OSCE Minsk Group: An inglorious end to mediation in Karabakh

On April 8, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, after negotiations with his Armenian counterpart Ararat Mirzoyan, confirmed a fact that everyone knew about but never mentioned – the OSCE Minsk Group was no longer able to continue its mediation in the settlement of the Karabakh conflict.

Lavrov explained this by the fact that the other two co-chairs – the United States and France – did not want to work in the same format with Russia amid the war in Ukraine, he even accused them of “Russophobia”. This, of course, is an excuse. The real reason is that one of the parties to the conflict, namely Azerbaijan, is no longer interested in mediation in this format. Immediately after the end of the 44-day war, President Aliyev openly stated that 30 years of mediation by the Minsk Group had failed to yield any results, and Azerbaijan had decided to restore its territorial integrity on its own. Moreover, at a meeting with the co-chairs in Baku, in a rather harsh form for a diplomatic reception, he stated that “I did not invite you here”. Of course, you cannot reinforce your mediation if one of the parties to the conflict does not trust you (regardless of what the other side says).

In order to understand the reasons for the fiasco of the intermediary-monopolist, it is necessary to go back in history and remember how and why the Minsk Group was created.

The Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region began in the late 1980s. After the declaration of independence by the two neighboring Soviet republics in 1991, the conflict escalated into a real war.

In January 1992, both states were admitted to the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (as the OSCE was then called). At the same time, the idea arose that the CSCE could become a mediator in resolving the Karabakh conflict. Before the CSCE, Iran tried to fulfill this mission, since at that time none of the parties had confidence in the former regional power – Russia. Iran’s mediation efforts failed when a day after a ceasefire was signed in Tehran, Armenian forces captured the Karabakh city of Shusha (Shushi) populated by the Azerbaijani majority.

Thus, the CSCE, as an authoritative European organization, decided to seize the initiative. In March 1992, a large conference was convened in Rome, which was attended by Azerbaijani and Armenian diplomats, as well as representatives of the unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR). It was in Rome on March 24, 1992, that it was decided to convene an international conference on the settlement of the Karabakh conflict in Minsk, which was then considered the informal capital of the CIS. To prepare for the conference, the Minsk Group, which included 11 states, was created.

It is noteworthy that many experts do not know that the Minsk Group does not only include Russia, France, and the USA – it also consists of Turkey, Germany, Italy and others.

Initially, Russia reacted to the European initiative with jealousy, as it believed (and continues to believe, by the way) that only it has the right to resolve all conflicts and disputes in the post-Soviet space. Moscow’s attitude towards the Minsk Group is clear from the words of the head of the Russian mediation mission on Karabakh, Vladimir Kazimirov:

“Many perceive the Minsk Group as a kind of given. Few people know about its origin and the extent of its legitimacy. They don’t know that there was no decision in the CSCE to establish the Minsk Group… It was only about one emergency meeting, not a series, and even less about the regular functioning of a new auxiliary structure of the CSCE. That is why the Minsk Group has no mandate (unlike any other CSCE structure, even a temporary one). Some people talk about the mandate of the Minsk Group in a general way, without even realizing that it does not exist at all”.

The conference in Minsk in 1992 was never convened. There were many reasons for this. In my opinion, the main reason was that in the summer of 1992 the Azerbaijani side went on the offensive and captured a large territory in the north of Karabakh. Thus, the CSCE decided to establish the institution of the Minsk Group co-chairs in order to carry on exercising shuttle diplomacy in the region. The efforts of the first chairman of this group, the Italian diplomat Mario Raffaelli (known for his success in resolving the conflict in Mozambique), were unsuccessful.

At the same time, in the spring of 1994, Russia, without the OSCE Minsk Group, single-handedly managed to bring the parties to the negotiating table and achieve the signing of a trilateral ceasefire agreement (with the participation of the NKR).

Then came the “finest hour” of the Minsk Group. Regular trips have begun along the route Yerevan-Stepanakert/Khankendi-Baku. Sometimes meetings were convened abroad, sometimes it seemed that the parties were quite close to an agreement, as was the case in the American Key West, but in the end, everything was limited to traditional calls for peace and dialogue.

In both societies, they were already making fun of these co-chairs: “Oh, here they came again, probably craving some shish kebab, sturgeon and cognac”. Former Azerbaijani Foreign Minister Elmar Mammadyarov, in a recent interview, gave an example of this impotence. “An interesting incident occurred when I once again told the co-chairs that everything would end in a crisis, and one of them exclaimed: “Create a crisis so that we get off the ground”. The co-chairs understood that they were at an impasse”.

Throughout 30 years of activity under the auspices of the Minsk Group, not a single joint document has been signed by the heads of the conflicting states.

With Russia, the opposite is true. All the documents that the parties signed were done so with the assistance of the Russians (the Tehran agreement of 1992 is not taken into account, it did not last even one day). These include the Bishkek Protocol and the Ceasefire Agreement of May 1994, the Meiendorf Declaration of November 2008, the Trilateral Ceasefire Declaration of November 2020 and the Joint Statement on the Unblocking of Transport Communications of January 2021.

Of course, Russia is not going to give up the initiative and give up its leading role in resolving the conflict in the near future. However, given the fact that Russia is rapidly losing its international authority after the invasion of Ukraine, the parties need an alternative to balance. Since the Minsk Group is gone, the European Council could take its place.

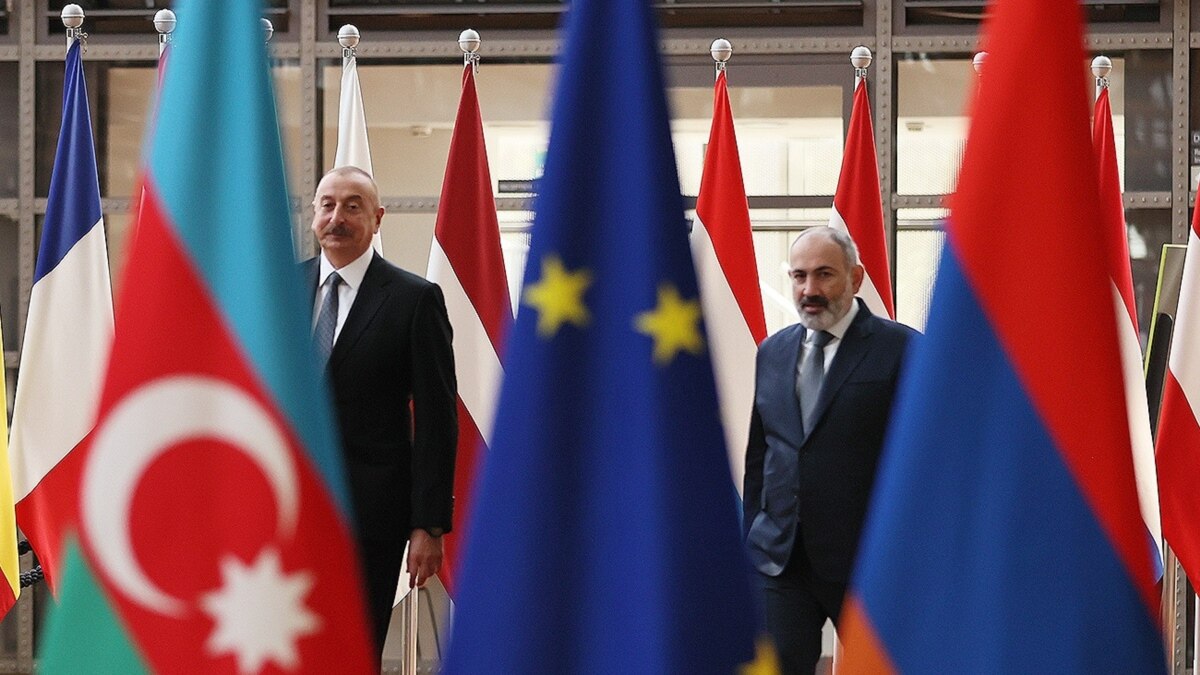

It seems that both Armenia and Azerbaijan are quite satisfied with the two rounds of negotiations under the auspices of the EU, mediated by the Belgian diplomat and President of the European Council Charles Michel. The elected representatives of the Karabakh Armenians will be sharply dissatisfied with this turn of events since the Minsk Group was the only place where they had a tribune. Now their voice can reach an international audience only through the media or through unofficial channels.

There are other formats for continuing negotiations. For example, the 3 + 3 format, that is, three countries of the South Caucasus plus Russia, Turkey and Iran. This format is interesting, first of all, because of the East-West and North-South transport corridors.

But still, it seems to me that the most effective format is bilateral meetings without intermediaries – Armenia-Turkey, Azerbaijan-Armenia, and ideally between Karabakh Armenians and Karabakh Azeris.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union