Misinformation in the Karabakh conflict: analysis of Azerbaijani media from Armenia

Fake news in Azerbaijan regarding the Karabakh conflict and Armenia

Analysis of disinformation spread in the media in Azerbaijan regarding the Karabakh conflict and Armenia. The study was conducted by Samvel Martirosyan, Yerevan, Armenia.

A similar study by an Azerbaijani author can be found here

About the study

Ever since the launch of the Armenian and Azerbaijani conflict in the early 1990s, it has stood out by the fact that the military conflict was accompanied by information war, partly consisting of the creation and dissemination of disinformation.

Both parties have been and continue to be involved in these processes, even though the tools and the campaigns deployed by them are different.

The aim of this study is to propose methods of checking information in the conditions of a huge mass of fake messages. Researchers in Yerevan and Baku have made use of various methods of fact checking and have studied a few series of fibs, that contained various elements of disinformation.

Cases related to three serious military escalations have been selected as examples, namely the escalation along the contact line in the unrecognized Nagorno Karabakh Republic in April 2016, the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan in July 2020, and the second Karabakh war from September 27 to November 10, 2020.

In all cases, and especially in the autumn of 2020, major hostilities leading to a high toll for either party took place. All these events were accompanied by an intense information war.

Research shows that the fake news published during fierce battles is often created deliberately by the state propaganda machine. Besides, they are often authored by journalists who confuse their profession with that of propagandists. There may also be cases when it is hard to clearly identify the source of the disinformation and there is a probability that it is caused simply by Chinese whispers.

As of now, the main channels of disseminating fake news have been social networks. However, they are also the best platform to find means and assistance to debunk manipulative materials. The online community may often help the researcher in finding the necessary sources and send the necessary photos and videos. Such assistance becomes an important aid to the researcher and an addition to the set of technical means, applied by the researcher.

In the course of this study, methods of text, photo, and video recognition were used, the latter being especially important, since modern fake news mainly comes in multimedia formats.

Many experts consider that the second Karabakh war of the 2020 fall unprecedented in terms of the scale of propaganda attacks in the cyberspace. Fake news appeared in such volumes that it was difficult to tell them from real military reports.

Research reports, compiled by authors from Baku and Yerevan, use the terminology and toponymy chosen by the authors.

A view from Armenia

Background

The Karabakh war is an armed conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijani that took place in the territory of the former Nagorno-Karabakh autonomous region in Azerbaijan and its adjacent territories in 1991 – 1994. The war was concluded with the signing of a ceasefire agreement, however skirmishes continued from time to time.

As a result of that war, the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region of Azerbaijan and the seven regions surrounding it came under the control of the Armenian forces. The Azerbaijani population was forced to leave these territories.

The Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (NKR), created on the site of the Azerbaijani autonomy, was not recognized by any state in the world, including Armenia. Negotiations on a settlement of the conflict with international mediation yielded no results.

The first outbreak of full-scale hostilities after the events in the early 1990s occurred on April 2-6, 2016 and it went down in history as the “April War” or “four-day war.” The events took place on the line of contact in the Karabakh conflict zone.

In July 2020, there were clashes on the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The full-scale hostilities from September 27 to November 10, 2020 went down in history as the “second Karabakh war.” During this time, both parties had a toll of at least eight thousand, with the search for the missing underway at the time of this publication.

The ceasefire arrangement included the following major points: returning control over several regions adjacent to Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan; deploying Russian peacekeepers in the region and withdrawal of the Armenian military; exchanging prisoners of war and ensuring the return of refugees.

From the very first days on, an information war was being waged over Karabakh, too. Various methods of propaganda and counter-propaganda were applied by on both parties.

At the beginning of the conflict, this was often done on the spot and ad hoc, with no prior preparation. Later, after the war, with the development of the Internet, the conflict grew onto a new level with the formation of ‘guerrilla troops’ of cyber activists who waged fierce wars in the cyber fora.

The first major cyberattacks with the involvement of Armenian and Azerbaijani hackers were recorded already in the early 2000s. The first serious duel between the Armenian hacker group Liazor and the Azerbaijani Greene Revenge unfolded at the beginning of 2000, which temporarily disabled almost all websites in both countries (however, the Internet was not particularly developed then).

The casus belli was a website created by the Armenian diaspora representatives and disseminating objectionable information, discrediting Azerbaijani authorities.

But back then hackers and propagandists emerged on their own and were not controlled by anyone. The development of technology and the enhanced role of the state in the conflict led to a point where both parties now had special bodies for information security, propaganda and counter-propaganda.

In Azerbaijan, the building of state propaganda machine began at the beginning of the 2000s. Initially the Armenian authorities did not take this matter seriously, but the concept of information security was adopted already in 2009.

In the recent years, the two countries have displayed different approaches to information warfare.

Azerbaijan started building a top-down command structure, the guerrilla groups gradually left the scene, and the media channels in the country were almost completely taken control of. This resulted in a well-controlled and efficiently operating model which was guided mostly by the Soviet structure.

In Armenia, they chose the hybrid model, which offers the integration of state-owned structures and free groups into a single network, which covered the whole of the information realm and media space.

The hostilities in the Karabakh conflict zone in April 2016 and the clashes at the Armenian-Azerbaijani border in Tavush region in July 2020 showed the operation styles of both models.

The Tavush clashes came as a big surprise, since significant and fierce clashes never happened on the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, with the main tension always concentrating along the line of military contact in the Karabakh conflict zone.

However, clashes between combat units, which actually lasted for more than a week, immediately led to a sharp increase in the intensity of information warfare, during which both hacker attacks and propaganda methods were used.

Also, a fairly large amount of fake information appeared in the internet. Disinformation spread through all possible channels – from media to social networks, from Facebook and Instagram to Twitter and WhatsApp groups.

Despite the quantitative and qualitative variety and ample volumes of manipulative information, the information war was unleashed much earlier, and an active use of social networks was observed back in the 2016 April clashes.

The April hostilities started on the night of April 2, 2016, and lasted about 4 days in the active phase, although the situation continued to be tense until the end of April with clashes claiming a total of several hundred lives.

The events began with a surprise attack of the Azerbaijani troops in the northern and southern directions onto the border posts of the Karabakh troops. By the morning, active clashes were taking place along the entire line of contact with the use of all types of troops.

The Azerbaijani top-down management misfired already on the very first day of the escalation. The information realm reacted in the following manner – the Azerbaijani press did not report anything at all until noon, whereas in Armenia reports on the outbreak of hostilities were already published.

Apparently, the top-down, clear-cut relations were the hindrance to the coverage of the situation by the Azerbaijani press, and the military did not know how to describe the developments that deviated from the original plan.

However, already by the end of the day, both parties got things going, and a real information war unfolded in all directions.

In fact, the parties use all possible means of information. Cyberattacks are launched by both parties. Armenian and Azerbaijani news and official websites are constantly under pressure due to DDoS attacks (a Turkish hacker group came to the Azerbaijani party’s aid in one of the attacks).

Propaganda materials are thrown into circulation via the press. Just imagine this – a letter by the NKR Defense Minister to his colleague from Armenia, allegedly intercepted by intelligence, is published in the press. The text was written with terrible mistakes a child would make. But it may prove handy when used domestically. (The data, relevant to this case, will be considered further in detail).

The war seems to be most active on social networks, since almost everyone is involved in them. Here anyone can find a task and an audience to the best of their abilities and availability.

The most cunning ones (and perhaps the ones who are working for special services) try to gain the users’ trust by using Armenian names and making inquiries about the situation on the front, in Yerevan and Stepanakert, to find out if there is any panic, where the troops are heading, etc.

Or else, they create panic, referring to their acquaintances at the front, who definitely saw it with their own eyes that “all is lost.”

Some argue in the comments to published articles. Others share articles themselves, passing them onto friends in other countries.

But the largest group consists of those who swear. They swear as much as they can, in whatever language they can, and even if they do not know a language, they use Google translate and still swear.

Application of information struggle methods in all directions has been a component that constantly accompanied the Karabakh conflict in the recent years.

However, the hostilities of recent years have brought the confrontation to a new level, turning it into a real information war, which can seriously affect the events at the front.

The involvement of both societies in the information confrontation on such a scale is truly a new development. And it will show results in the future.

The politicians will have to face the fact that they have involved their citizens in an active confrontation in the information domain.

And it is hard to dismiss and send regular citizens back to the barracks, unlike soldiers.

During the hostilities in April 2016

Fake seizure of Talish village during the escalation in April 2016

The Azerbaijani TV company ANS TV released a short and staged report on April 8, 2016.

In the foreground was the agency’s correspondent who reported that he was on the road leading to the village of Talish. In the background, a serviceman of the Azerbaijani armed forces was setting up a border post with an inscription in Azerbaijani – Agdere region, Talish village.

To understand the situation, the village of Talish is located in the territory of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. This is one of the few settlements that are close to the contact zone between the Azerbaijani and Karabakh forces.

According to the administrative-territorial division, the region in which the village is located is called Mardakert in Karabakh. The ANSPRESS TV commercial used the expression “Agdere region”.

In Azerbaijan, the city of Mardakert is called Agdere. According to the administrative-territorial division of Azerbaijan, which also includes the territory of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, this region is called Terter, and nominally includes both the Martakert region of the NKR and part of the territory of present-day Azerbaijan.

Before the 1990 Karabakh war, the territory of the Mardakert region was indeed called the Agdere region, but this name was abolished by the Karabakh authorities back in 1992.

The video raised suspicions for several reasons:

1. It was too short for such an important event, namely it was only 23 seconds long.

2. The functionality of leaving comments on the video on YouTube was turned off, which accordingly reduced the chances of receiving information from users who might have information about the place.

3. The complete absence of any background that would at least approximately resemble a settlement which could in any way suggest that the village was taken under control or the troops had come close to it.

4. The Talish village is located in a lowland, is surrounded by hills, with Armenian and Azerbaijani posts situated on them. This can clearly be seen using Google Earth, which enables a 3D terrain view of the location.

Even if the village itself was not taken, and the Azerbaijani military controlled only the main heights, the ANS TV correspondent could easily and safely stand against the background of the village, at least at some distance. However, we see that there is a hill behind the journalist and the soldier sticking a pillar in the ground:

This, most probably, suggests that it is located significantly northeast of Talish, far from the hills.

These factors, as well as the absence of continued reports about Talish, suggested directly that the topic was invented solely for propaganda purposes and had nothing to do with real facts as it was later proved by the real course of events.

Karabakh Army commander Levon Mnatsakanyan’s fake letter

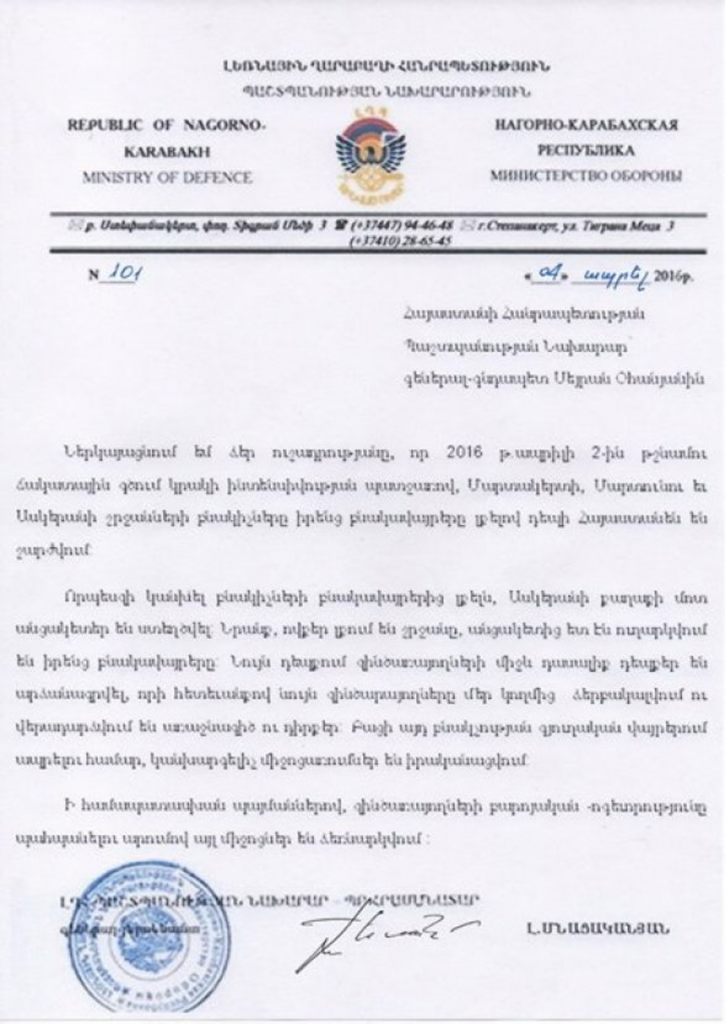

On April 4, 2016, a fake letter on behalf of the Minister of Defense of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic Levon Mnatsakanyan, addressed to the Minister of Defense of Armenia Seyran Ohanyan, appeared in the Azerbaijani medis.

Azeri newspaper haqqin.az published an article, under the headline The Karabakh Minister’s Letter Surfaces in Social Networks.

The article specifically read that a letter from NKR Defense Minister Levon Mnatsakanyan, addressed to the Armenian Defense Minister Seyran Ohanyan, had appeared in the Armenian social networks segment.

The article presented a scanned copy of an Armenian language letter, printed on letterhead, followed by this Russian translation of its content (preserving the spelling in the original copy):

“The letter reads that as a result of the escalation of the conflict, launched on the night of April 2, the residents of Askeran, Agdere and Khojavend regions are leaving their homes and heading for Yerevan.

To prevent the outflow of the population, checkpoints have been set up at the exit from the city of Askeran.

In addition, the “defense minister” of the “separatists complains about the falling morale of the soldiers and the increasing number of desertions. After the capture of the deserters, they are forcibly returned to their combat positions.”

“Preventive measures are being taken to stop the outflow of residents from the villages. Work is also underway to improve the morale of servicemen,” the letter reads.

It is noteworthy that the Armenian version contains Karabakh toponyms, namely referring to the regions of Martakert, Martuni and Askeran, but the editorial board considered the translation of the toponyms and the use of Azerbaijani toponymy important for ideological reasons).

This letter was actively circulated by the Azerbaijani media.

At first glance already, it is clear that the source does not stand any criticism, since even when shared on social networks, the journalist must provide at least a reference to the source, at least mentioning which social network the scanned copy of the letter was found on.

The letter itself is also obviously fake. The letterhead contains an error – the address of the Ministry of Defense of Nagorno-Karabakh is 13 Tigran Mets Street, Stepanakert. The one who authored the fake letter made a mistake and indicated 3 as the number of the building, omitting the “1” of “13”. The address can be found in the public domain, for example, in the Spyur database.

The text of the letter itself contains many spelling and stylistic errors, starting from the handwritten date, where a spelling error was made in the Armenian word for “April”.

The military in the post-Soviet space have been perceived as somehow illiterate ever since the Soviet times. But stylistic and spelling errors in the text indicate that it was written by a person who did not know the current bureaucratic Armenian language.

Liberation of the already free village of Chojukh Marjali

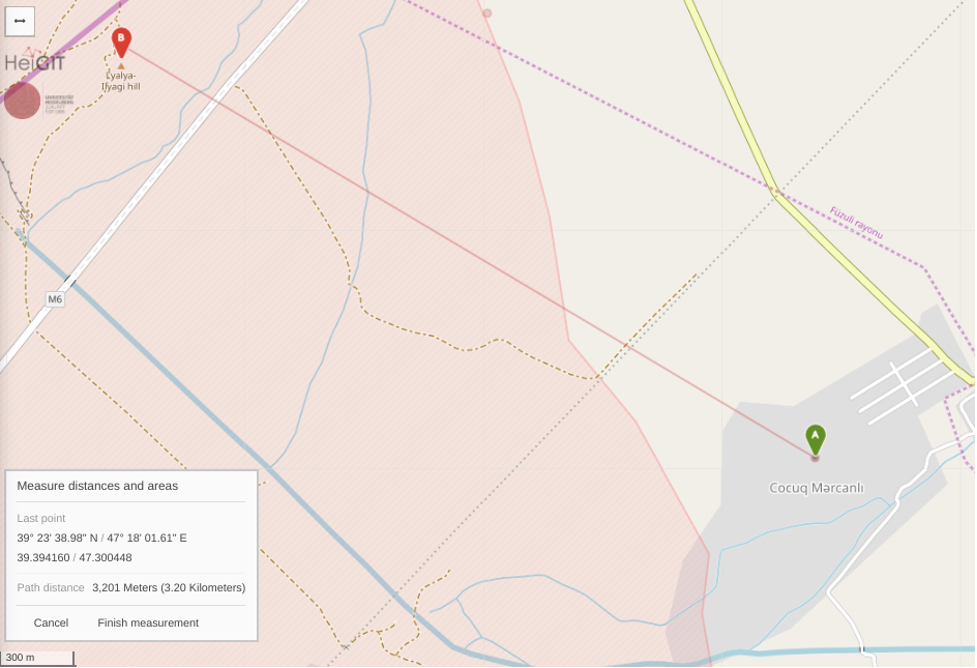

On April 7, 2016, the Azerbaijani media and social networks disseminated information that the country’s army had liberated the village of Chojukh Marjanli, which was occupied by the Karabakh army, and after 1994 only at that time could the villagers visit their graves of their families.

The fact-check showed that the village had never been under the control of the Karabakh army, and its residents had visited it before.

The most difficult thing in verifying this case was the name of the settlement. Due to the difficulties of transcription from the Azerbaijani language, the spelling is found in several versions in the press and on social networks. The settlement in Russian comes in many versions – Chojukh Marjanli, Jojuk Marjanli, Jojug Merjanli with a few other variants, and in the English transcription it comes as Cocuq Mərcanlı, Jojug Marjanli or Chojuk-Marjanly. It was necessary to use the full range of transcriptions, since various spelling variants were used on social networks, and even in the Azerbaijani press. Search on social networks made it possible to understand the general situation.

In reality, the situation was different from what was pictured in the report. The Azerbaijani troops occupied the Leletepe hill (Names vary – Lala Ilahi, Lala Ilahi Tapa, Lalatapa), which is located next to the contact line.

Given the distance between the hill, controlled by Karabakh troops until April 2016, and the village of Chojukh Marjanli, it must have been under fire, though not of small arms. In this regard, in the period after 1994, the Azerbaijani side simply did not begin to restore Chojukh Marjanli, which was destroyed during the hostilities during the Karabakh war. The village was actually left with no residents, who would only visited it from time to time.

Despite the reports of the Azerbaijani press, on social networks one can find a lot of evidence that the village was under the control of the Azerbaijani side and civilians periodically visited it. For example, a video made in 2012, and another one dating to 2013.

However, the theme of the alleged liberation of the village sustained even after the April events.

On January 24, 2017, a special order was issued by the President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev and published in the state news agency Azertac with the following headline: “Order of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan on Measures to Restore Chojukh Merjanli in Cebrail Region, Liberated from Occupation.“

The text of the order begins with this wording:

“Liberated from Armenian occupation due to the successful counter-offensive of the Azerbaijani army last April, Chojukh Merjanli village has become safe for people to live in.

Thus, in these territories, which have completely come under the control of the armed forces of Azerbaijan, conditions have been created for the start of total rehabilitation so that civilians who historically lived here could return home.”

As you can see, even at the highest level, the village of Chojukh Marjanli was mentioned as liberated from occupation a year after the April events.

Hostilities in Tavush, July 2020

Sending a fake text message (SMS)

Many disinformation materials were circulated during the clashes between the Armenian and Azerbaijani military on the Armenian border in the Tavush region.

The most serious case, however, was the text message sent to the Armenian citizens on behalf of the Armenian Ministry of Defense on the night of July 17, 2020. At night, about 3 thousand mobile network subscribers received a message from MIL.AM (this is the domain name of the Armenian Defense Ministry) with the following content:

“The situation on the front line is tense. The Armenian army is suffering heavy losses. Mobilization is announced to save our homeland. Those unable to serve in the army are requested to donate blood in the medical institutions.”

Later, it will become clear that the mass delivery of this text was caused by an Azerbaijani hacker attack that targeted an intermediary organization dealing with text message delivery. With the already hacked system, the texts were sent out, which was stopped a few minutes later, however, a few thousand people had already received it.

By the way, this happened at night, against the backdrop of anxiety for news from the frontline. Naturally, many began to share this text on the social networks, and early in the morning this was already the most discussed topic.

The only thing that gave out the fake in this case was the spelling in the message text.

The message was written in Latin alphabet – a fairly common practice in Armenia, since many phones do not recognize the Armenian alphabet, so in this case, the Latin alphabet was not a suspicious factor.

However, the transliteration used in the text did not reflect usual patterns.

In particular, the use of double ‘r’ in the text suggests that the author of the text did not know the Armenian pronunciation well enough, since no Armenian would ever use double ‘r’.

There are two letters and two [r] sounds in the Armenian language, the differences of which are rather difficult for tell by non-native speaker or do not know the language well. The problem is specifically the difference in spelling and pronunciation.

The use of the Latin letter “x” for other sounds is another specificity of transliteration. When switching from Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet, a similar change took place in the Azerbaijani language, too.

A number of other similar inaccuracies emphasized that the text was written by a person who did not speak Armenian well, although, apparently, could write in Armenian.

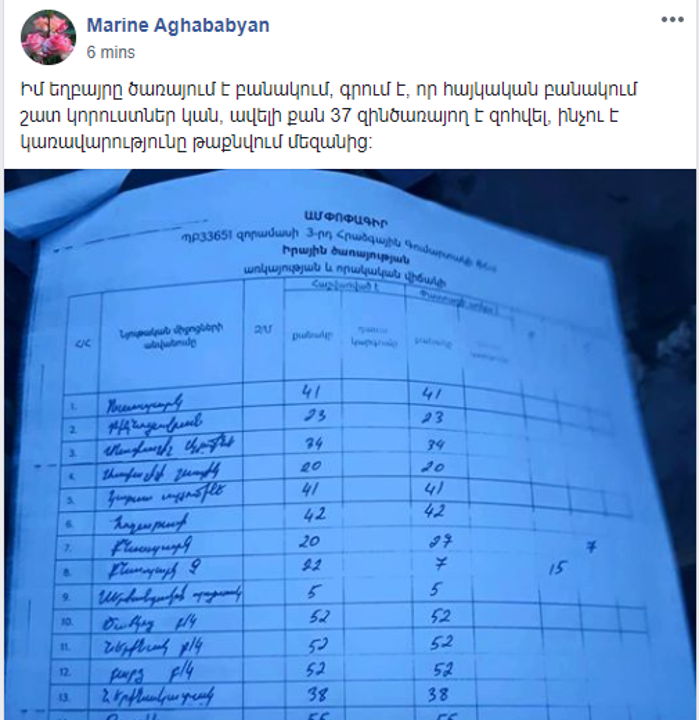

Messages from hacked Armenian social media accounts

During this period, disinformation was leaked through mainly hacked Facebook accounts, owned by Armenian users.

For example, user Marina Aghababyan wrote that her brother was serving in the army and had informed her that the Armenian military was incurring heavy losses – 37 killed. And she was asking why the government was hiding those figures from us.

As evidence, there is a telephone picture of the list of servicemen’s names.

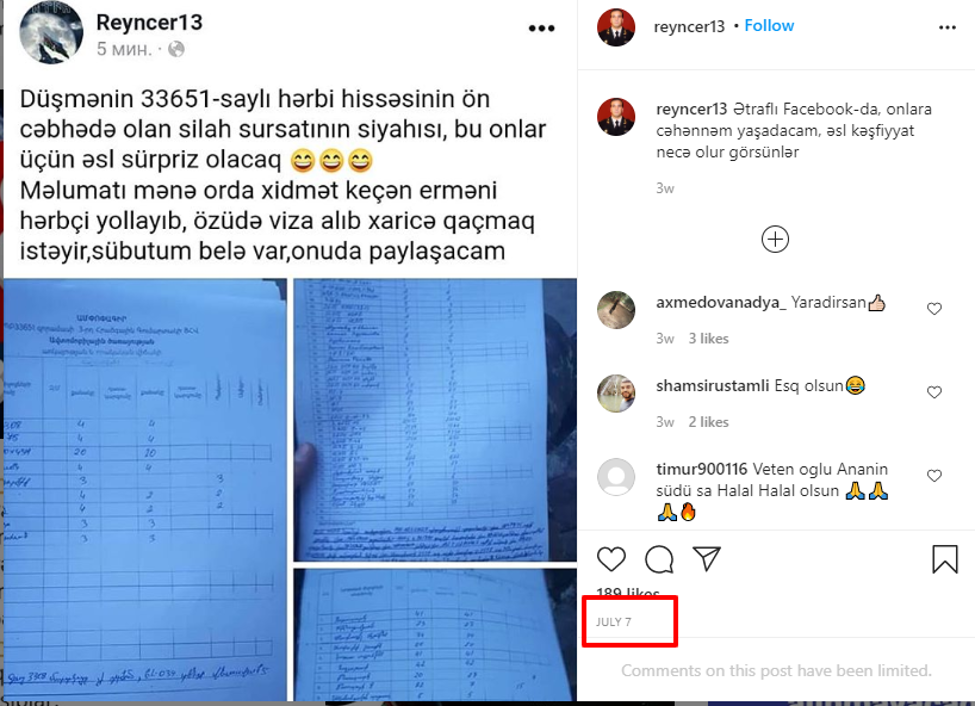

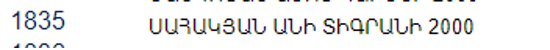

However, this photo had been posted on the network earlier. On July 7, five days before the start of clashes on the border, an Azerbaijani hacker group, named, Reyncer 13, had already published this photo, along with a few others.

Most probably, someone in the Armenian military had inadvertently photographed a number of documents in his military unit and sent it to someone through his personal email address.

The hacking of e-mail account had led to the open access publication of the document, which was later used to spread disinformation.

To further confirm the fact of using the hacked account, the method of crowdsourcing was used. The screenshot of the message disseminated on behalf of Marine Aghababyan was posted on Facebook.

Within 10 minutes, mutual friends were found who called on the phone to confirm the fact that her account was hacked and used by the hackers.

The fake protests of Armenian soldiers’ mothers

During the period of active hostilities at the border, on July 14, a material, more of a propaganda piece than journalism, was uploaded on the YouTube channel of the International Information Service of Azerbaijanis in Russia, run by journalist Fuad Abbasov.

The video was titled “The whole essence of the war in two frames! Azerbaijanis and Armenians react differently to the war!” The first part of the video shows some people in Azerbaijan in bellicose spirits, followed by some video from Armenia, showing the police using force against protestors.

Abbasov commented on this as follows: the video depicted the mothers of those soldiers who are forcibly sent to fight in Karabakh, and the mothers were protesting against it. The whole point of the video was to show that Armenians were afraid, that the mothers were protesting and the authorities had to forcefully mobilize the army.

However, the video came with sound, and one can clearly hear the cameraman saying that the police should not detain concrete individual demonstrators, because they are MPs. One of the shots presents Naira Zohrabyan, the head of the National Assembly’s Human Rights Commission, an MP from the opposition Prosperous Armenia Party, who is by no means a soldier’s mother.

A simple search using the keywords “arresting Naira Zohrabyan” in Armenian allows us to find original videos filmed a month before the events in Talish and made at the building of the National Security Service of Armenia during an opposition protest, after the leader of the Prosperous Armenia Party Gagik Tsarukyan was detained.

A strange video, released by the ministry of defense of Azerbaijan

In the morning after the outbreak of hostilities in Tavush, the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense uploaded a video on its official YouTube channel. According to an official status, posted onto the Ministry’s website, the video presents the results of the night battles.

The post’s description says:

“Units of the Azerbaijan Army struck an enemy strongpoint – VIDEO. In the night of July 13, tensions continued towards Tovu at the Azerbaijani-Armenian state border.

During night battles, our military units, using artillery, mortars and tanks with precise fire, destroyed the stronghold, artillery installations, vehicles and manpower in the territory of the enemy military unit.”

According to Youtube DataViewer, the video was uploaded to YouTube at 08:58 a.m. Baku time on July 13. The video clearly shows that the footage was taken in the daytime, the shadows can be clearly traced.

Even if we theoretically assume that the shadows could have been caused by the moonlight and the shooting was done with some super-sensitive camera, it should be borne in mind that on that day the Moon was shining at half its brightness, which can be checked using the WOlfram Alpha search engine, hence it could hardly create such contrasting light.

Most probably, the ministry of defense found some archival materials and rushed to publish them as fresh results from the hostilities.

The 2020 war

The war in Karabakh, unleashed on September 27 that lasted 44 days, was accompanied by an intensive dissemination of disinformation. Social networks in Armenia were the main source of dissemination of fake information. Unlike Azerbaijan, where practically all social networks were blocked during the war, only TikTok was partially blocked in Armenia.

Volunteers turned into refugees

On October 1, the Azerbaijani media began to actively disseminate a video, reporting that thousands of Armenians were fleeing from Karabakh. For example, Trend agency used the headline “Hundreds of cars with Armenians leaving the Nagorno-Karabakh Region in Azerbaijan (VIDEO).”

The report said, “The footage shows a queue of many kilometers of cars, heading towards Armenia. The video was filmed with a mobile phone camera by an eyewitness and was posted on Twitter.”

Similar headlines appeared on many news sites. For example, “Armenians are leaving Nagorno-Karabakh. The queue is several kilometers long.”

Two factors were notable here. When posted on the social media, no hyperlink to the original post was used, which is always one of the indications of a potentially fake information piece. Besides, the video had no sound, although it was clear that the video was taken not by the recording device in the car, but rather someone’s phone from within the car, which meant that the original came with sound.

This means that the editors could have deliberately removed the audio track, which is another indicator of faked content.

Indeed, a search using screenshots from the video proved effective, finding the video with the original sound. It was posted on Facebook, and the YouTube version of the video from Armenian news portal 24 News channel was available, too.

It became clear that the recording was at least 2 days older, and dated back to September 29th. The background conversation suggested that in fact the people in the car were talking about a reverse flow: these were volunteers going to Artsakh immediately after the hostilities were unleashed. And the only car traveling from Artsakh to Armenia was the one they filmed the queue from.

Fictional hackers “confirmed” the president’s words

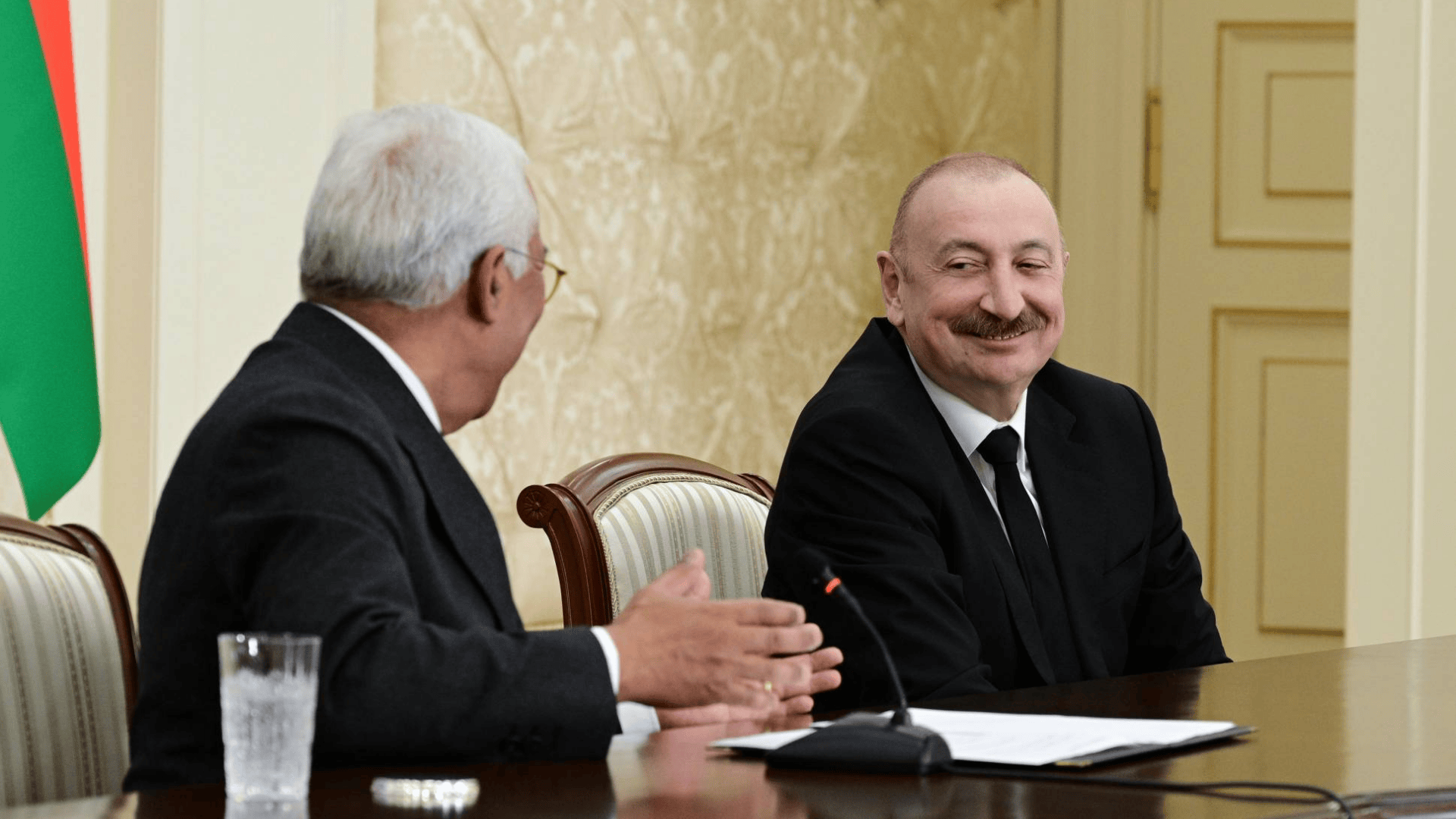

On October 28, the President of Azerbaijan gave an interview to the Russian news agency Interfax, stating:

“According to Azerbaijan’s data, the toll of the Armenian party during the hostilities in the zone of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict since September 27 amount to about 5 thousand, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev said.”

There was no independent confirmation of these words. But very quickly – on the same day – the Azeri media discovered that Azerbaijani hackers had allegedly broken into the Armenian Defense Ministry system and stolen a document containing the names of the killed Armenian servicemen.

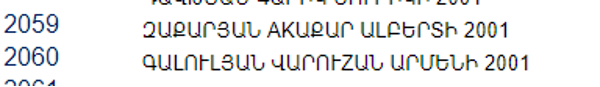

For credibility reasons, the list contained the names of those servicemen who were confirmed dead by the Artsakh Defense Army. However, the rest of the names manifested so many strange nuances that it became obvious that the list was fabricated from a variety of databases, containing data of the population, unrelated to military operations in any way.

So, for example, the list contained 17 entries with the female name Ani. There might, definitely be female contract soldiers among the killed. However, most of the Anis on the list were too young, for example, a certain Ani born in 2000, that is, of draft age.

Besides, the list contained 11 Liliths, 4 Larissas (one of them only19 years old), along with a few dozen Anns, Susans and Ruzannas, many of whom were 19-20 years old.

There are also many names containing Latin letters, which may indicate a failed scanning exercise of documents which were incorrectly deciphered during text recognition.

The names of three people came as acronyms, consisting of three consonants, among which a political party – Prosperous Armenia – could be identified.

To cut the long story short, the “hackers” filled out the list, using various lists of names and data they had at hand to “prove” Ilham Aliyev right.

Armenian-Colombian and Armenian-Serbian terrorists

Turkish propaganda, too, actively participated in the information war. Against the backdrop of documented reports that Syrian militants were fighting on the side of Azerbaijan, recruited and transported to the front by Turkish authorities, fake information appeared on Armenian ties with Kurdish terrorists.

On October 3, the Turkish CNN TÜRK released an article, reporting that Kurdish terrorists from the Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK), together with Armenians, were allegedly fighting in Artsakh, presenting photographs as evidence, allegedly depicting Armenian and Kurdish terrorists together.

In fact, this photograph shows the flag of the Colombian National Army (FARC).

The Armenian and Colombian flags are often confused, as they match in color, however in reverse order. For example, in 2016, an Azerbaijani official, in a fit of patriotism, broke the Colombian flag instead of the Armenian one.

Another example of an attempt to invent a story of mercenaries fighting on the Armenian side was associated with the famous Serbian actor Milos Bikovic. On September 29, the Turkish website derindusunce.org posted on Twitter a photo of Milos Bikovich with the caption:

“Serbian mercenary Alex Djuric spotted in Armenia … Wagner is not far away.”

The tweet was later deleted, but the screenshot remains.

The photo is actually taken from a film – this is a shot from the tape of the warfilm “Kosare”.

The actor himself replied to the Turkish outlet on Twitter:

U pauzama snimanja Juznog, reklame i predstave u BDP, ja tako, ponekad, obučem uniformu i odem da uspostavim mir tamo gde je to potrebno.

?— Biković (@Bikovic) September 29, 2020

Also, the Azerbaijani and Turkish press actively disseminated messages about Syrian militants’ participation from the Armenian side. On October 1, many Turkish and Azerbaijani publications simultaneously posted and printed materials under the stereotypical headline: “Syrian Terrorists as part of the Armenian Occupation Forces.”

To support their claim, they used photographs, allegedly circulating on Armenian social networks – again without any references or links.

In fact, the photo above shows an Armenian detachment in Rojava, Syria. It was formed in 2019 to protect the Armenian population from Islamist terrorist groups. This was reported on in the Arabic press.

The studies prepared by the authors from Baku and Yerevan use the terminology and toponymy chosen by the authors. Terms, place names, opinions and publication ideas do not necessarily coincide with the opinions and ideas of the project, its donors, JAMnews or its individual employees