Is Saakashvili a political prisoner? Lawyers and human rights defenders' explain

Is Georgia’s ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili a political prisoner?

On November 9, the influential international human rights organization Amnesty International reacted to the arrest of former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili on Twitter, referring to it as a “political revenge” and “selective justice.”

#Georgia: ex-President #Saakashvili (5th week of hunger strike) violently transferred to prison hospital; allegedly threatened; denied dignity, privacy & adequate healthcare. Not just selective justice but apparent political revenge.

— Amnesty International (@amnesty) November 9, 2021

“Former President Saakashvili (in his fifth week of hunger strike) was forcibly taken to a prison hospital; there are reports that he has been threatened, his dignity, personal space and [right to] adequate medical care have been violated. This is not just selective justice, it is obvious political revenge”.

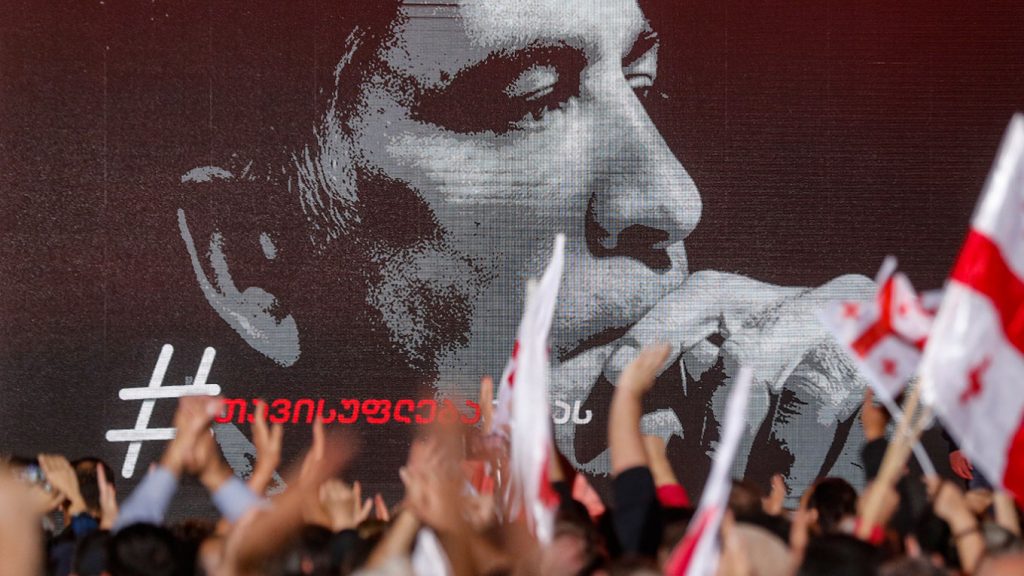

Since the day of Saakashvili’s arrest, public opinion has been divided on whether Saakashvili can be considered a political prisoner? Some say that the country’s third president is, indeed, a political prisoner while others believe that Saakashvili committed crimes for which he should be held accountable, and therefore his arrest is a legal issue, not a political one.

What does “political prisoner” mean? Who and by what criteria is considered a victim of political revenge? Where is the line between legal responsibility for a specific crime and political persecution? And can the events that took place around Mikhail Saakashvili on November 8 be considered a political persecution – namely his forcible transfer to the prison hospital in Gldani, where, according to the Public Defender, the conditions that were created for him that humiliate his dignity.

When can a person be considered a political prisoner?

The term “political prisoner” usually refers to a person arrested for their political activities – someone who fights against or criticizes the government. However, there is no specific, universal and clearly defined definition of the “political prisoner”, and all lawyers agree with this.

- Mikheil Saakashvili’s transfer to Gldani prison: November 8 chronology

- Saakashvili’s hunger strike almost hit a month – what do we know about his health and what future awaits him?

- MEP Von Cramon: Georgia’s ruling party has never been further away from EU membership

Moreover, the term “political prisoner” does not appear in most international law documents or in national laws of countries.

The term “political prisoner” is also absent from all human rights documents – the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, the Protocols to the Covenant or the Convention, nor in the rules of the European Court of Human Rights.

How does law determine who can be considered a political prisoner?

On October 3, 2012, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe became the first major intergovernmental organization to approve specific criteria for defining a “political prisoner”.

Every lawyer, speaking on this topic, first of all mentions the resolution 1900 of the Council of Europe.

Resolution 1900, which was also signed by Georgia, addresses five cases when a person can be considered a political prisoner. Those include the following cases:

➊ If the arrest violates the fundamental rights enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights – freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of speech and information, freedom of assembly and association;

As Merab Kartvelishvili, director of the human rights program of the Georgian Young Lawyers Association, explains, if a person is arrested for carrying out certain activities.

➋ If the arrest was made solely for political reasons and the crime was not committed;

➌ If detention as a measure is clearly incommensurate with the crime for which the person is charged or convicted, and the decision to arrest them is politically motivated;

For example, if a person committed a crime for which they were supposed to be sentenced to five years, but were sentenced to ten years for political reasons instead.

➍ If the arrest and detention of a person is inconsistent with other similar cases and is discriminatory;

Cases in which other persons are not arrested for a crime, and the person in question is imprisoned because of a political motive.

➎ If the arrest and detention of a person is inconsistent with other similar cases and is discriminatory;

This means that the person in question could not exercise their right to a fair trial because they were involved in politics and the court was politically motivated in its decisions.

“The Council of Europe says that if political motives are higher than interest in the administration of justice, a person can be considered a political prisoner”, says Merab Kartvelishvili.

At the same time, the Council of Europe clarifies that a person who is considered a political prisoner does not have to meet all five criteria:

“These are not cumulative reasons. That is, not all of these cases must be met. One of them is enough for a person to be considered a political prisoner”, says Nana Mchedlidze, an expert on international law and a human rights’ lawyer in Georgia.

In addition to this regulation, the term “political prisoner” is used in accordance with criteria recognized by various influential and reputable international organizations.

One such international organization is Amnesty International. An influential human rights organization also recognizes and defines the term “political prisoner”.

There is a difference between the criteria of the Council of Europe and Amnesty International: Amnesty International uses the term “political prisoner” in a broader sense than the Council of Europe resolution and seeks to cover all cases in which a political element is visible.

“A political prisoner is any prisoner in whose case there is a political element, be it the motivation for the prisoner’s action, the action itself or the motivation of the government”, says Amnesty International.

The Council of Europe criteria are stricter.

“It will be very difficult to apply the criteria of the Council of Europe to many people, especially to people who are not related to politics. Amnesty International has a broader definition and within which, not only a politician or a former high-ranking official fall, but also ordinary people and activists who are persecuted because they have different views and opinions”, explains Merab Kartvelishvili.

Another legal act that people who consider themselves political prisoners rely on is the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. The term “political prisoner” does not appear directly in this Convention, although it sets out the scope of the limitation of rights in accordance with the Convention.

That is, this article states that the restriction of fundamental human rights by the state can be carried out for purposes permitted only by the Convention.

In other words, any limitation of state-guaranteed human rights must be clearly justified and formulated and should not raise suspicions that this is persecution and discrimination against a person for political or other reasons.

Mikheil Saakashvili, who is now filing a lawsuit with the Strasbourg Court, points out that Article 18 is among the articles that have been violated in his case.

-

Criminal cases against Mikhail Saakashvili

Mikhail Saakashvili was detained on October 1, 2021. Four criminal cases were launched against him in Georgia.

He was convicted in two of them (orchestrating the beating of deputy Valery Gelashvili and pardoning the killers of Sandro Girgvliani) and sentenced to 6 years in prison. He was charged in two cases, and these cases are now being considered by the court.

Case # 1 – The case of the beating of Valery Gelashvili – Mikheil Saakashvili was accused of organizing a group attack on MP Gelashvili. Gelashvili was attacked in 2005. The attack was preceded by an interview with Gelashvili to the newspaper Rezonansi, in which he spoke offensively about Saakashvili and his wife. The investigation claims that Gelashvili was beaten at Saakashvili’s order.

Case # 2 – The case of the murder of a bank employee Sandro Girgvliani in 2005 is one of the most high-profile cases in the modern history of Georgia. The ex-president was accused not of the murder of Girgvliani, but of pardoning the murderers by prior agreement. For this he was sentenced to three years in prison. Saakashvili pardoned Girgvliani’s killers in 2008, cutting their sentences in half.

Case # 3 – November 7 – The ex-president is accused of dispersing the participants of the anti-government protests in November 2007, as well as the persecution of the Imedi TV channel. According to the prosecutor’s office, in connection with the events of that period, the TV channel suffered damage in the amount of more than 3 million lari (more than 2 million dollars). The punishment for these crimes is imprisonment for a term of 5-8 years.

Case # 4 – embezzlement of state property, the so-called. The “jacket case” is a case of misappropriation of more than 9 million lari (approx. $ 5 million) from the budget for personal needs (including the cost of luxury hotels and sanatoriums, visits to beauty clinics and clothing, including the purchase of seven jackets in the UK). The punishment for this crime is from 7-11 years in prison.

These four cases were brought against Mikheil Saakashvili after he left office in 2014. He was convicted in the first two cases in 2018 and sentenced in absentia.

After Saakashvili’s arrival in Georgia at the end of September 2021 and his arrest, the prosecutor’s office launched another case against Mikheil Saakashvili.

Case # 5 – Illegal Border Crossing Case – On October 1, 2021, the General Prosecutor’s Office announced that the Ministry of Internal Affairs is also investigating Saakashvili’s illegal border crossing, which provides for a maximum sentence of 5 years in prison.

Who grants a person the status of a political prisoner?

Lawyers say that “political prisoner” is more a political term than a legal one.

The Strasbourg court never explicitly states that a person is a political prisoner. This is not part of its mandate. Strasbourg examines whether Article 18 has been violated – why human rights have been restricted and whether this restriction is due to some hidden purpose not provided for in the Convention.

At the same time, a violation of Article 18 of the Convention does not necessarily render the person deprived of his liberty a political prisoner.

However, it clearly indicates that the deprivation of liberty served “another unspoken purpose”. If it is found that this “hidden purpose” violates the fundamental guarantees of the European Convention on Human Rights, namely freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of expression, information, assembly and association, then the decision of the European Court of Human Rights on violation of Article 18 Conventions tend to be a pretty strong argument for a prisoner to be considered “political.”

Nana Mchedlidze gives specific examples when the Strasbourg court found a violation of Article 18:

The 2018 Strasbourg Grand Chamber ruling in the case of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, Navalny v. Russia, does not state that Navalny is a political prisoner, but states that the detention measures against him were an attempt to suppress political pluralism.

“Russia’s actions have been described as suppressing the main criterion for effective political democracy – political pluralism. That is, they gave a tougher assessment of Russia’s actions”, ways Nana Mchedlidze.

She gives another example – the case of Rasul Jafarov v. Azerbaijan:

The Strasbourg court did not refer to Jafarov as a political prisoner, but said that he was arrested for his political activism. (By the way, the Azerbaijani authorities released Jafarov on the same day, as soon as the European Court announced this decision – JAMnews).

Guram Imnadze, director of the Justice and Democracy program at the Center for Social Justice (EMC), says that “as a rule, the status of a political prisoner is given to a person not by a legal, but by a political body”.

Imnadze recalls the case of 2012, when after the change of power, the Georgian parliament adopted a special act and massively granted the status of political prisoners to 170 persons. (This status has not been granted to them by any international organization, and has also been criticized by local civil society organizations – JAMnews)

“Although there is also Resolution 1900 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe and a determination from Amnesty International, it is still difficult to legally assess whether a person is a political prisoner”, says Merab Kartvelishvili:

“We say that the political motive should prevail, but how to draw the line – what prevails and how? This is not an easy answer, and it is often very difficult for citizens to understand when, for example, lawyers say that someone is guilty but is a political prisoner. People get confused”.

Is Mikheil Saakashvili a political prisoner?

At this stage, some human rights organizations working in Georgia do not assess whether Mikheil Saakashvili is a political prisoner. They say they follow the progress of the case.

“If we want to conduct a legal analysis and see a legal result, we need to wait for the decision of Strasbourg. The Association of Young Lawyers of Georgia has so far refrained from assessments. We are observing how this will proceed”, says Merab Kartvelishvili.

However, most of them openly state that the former president is a political prisoner, and several criteria indicate this. Among them, the most obvious is that Saakashvili found himself in a discriminatory situation, and a violation of the right to a fair trial.

According to Aleko Tskitishvili, executive director of the Human Rights Center, the discriminatory treatment of Mikheil Saakashvili manifests itself in the government’s stubborn refusal to transfer him to a multidisciplinary clinic, despite the fact that that there is a clear need for this, and many prisoners use this opportunity:

“When there are no conditions in the penitentiary system in which a prisoner can be treated, he is usually transferred to a multidisciplinary clinic without any problems. When Mikheil Saakashvili is denied, especially when there is a doctor’s recommendation and a request from international organizations, and he is persistently sent to a prison hospital where there are no conditions, one can assume that the president is in a truly discriminatory situation and he is a political prisoner”.

Eduard Marikashvili, chairman of the Georgian Democratic Initiative (GDI), says that when the government uses certain issues as additional punishment besides the criminal case, it says a lot about the authorities’ motives:

“In this case, refusing to transfer, or transferring him to a place where he could have been subjected to psychological pressure from prisoners, may not be essential for solving criminal cases, but in the context of assessing the whole picture, this tells us that the government has very a big dose of political revenge”.

Many organizations and human rights activists talk about the violation of the right to a fair trial against Mikheil Saakashvili.

This was announced on October 12 by six influential organizations operating in Georgia. In this statement, the organizations openly stated that “politically motivated justice is being carried out against Mikheil Saakashvili”.

The Georgian Democratic Initiative (GDI) wrote about the unfair trial of Mikheil Saakashvili back in 2015 in its report Politically Motivated Justice in Georgia.

The document says that there is not enough evidence in these cases, and they are based on the testimony of politically motivated and interested persons (former Defense Minister Okruashvili, former Speaker of the Burjanadze Parliament), and also have signs of selective justice (in the so-called “jacket case”).

“The materials of the case, which we then studied, allow us to conclude that there was no evidence for bringing charges against him, let alone a conviction. Obviously, this does not mean unequivocal innocence, this is an assessment of the cases themselves, after reading which one gets the feeling that justice is unfair and has a political context”, says Eduard Marikashvili.

The affairs of Mikheil Saakashvili also raise many questions from Aleko Tskitishvili. Especially the so-called “jacket business”. Tskitishvili’s organization is now monitoring cases in which Saakashvili has not yet been convicted.

He says that the Center for Human Rights and other organizations at one time did point to the advisability of using state funds for Saakashvili, although, according to him, the current president, Salome Zurabishvili, is not modest and her spending of state funds is also questionable. For example, 2 million lari, which the president spent on the purchase of antique furniture for the residence on st. Atoneli.

According to Tskitishvili, in the conditions of independent investigative bodies and impartial justice, this acquisition of Salome Zurabishvili could also become the subject of interest of the investigating authorities:

“When one president is accused of buying jackets, and the other president is not even asked why she is buying candles and luxury goods, it is already clear that we are dealing with a discriminatory attitude and political motives”.

The case for pardoning the accused in the murder of Sandro Girgvliani is also political for the lawyer Georgy Mshvenieradze. (As a reminder, the president was convicted of pardoning the murderers of Girgvliani). According to him, pardon is the exclusive right of the president and assessment of the content of the pardon is inadmissible.

“In case of dissatisfaction in society, the person who gives the pardon bears political responsibility at the expense of his own political career and rating. Due to the nature of the pardon, it is unacceptable to consider the content of the act of pardon through judicial control and give it a criminal assessment”, said Giorgi Mshvenieradze.

According to lawyers and human rights activists, another sign that Mikhail Saakashvili’s imprisonment is political are statements by high-ranking officials.

Statements of political persecution by government officials

“If he does not behave decently, we will add more articles to him”, Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili said two days after Saakashvili’s arrest.

Special attention of experts was focused on the statements about the hunger strike of the former president.

“The whole prison laughs at the fact that this man drinks three litres of lemonade a day”, said Irakli Kobakhidze, chairman of the ruling party.

“We have all heard that a person can live for 40 days without food, and we are waiting for the 41 day”, one of the leaders of the party Mamuka Mdinaradze said about the hunger strike and the state of health of the ex-president.

“Millions of people around the world are starving because of poverty. It doesn’t bother me at all”, said Minister of Economy Natia Turnava when journalists asked her about Mikheil Saakashvili’s hunger strike.

“When they say that if he leaves politics, he will not be punished, that is, it turns out that a person is responsible for something, because he has not left politics. These assessments leave no room for controversy [whether Saakashvili is a political prisoner]”, said Giorgi Mshvenieradze.

“If these applications get to Strasbourg, the court will definitely consider them”, says Merab Kartvelishvili.

“The fact is that this whole campaign serves to humiliate Saakashvili, insult him. This is political persecution”, says political observer Gia Khukhashvili.

If Saakashvili is a political prisoner, is he innocent?

The lawyers who spoke with JAMnews have an unequivocal answer to this question – a person can commit a specific crime and still be a political prisoner. That is, being a political prisoner does imply innocence, and recognition of someone as a political prisoner does not exempt a person from criminal liability.

“Recognizing someone as a political prisoner does not mean that we have a moral right to demand his or her immediate and unconditional release, but we have the right to demand a fair trial”, says a 2012 handbook of Georgian lawyers and human rights defenders about political prisoners Georgia.

According to lawyers, the main thing in this case is a fair trial.

“It is very important that the judicial process in such cases was especially transparent, the principles and standards of a fair trial were especially high”, Guram Imnadze said.

The non-governmental sector operating in Georgia, speaking about the cases of Mikhail Saakashvili, first of all questions the right to a fair trial.

“Given that the judicial system is characterized by clan management, loyalty to the government and the administration of defective justice, as well as disastrously low trust in this institution, the possibility of Mikhail Saakashvili’s right to a fair trial is questioned”, the statement said.