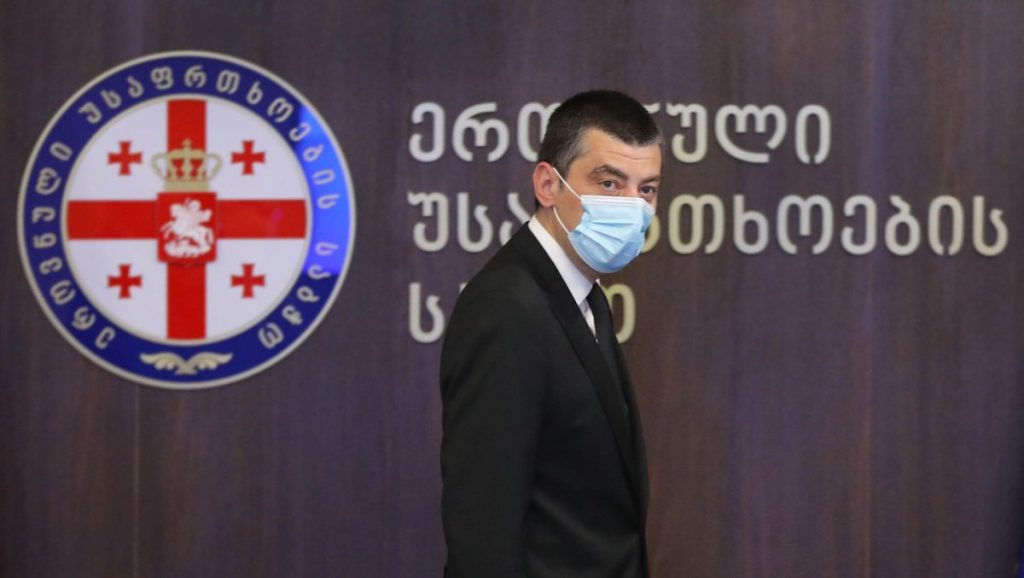

Op-ed: what to make of the resignation of the Georgian PM

Georgian Prime Minister of Georgia Giorgi Gakharia resigned on February 18 unexpectedly.As Gakharia explained, one of the main reasons for his resignation was his disagreement with the decision to arrest the leader of the opposition party Nika Melia, which caused him to have “disagreements with the team.”

On the same day, by the decision of the political council of the ruling Georgian Dream party, Defense Minister Irakli Garibashvili, who had already served as prime minister in 2013-2015, was nominated for the post of Prime Minister of Georgia.

Georgian political scientist Ghia Nodia analyzes what all this means for the country.

Rumors of Prime Minister Giorgi Gakharia’s pending resignation had been circulating for quite some time, but the way it happened became a sensation.

This was the fourth such resignation since Bidzina Ivanishvili, the founder of the Georgian Dream (GD) party and the first head of its government, ostensibly left politics in November 2013. But this is the first time when the resignation was related to a specific and hot political issue.

Irakli Garibashvili and Mamuka Bakhtadze did not really explain why they were leaving, while Giorgi Kvirikashvili referred to disagreements on economic policy issues without saying anything in particular.

As to Gakharia, he openly disagreed with an attempt to arrest Nika Melia, the leader of the opposition, this being the most important issue of the last period. On this, he was alone in his political team.

A couple of days before, GD representation in Parliament unanimously voted to strip Melia of his parliamentary immunity thus giving a green light to his arrest. Different GD public faces reiterated, why the government could not make any concessions on this issue.

There were no signs of any disagreement on this within the ruling party. Gakharia’s statement came out of the blue.

Coming from him this step was paradoxical in at least two ways.

Gakharia’s political profile was defined by the so-called “Gavrilov night”, when he, as the minister of internal affairs, led an operation to disperse a protest rally.

Critics alleged that police response was inexcusably heavy-handed. As a result of rubber bullets being used, two protesters lost their eyes. It was due to events of that night that a criminal case was opened against Nika Melia; he was to be arrested now due to the way this case developed.

That night became a turning point of sorts: the government started taking much tougher measures against the opposition and civic activists.

Gakharia became a symbol of this new policy. When in September, despite rallies demanding his resignation, Gakharia was promoted to prime minister’s position, everybody considered this another expression of the harder line.

And now, Gakharia happened to be the only GD leader who, on the very morning of Melia’s expected arrest, says this was a mistake and resigned.

The situation appears puzzling in another way as well. Gakharia was not just another political leader.

According to Georgia’s Constitution, he was the head of the executive, effectively, the leader of the country. The ministry of internal affairs also answered to him. If he did not think Melia’s arrest was right, he could have done something about it. But he just resigned in protest.

This shows that even before, he did not have powers that the Constitution ascribes to the prime minister. However, we had already known that prime-ministers are not in charge in this country. They are expendable technical managers.

Gakharia’s political weakness was further underscored by the fact that when Ivanishvili resigned from his position of GD chairman this January, his position was taken not by the prime minister, as it had been the case with Garibashvili and Kvirikashvili, but by Irakli Kobakhidze.

This boosted expectations of his pending departure. Kobakhidze was the person who voiced the government position most often, with Gakharia staying in the background.

It is always difficult to judge motives for personal decisions. But it is only natural that there will be lots of speculations on true reasons for Gakharia’s move. Many will find it difficult to believe that he suddenly became so soft-hearted.

The most probably bottom-line is that he, as his predecessors before him, lost Bidzina Ivanishvili’s trust.

We can already see a regularity here: under his informal leadership, prime-ministers do not last long. Giorgi Kvirikashvili is still the highest achiever: he stayed for two years and five months. Gakharia failed to make it to the year and a half mark.

However, the decision to slam the door and state disagreement on a critically important decision was his.

What did that mean? If he has independent political ambitions, that was the way to leave. But this is not the only possible explanation.

Maybe he just could not take it anymore and wanted to make a dignified exit. Moreover, he might have wanted to at least partially offset his reputation defined by an episode when people lost their eyes from rubber bullets.

It is of a much greater consequence what we should expect from the GD after this. The experience teaches us that in Ivanishvili’s team, the prime minister’s persona is not too important; however, Irakli Garibashvili’s comeback is notable in two ways.

This is an individual who has proven his full personal loyalty to Ivanishvili after being unceremoniously dismissed from the position of the prime minister; moreover, he is the favorite of anti-liberal, anti-western forces.

This choice makes one think that GD plans to continue the hard line against the opposition and civic activists.

Even though western politicians criticized plans to arrest Melia in no uncertain terms, so far GD leaders (possibly, save for Mr. Gakharia) did not pay much attention.

The government appears to refer to the western opinion only when it coincides with its interest.

However, Gakharia’s scandalous resignation may stimulate greater involvement of the democratic international community; it may try, once again, to instill a modicum of greater rationality in the Georgian political process.

The alternative is even greater polarization and uncertainty, or more of politically minded repression.

Ghia Nodia, the head of the Caucasus institute for Peace, Democracy and Development