How life has changed in Azerbaijan after the second Karabakh war. Photos

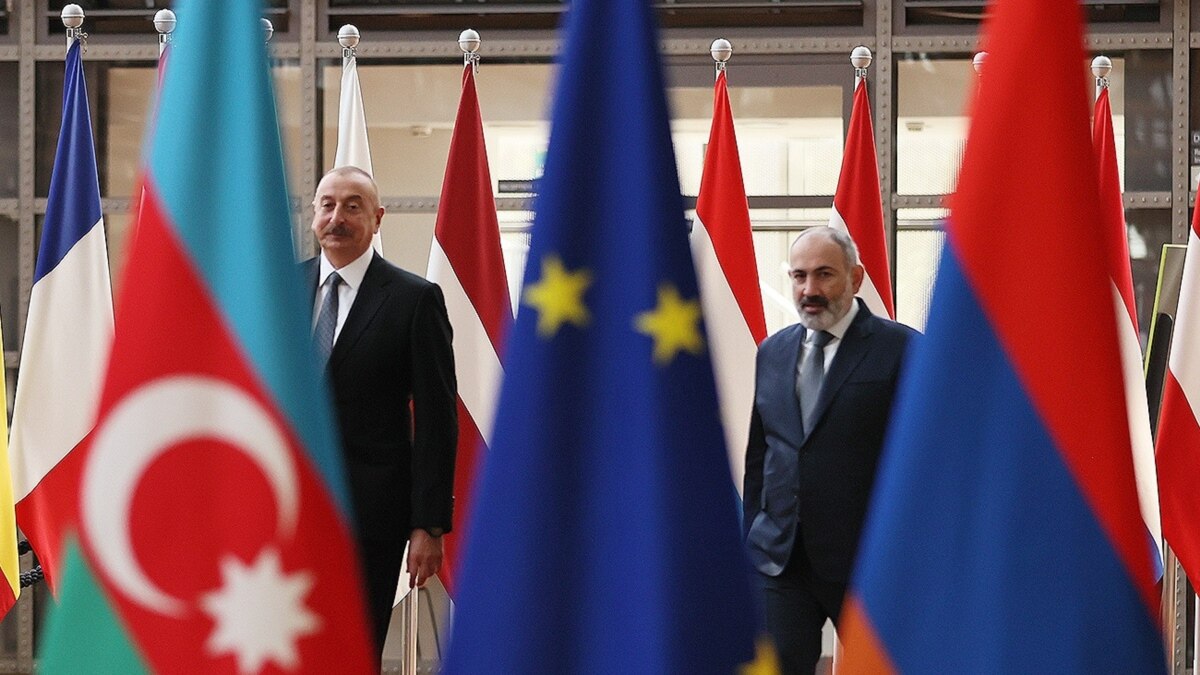

The loss of Karabakh and the desire for revenge have been a unifying idea for the Azerbaijani people for almost thirty years. Lost areas were listed on the first page of school diaries, signs on the roads led to them, and the news every morning greeted us with the usual “the enemy violated the ceasefire so many times”. All this was an integral part of everyday life. What has changed in Azerbaijan after the second Karabakh war?

A new reality has been created. Where there used to be mourning for civilian and lost lands, a vacuum has formed, and a new idea is quickly beginning to fill it: victory and revenge.

Judging by the strength and emotional richness of the message emanating from the authorities and readily accepted by society, this new idea is conceived as equivalent to the previous one, and it should fulfil the same function – to unite a nation that is rather fragmented when everything is calm.

While the page with the list of war defeats in school diaries has not yet been replaced with the list of victories (and this is only a matter of time), here are some examples of how the results of this war are perpetuated in Azerbaijan.

Victory lends itself better to commercialization than defeat. Previously, small businesses could only use place names as a name. Now they can play with the theme more freely.

For example, the store “KhanCandy”. The name hints at the main city of Karabakh, which the Azerbaijanis call Khankendi, and the Armenians call Stepanakert.

Another cafe also turned into “KhanCandy”, and as a result of some forced rebranding. The director of the Anderson cafe chain, a citizen of Russia, supported Armenia on social media. Anderson’s Baku branch immediately abandoned the franchise and is now called KhanCandy, although (as of May 2021) it has not changed either the interior or the menu.

This is a photo of a local “victory-flavoured” energy drink

Several months have passed since the end of the war, but the running line “Karabakh is Azerbaijani!” is still on displays of the sides of buses, although a description of the bus route would be more useful.

The political idea changed from sacrificial to victorious, and the focus shifted from dead civilians to dead soldiers. Periodically, this is not even related to the war. For example, when it comes to feminists, they are reminded that they were against the war – even though what they are talking about has nothing to do with it.

Previously, most of the society condemned “dishonest” fights, when several people attack one person at once. But now the news about the “punishment” of the man who joked about the soldier who died at the front is received with approval.

These are temporary phenomena, but some new names and titles are more permanent.

The new metro station is named November 8. This date is officially recognized as the Day of Victory in the second Karabakh war.

The station itself was built a long time ago, but the name was given to it recently.

Also, Nobel Avenue was renamed November 8th Avenue.

There is also a project of building a mosque in Shusha, the main building of which will be in the form of the number 8, and the minarets – the number 11, also in honour of the same date.

The most prominent of the victory monuments the infamous War Trophy Park. There is no demonstration of the military might of the Azerbaijani army in it and any hints of the horrors of war are completely neutralized by caricatured dolls of Armenian soldiers and T-shirts with “trendy” quotes such as “What happened, Pashinyan?” or “We chased them off like dogs.” These are phrases from speeches made by Ilham Aliyev during the war. Apparently, this museum simply complements the picture of victory with the image of a weak and cowardly enemy.

Trajectories is a media project that tells stories of people whose lives have been impacted by conflicts in the South Caucasus. We work with authors and editors from across the South Caucasus and do not support any one side in any conflict. The publications on this page are solely the responsibility of the authors. In the majority of cases, toponyms are those used in the author’s society. The project is implemented by GoGroup Media and International Alert and is funded by the European Union