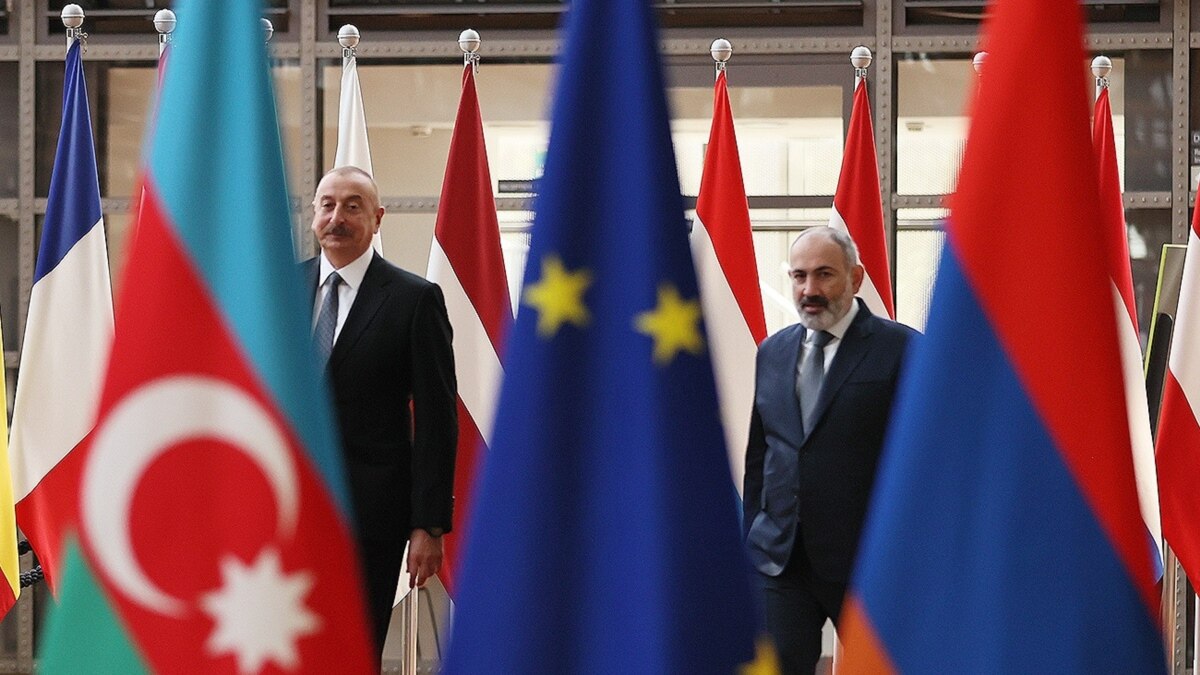

"If the alternative to war was peace, I would choose it"

A walk in London’s Chelsea district leads Leila to an Armenian church, and the girl decides to photograph it to share it with her new acquaintances from a closed Facebook group where Azerbaijanis and Armenians discuss “cinema, wine and dominoes”, trying very hard to avoid sensitive topics and conflicts.

Leila, 33, has been living in the UK for two years now. But although the 2020 Karabakh war took place thousands of kilometers from London, it did not make it any less painful.

“It seemed to me that from a distance I felt it more than if I were in Baku. I could not think about anything else despite the fact that the war did not affect my family or my friends. In London, I live alone, and in the quarantine conditions there were not many options for distraction. The first couple of weeks I could not work normally, because I was on the phone all the time: news, instant messengers, Telegram. It got to the point where I had to sign up for sessions with a psychotherapist, because I felt very anxious.

I had mixed feelings. On the one hand, I was horrified, realizing that war is evil, humanity has not invented anything worse. But, on the other hand, although I didn’t support this war, but to some extent justified it. By virtue of my profession [business project analyst – ed.], I know that when evaluating any project, it is extremely important to correctly identify the alternative scenario. So, if the alternative to this war were peace, then I would not hesitate to choose it. But the negotiations had come to a standstill for many years, and I saw that the alternative in this case was a sluggish “truce” that lasted for decades and led to death, hatred and increasing alienation. I’m not sure it was much better than the war.

I am a member of the Facebook group of Azerbaijanis living in the UK, and its members, as a private initiative, collected money to help the families of the dead and disabled. In principle, they still do it by organizing something like a monthly subscription.

It was a shame that I did not receive any moral support from my foreign friends and colleagues. No, I didn’t expect them to support one of the sides. Moreover, I believe that in such complex conflicts, it is better for an intelligent person from outside to do this. I heard words of support and concern for my loved ones in Baku from just a few people. Well, a couple more people reacted when I wrote in plain text on social media that I was not well.

I thrashed between all kinds of emotions. I cried when I saw a video in which the flag of Azerbaijan was raised in Sugovushan (at that time Madagis); waited impatiently for the ministers to leave the ten-hour talks; she sobbed when they bombed Ganja and Barda, could not believe my eyes and ears when they took Shusha; rejoiced when they signed a peace agreement.

I must also say that I have a special attitude towards Karabakh. My grandfather had roots from Lachin, and part of my family is internally displaced persons from Aghdam, before the war they had a house there with a beautiful garden, from which now nothing remains. Of course, I would like to visit Aghdam, although I understand that it will not be possible for a very long time.

It so happened that I have never met Armenians in my life and did not communicate with them on the Internet. But I accepted the invitation ofmy former colleague to join the group created to establish ties between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. This group provides an opportunity to break stereotypes. I am absolutely not characterized by nationalism or hatred of an entire nation, but during the information war in September-November 2020, when swearing and mutual accusations were spreading from everywhere on social media and Armenians were all too often stubborn nationalists you don’t want to start generalizing and thinking, that they are all like that. This group is a great opportunity to see that no, not everyone is, indeed, like that.

The group allows you to communicate with people in a cultural and civilized manner, even in spite of radically different views on some issues and stop dehumanizing and demonizing Armenians, seeing them as ordinary people, with the same feelings and experiences. I think now that the war is over, we all have a long and painstaking process ahead of us. It should take place not only at the official level. We, ordinary citizens, can also take some steps towards peace”.

In the comments under the photo of the church, Armenians and Azerbaijanis exchange jokes that they only understand Albanian churches and primordial Armenian lands, sneering at the common stereotypes that the governments and societies of both countries use in the information war – and this gives reason, if not for optimism, then for hope.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union