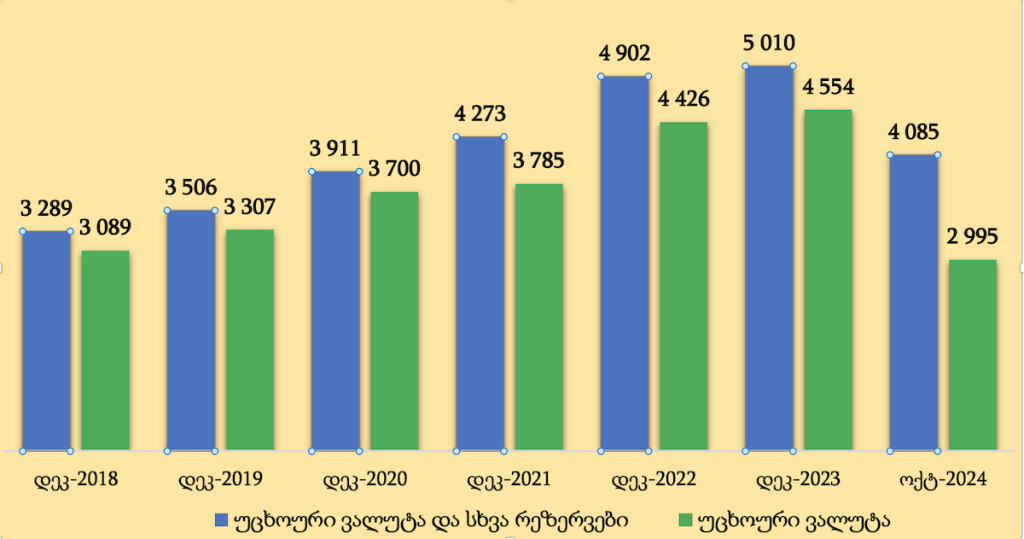

However, it is known that in October, the National Bank’s foreign reserves decreased by $640 million, indicating that approximately $400 million was sold through “closed” transactions. Thus, around $700 million was sold in total during September and October. This is a record amount—the National Bank has never sold such a large or even comparable amount in two months.

Because the National Bank maintained the lari’s exchange rate during the pre-election period and due to the reduced inflow of foreign currency into the country, foreign reserves shrank by $800 million over September and October.

As of October 31, the National Bank had $3 billion in reserves remaining. This is the lowest level since November 2018, effectively returning the country to figures from six years ago.

Foreign currency reserves are generally considered a guarantee of a country’s economic stability. Their use should be justified only in extraordinary circumstances, such as the 2020–2021 pandemic.

However, using reserves to support the national currency’s exchange rate during the pre-election period to benefit the ruling party is deemed unacceptable.

It is evident that without intervention, the lari’s exchange rate could have significantly declined. Nevertheless, if this is truly a temporary phenomenon related to election-driven speculation, as the National Bank claims, the exchange rate would have soon stabilized on its own.

However, on Election Day—October 26—the lari’s exchange rate could have been significantly higher, potentially influencing voter decisions. The government avoided this scenario, but the strategy cost the country $700 million in reserves.

Experts believe that the depletion of reserves will have a serious negative impact on the country’s economy. It is expected to lead to a downgrade in Georgia’s credit rating and a decline in investor confidence, which will, in turn, negatively affect future investment and capital inflows.

The sharp reduction in reserves also means that today, the National Bank is significantly less equipped to handle external economic shocks than it was at the end of August. This further undermines confidence in the country and its economic stability.

“The two-month criminal election campaign of Georgian Dream has inflicted greater damage on the National Bank’s reserves than the pandemic. It will take many years to recover. Over the past year, reserves have dropped significantly below the critical threshold.

Compared to external debt obligations, the reserve levels are not consistent with any BB-rated country. The issue of revising Georgia’s credit rating will soon become relevant,” said opposition MP, former head of the National Bank, and economist Roman Gotsiridze.

If this trend continues and the National Bank’s reserves continue to deplete at this rate, former Prime Minister of Georgia Nika Gilauri predicts “a major macroeconomic crisis”:

“We analyzed the statistics published by the National Bank and found that this is the largest reduction in reserves in the country’s history. $627 million in a single month—this amount has never been spent by the National Bank, even during the war with Russia, the pandemic, or other economic and global crises.

Over the last 30 years, no single month has seen such losses. In two months, Georgia’s foreign currency reserves have declined by 15–16%,” emphasized Gilauri.

According to Nika Gilauri’s forecast, within a month or two, the National Bank will have to allow the lari’s exchange rate to float freely:

“Maintaining the exchange rate in this way is possible if the National Bank believes these are short-term fluctuations or seasonal imbalances in supply and demand that will soon stabilize. However, it is clear that we are no longer in a phase of short-term fluctuations, and the exchange rate is evidently seeking a new equilibrium point.

Very soon, the National Bank will have to let the exchange rate go. Consequently, the rate will find a new equilibrium level, and it will become apparent that the National Bank wasted reserves instead of allowing the market to find this new equilibrium point,” noted Nika Gilauri.

What could sanctions mean for Georgia?

Georgia’s economy has proven highly vulnerable to Western sanctions, a fact clearly demonstrated over the past six months. Even the introduction of individual sanctions by the U.S. administration or Congress has caused the lari to depreciate and the stock prices of Georgian banks listed on the London Stock Exchange to drop sharply. The lari’s exchange rate and stock prices vividly illustrate how the economy and market participants react to such developments.

Georgia is heavily dependent on Western financial inflows, making its economy susceptible to both current and potential sanctions. In 2023, approximately $7 billion flowed into the country from Western nations (the U.S., EU, and UK). This total included $2.3 billion from exports of goods and services, $1.8 billion in remittances, $900 million in direct investments, and $2 billion in loans and grants to the government. Altogether, Western funding accounted for roughly one-quarter of Georgia’s economy.

Even the strictest sanctions would not entirely halt this $7 billion inflow. However, if 20–30% of that amount were to be cut off, Georgia’s economy would struggle to sustain itself—especially given the already depleted foreign reserves. Alternatively, the Georgian government would need to replace Western funding with capital from other countries, such as China or Russia, as seen in projects like the construction of the Anaklia port.

The collapse of Georgia’s economy would first manifest in a significant devaluation of the lari, followed by high inflation and rising prices. Stock values of major Georgian banks would drop to levels that could jeopardize the stability of the banking sector, potentially triggering panic among the population. The budget deficit and national debt would increase, and inflation would force the government to sharply raise interest rates. This, in turn, would lead to economic contraction, rising unemployment, and the country spiraling into deeper poverty.

In conclusion, the severity of Georgia’s economic challenges will depend on the West’s reaction and the steps taken by Georgian Dream. The ruling party must decide whether to make concessions or fully commit to an anti-Western course, with no intention of reversing it.

Georgian economy’s future post-elections