My German house in Georgia

Germans in Georgia, Katharinenfeld/Bolnisi

There is a town 64 kilometers away from Tbilisi, which once used to bear the German name “Katharinenfeld”. It’s one of those residential areas built by German colonists who settled in the Caucasus in the period of Tsarist Russia. Germans no longer live there – Stalin exiled them in 1941.

Today, a unique 200-year-old architecture, that has been preserved in this small, once European town, is at risk of disappearing. In 2018, Bolnisi will mark the 201th anniversary of the German settlement.

The author of this article, Mariko Tsikoridze herself lives in a German-built house in Bolnisi. She shares her German “ancestors’ ” story:

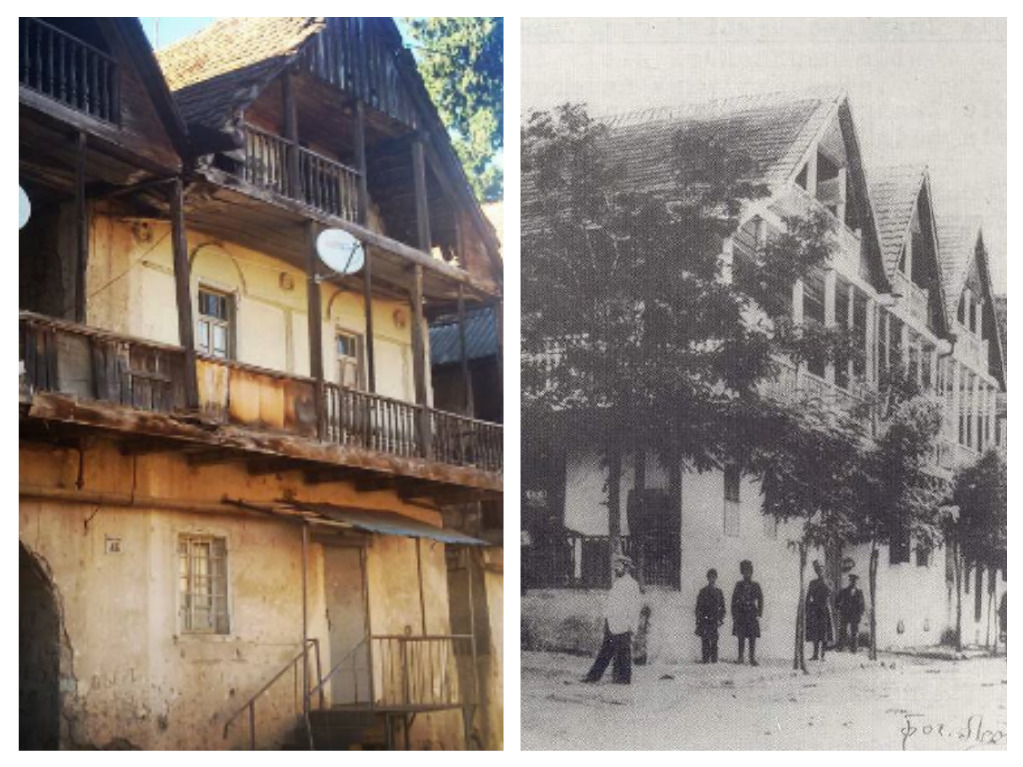

My German house is located in the center of Bolnisi, in the place where a former Lutheran church, Kirche, links to a broad, stone-paved road with lined-up houses with grand balconies, right in the first corner.

Otto Franc, a drugstore owner, used to reside in my house from 1921-1941. Otto’s mother, Gretta Walker, was a well-known pharmacist and physician in Katharinenfeld at that time.

My grandfather frequently recalled that in 1941, when the Germans were exiled by order of Stalin one autumn night and Georgian families were resettled in their houses, unlike other houses, where barrels full of German ham were found in the cellars, there were rows of glass flasks in our cellar.

The Franc family’s chemistry flasks are still preserved in our family, though they have another function nowadays -my father keeps Christmas drinks in them, with due observance of all rules and German rituals.

Apart from those flasks, there is also a German-language inscription that tells about Otto Franc’s house: ‘Hause Otto Franc, 1821’.

Numerous German traces could be found in Bolnisi outside my house, too. There is a 13-kilometer walnut alley at the city entrance, surrounded by tilled arable lands that are as smooth as a hand palm. This alley is our German legacy.

Württemberg Swabians (German: Schwaben; Swabia/Schwabia, a historic region in Southwestern Germany), created my town’s unique history.

People of the Queen of Württemberg

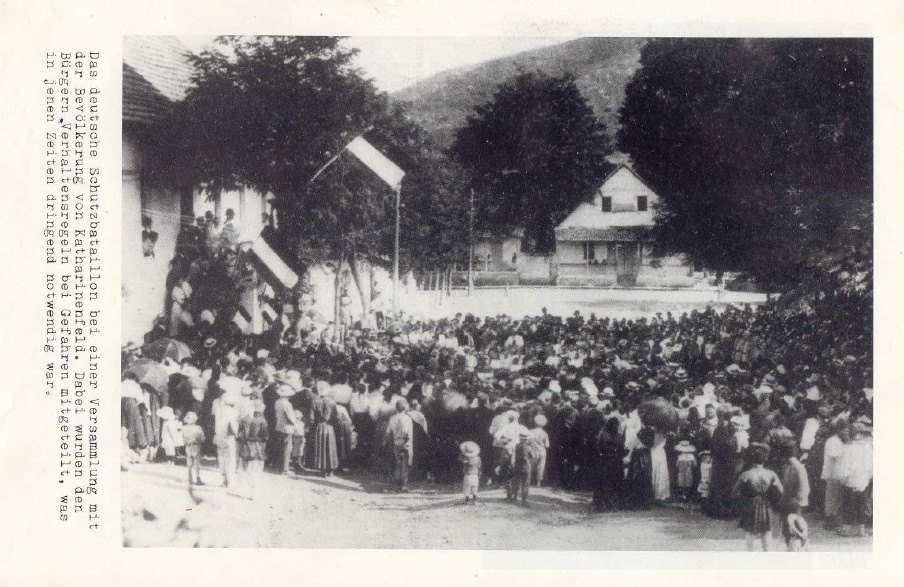

This story dates back to 1817, when Alexander I issued a manifesto, inviting colonists from Germany, that was on the brink of famine as a result of continues wars in the South Caucasus, to settle in Kvemo Kartli region.

A total of 15,000 families settled in the area, including 1,600 of them in Katharinenfeld (present-day Bolnisi). They enjoyed religious freedom and were exempt from taxes.

This settlement was named Katharinenfeld in honor of Katharina (or Catharina), the Queen of Württemberg.

Judging from the archive photos and Bolnisi residents’ stories, this area turned, within a decade, into a European city that had no analogue elsewhere in Georgia.

German colonists brought along with them great knowledge and experience. As far as I could remember from what my grandfather told me, there were well-maintained roads and sidewalks in Bolnisi. Germans kept numerous livestock, but one wouldn’t see a single cow wandering in the street.

In addition to cattle breeding and agriculture, the Germans soon constructed mills and wine factory buildings that are still operating nowadays. They had a gymnasium (grammar school), a wind band and even 4 football teams.

Sundays accompanied by accordion

Ira Dobrovolskaya, 84, is my neighbor. Of all the people, she’s the one who best remembers the ‘German houses’ and ‘German gymnasium’, where she studied herself.

Ms. Ira now walks with a pair of crutches. She carefully takes a heap of magazines from an old German ‘chiffonnier’ drawer. ‘Die Kaukasische Zeitung’- reads an inscription in bold yellow letters on a faded cover.

Those magazines compiled the Caucasus Germans’ stories and Ms. Ira received them from Stuttgart on a monthly basis, up until 2002. The magazine was published by the Germans, whose ancestors had lived in Bolnisi until 1941.

They set up the Caucasus Germans’ community in Stuttgart. It was with the assistance of that very community, that Ernst Allmendinger published his book, entitled: “Katharinenfeld, a German village in the Caucasus (German: “Katharinenfeld: ein deutsches Dorf im Kaukasus), which he dedicated to his ancestors.

In 1992, Bolnisi Germans were invited to Stuttgart to attend the community’s opening ceremony. Since then, each German family in Bolnisi was sent a copy of ‘Die Kaukasische Zeitung’ magazine.

Ms. Ira had draped a red-rose plaid blanket around her shoulders, made herself comfortable in a sling chair on a lengthy, German-style circle balcony, made of old oak and pine tree logs, and started sharing her story:

“I particularly remember Sundays. There was a good musician, Alexander Reitenbach, who would come out on the balcony and start playing his accordion. He lived in the vicinity of the park.

So, as soon as we, the children, heard the sounds of his accordion, we would immediately rush to the park. I also remember women in beautiful dresses, walking around with white baskets full of warm Zucherkuchen (German sugar cakes). Indeed, it was a small European city.”

Children were crying and dogs were barking

Yulia Fehringer, 82, recalls the autumn night when her grandparents and her uncle disappeared.

“Even today, I get scared at hearing a door knock. The sounds of dog barking, children crying and cattle moaning, all mixed together. I was a little child then and I couldn’t understand why everyone around me was crying.

I couldn’t understand the reason, why the entire Katharinenfeld deserted within an hour, why we had stayed and they had gone. Tables laid for dinner in some of the houses remained untouched. It was the night of torture that I’ve been trying in vain to erase out off my memory all my life.”

Yulia Fehringer’s family wasn’t sent to exile, because her German father was married to a local. Yulia’s mother was a daughter of a local merchant of Armenian descent.

Soviet reprisals against German colonists started in the 1930s. 600 Germans were exiled to Karelia in 1935. 325 Germans were arrested the same year in Bolnisi, also referred to as Luxemburg (Katharinenfeld was renamed into Rosa Luxemburg in the 1920s, following the Red Army invasion of Georgia).

Later they were either exiled or executed. In 1941, when WWII broke out, all Caucasus Germans were exiled either to Kazakhstan or Siberia, since Stalin feared that they could have formed the fifth column.

Afterwards, it was ordered to erase any trace of the Germans’ presence in Bolnisi. The German architecture of the buildings were reshaped, German-style balconies were deformed; the German cemetery was leveled to the ground. There is a memorial in honor of the German colonists in that place now.

Leikuchen and Zukerkuchen

However, it has turned out that traces of the Germans couldn’t be erased that easily in Bolnisi, albeit to a lesser extent – though it can still be sensed not only in the architecture, but also in Bolnisi residents’ customs and traditions.

For example, people in Bolnisi still bake Leikhuchen and Zukerkuchen, the sweet treats that Germans traditionally cook for Easter and Christmas.

The Center of German Culture has been functioning in Bolnisi for over a decade. Every Easter is celebrated in the Center by baking Leikuchen, a traditional German Easter cake. Thus, the Center helps to further promote the old German tradition.

Liana Taranova’s mother was German. Therefore, she knows the sweet treat recipe better than anyone else. She even had some trainees, local young ladies, whom she taught baking skills.

“Every Sunday morning started with a portion of dumpling soup. Then, all German families gathered for mass in the major Lutheran Cathedral. The Germans knew the true worth of both, labor and entertainment.

Therefore, every holiday here was always a special event, with an orchestra playing non-stop,” recalls Liana Taranova, whose mother was a German colonist teacher, Bertha Johannes Muhrer.

Liana’s mother wasn’t exiled in communist times, because her husband was Russian and he was allowed to stay there with his family. However, part of their house was seized and only 2 rooms were left for them.

Despite their appeal, Liana and her sister, Gita, were not restituted the seized part of the house after the communist rule either. But they have another goal now: if reconstruction of the German neighborhood in Bolnisi is launched, maybe it will be possible to restore the Lutheran Kirche (Lutheran church), which currently accommodates a sports complex.

New Bolnisi

There are only 300 houses in the German neighborhood in Bolnisi and only 156 of them have maintained their original appearance.

In 2015, the Georgian Culture Ministry launched the first stage of the German heritage inventory project. 12 Buildings in Bolnisi were conferred the cultural heritage status as part of the project.

Swabian architecture is on the verge of destruction nowadays. Houses become dilapidated from age, there are cracks all over and there is water coming down from attics.

In fact, such houses couldn’t be found in many other parts of Georgia. Germans used to build very practical houses, with two-storey basements and unique attics. The basements were constructed so that they were always 12-140C all the year round. 200-Year old barrels are still preserved in the basements in some of the houses.

There were built-in oval stoves. The smoke coming from the stove also did its job: it went up to the attic, where pork pieces were smoked. Germans made a very unique smoked ham.

Each house attic here had a triangle-shape pigeon loft. As far as I was told, the Germans not only smoked ham there, but they also dried cheese to prevent the appearance of worms. Every house in this area had an attic pigeon loft.

The issue of rehabilitating the German neighborhood in Bolnisi becomes particularly acute and is raised by Bolnisi residents every 4 years, during the elections. The politicians are also lavish with promises, but there has been no progress in this matter. On the contrary, it is retrogressing in course of time.

In fact, this town, which is just 64 kilometers away from Tbilisi, could become a very attractive place for visitors. This, in turn, could bring economic benefits to the locals.

According to the latest population census conducted in 2014, the Bolnisi population comprises of 8,967 people, as compared to 15,047 people in 1989. Unemployment, social problems and poverty could be observed here at every corner, like elsewhere in Georgia. Young people more frequently leave Bolnisi in search of jobs nowadays.

Bolnisi residents pinned their hopes on the premise that some German foundation would get interested in the rehabilitation of Bolnisi as ‘the largest German settlement in the Caucasus’. However, neither have the Germans shown any interest in it so far, nor has it been included in the state-run historical districts rehabilitation program.

According to Konstantine Kordzadze, the Head of Bolnisi Municipality Infrastructure and Public Amenities Service, local government funds will hardly suffice for the reconstruction of the town.

“This time we are going to apply to the Cartu Fund (the charity foundation, set up by ex-Premier, Bidzina Ivanishvili). We are preparing all necessary documents and the project outline, that we are going to submit to Cartu Fund end of May.

Though, it won’t be a full-fledged reconstruction project. The government’s involvement is required in order to carry out comprehensive rehabilitation works and make Bolnisi attractive for tourists,” says Kordzadze.

Bolnisi is going to mark the 200th anniversary of the German settlement in October. According to local municipality officials, some major events are planned to be held.

Equipped with photo cameras and cell phones, the guests are expected to take photos in the German part of Bolnisi. Perhaps they will capture my house, too.