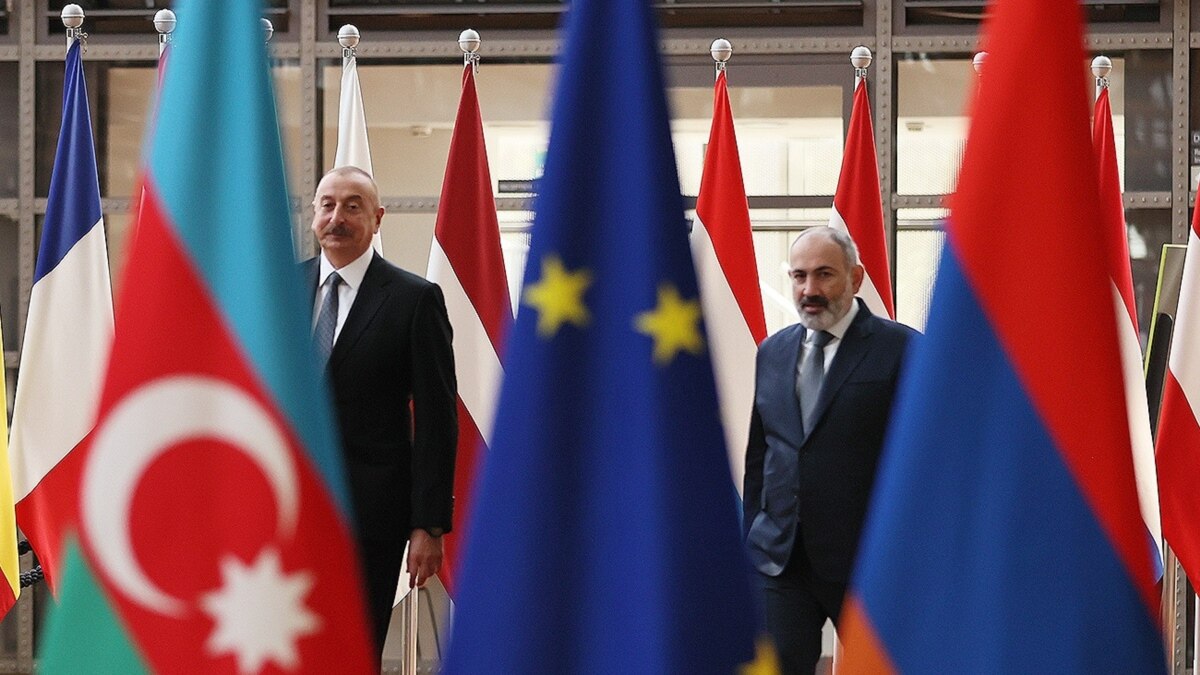

“Media law” in Azerbaijan: will it become even more difficult to talk about Karabakh?

The new Azerbaijani law “On Media” was perceived by independent journalists as an attempt to finally deprive them of their voice. But how will it affect the coverage of the Karabakh conflict, which had already been complex and unsafe before the law was passed?

The Azerbaijani government reserves the right to fully control the media sphere, as follows from the new Media Law, which will come into force after the President signs it.

It is planned to create a register of journalists and media structures and issue licenses for journalistic activities. Many local and international experts consider this legislation a from of censorship and predict that the law will further restrict freedom of speech in the country.

Ayten Farhadova, journalist:

“The new law is a trap for independent journalists, and, first of all, for those who cover the conflict.

It has always been a difficult and dangerous area and the difficulties were created not only directly by the authorities. For example, in 2016 I interviewed a family of a guy who was illegally drafted into the army (he was objectively not fit for military service). He was sent to the frontline and died there.

During the same period in Armenia, soldiers’ mothers protested against deaths on the front line. During the interview, I asked the mother of this deceased guy if she wanted to make some kind of anti-war appeal and the entire household immediately attacked me. They began to ask who sent me, they told me not to write anything about them. In their eyes, I was a provocateur.

And now, after the adoption of a new law that will make the activities of independent journalists illegal (because no one will give us a license, that much is clear), any such conflict can result in detention of a journalist.

In general, if until now, while covering the conflict, independent journalists and the media were walking on thin ice, now this ice has become even thinner, and the situation is even more powerless.

In addition, according to my feelings, after the war, there were much fewer journalists writing on this topic. And even fewer are those who voice thoughts that differ from the official position of the state.

In general, after the war the situation changed a lot. This is no longer the conflict we are used to, and to cover it now requires a completely new format, but no one has figured out which one yet.

Huseyn Ismailbayli, editor of the regional project:

“At the moment, the most insurmountable problem facing independent journalists covering the conflict is traveling to the liberated territories.

We have almost no chance of getting there. Officially, passage for “mere mortals” is prohibited due to the fact that these territories are still mined. The trips are organized exclusively by the authorities, who take only journalists from pro-government media outlets.

The new law will not aggravate this situation, because there is no way to aggravate it any more.

Difficulties may arise with the collection of information from official sources. But, again, these problems have existed before. For example, requests sent by independent journalists to various structures were almost always ignored before, and now, perhaps, they will contunue to do so “legally”.

Without getting into the register, independent journalists, in fact, will turn into ordinary citizens, without any journalistic rights and advantages.

Today, it is hardly possible to conduct polls on the Karabakh issue on the streets.

But for those who are engaged in analytics at home in front of a computer, the new law will not change anything at all.

I do not think that independent journalists covering the conflict will be afraid to write something that contradicts the official position of the authorities on this issue.

In my editorial practice, I am faced with a rather a different problem – journalists themselves are sometimes simply not able to look at things objectively because of the comprehensive state propaganda”.

Asaf Guliyev, journalist:

“There is nothing new in this new law, since it simply legitimizes a long-standing situation.

It is much worse that in Azerbaijan there are very few journalists who specialize in the topic of the conflict and are well versed in it.

Of course, this is a very complex topic. The truth is not to the liking of either society or official structures. Most of those who write about the conflict focus on the image of the enemy. The objective reflection of events fades into the background. This requires access to alternative sources of information, and Azerbaijani journalists have very limited access to them.

As far as I know, not a single Azerbaijani media, except for those funded from abroad, has sources of information in Armenia or among the Karabakh Armenians, because official circles don’t want it.

It is sad that even now, after the war, the old stereotypes dominate in Azerbaijani journalism.

There is a small group of outcasts calling for peace, but they are not competent enough and their calls are not sufficiently substantiated.

The voices of those who are well versed in the conflict and support the idea of peace are lost in the opinion of the overwhelming majority.

Both Armenia and Azerbaijan need peace today more than ever. However, due to the dominance of superficial and distorted information, this word itself causes aggression in society.

This perception can be changed only by changing the information environment. But this should be done by the governments of both countries”.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union